In the Thick of It

A blog on the U.S.-Russia relationshipRussia’s Pivot Away From West to China Explained by More Than Ukraine Crisis

As relations between the West and Russia went from bad to worse in the wake of the Ukraine crisis, one consequence has been Moscow’s decision to strengthen ties with China, while devoting less energy to attempts at cooperation with the U.S. and EU.

Relations between Russia and China have become so close that some policy influentials on both sides have begun to advocate a military-political union between their two countries. (See the summaries of two recent Russian press reports below.)

However, while the post-Cold War Sino-Russian rapprochement has definitely accelerated since the Ukraine crisis, one should bear in mind that Russia’s “pivot” from West to East is a longer-term trend in terms of bilateral trade opportunities and public opinion.

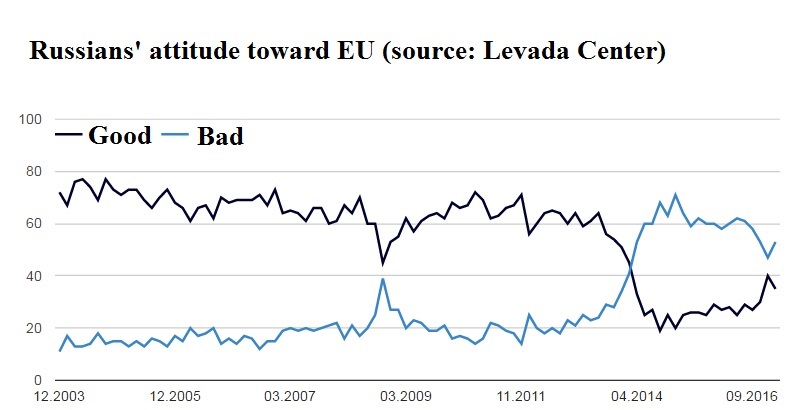

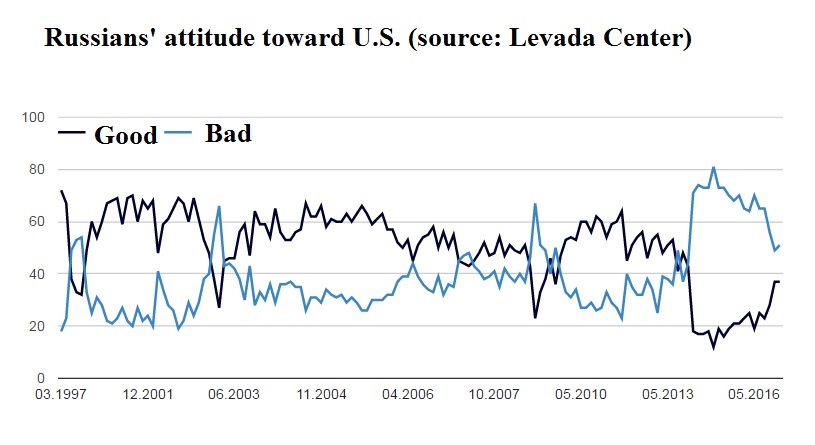

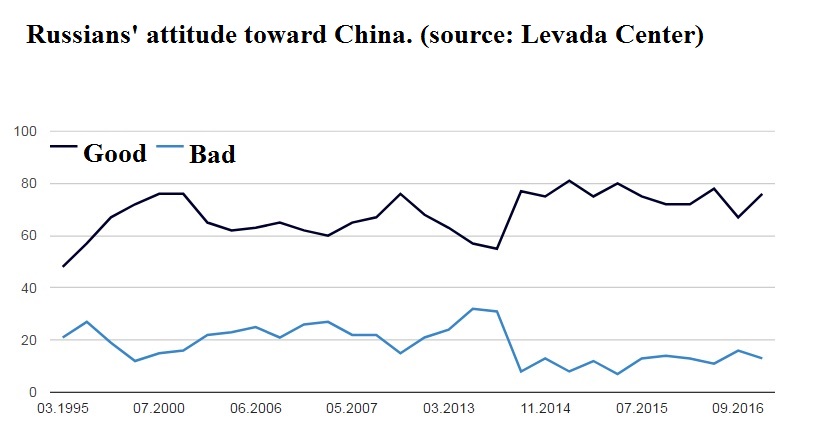

On the latter point, take a look at these polls conducted by Russia’s most prominent independent pollster, the Levada Center:

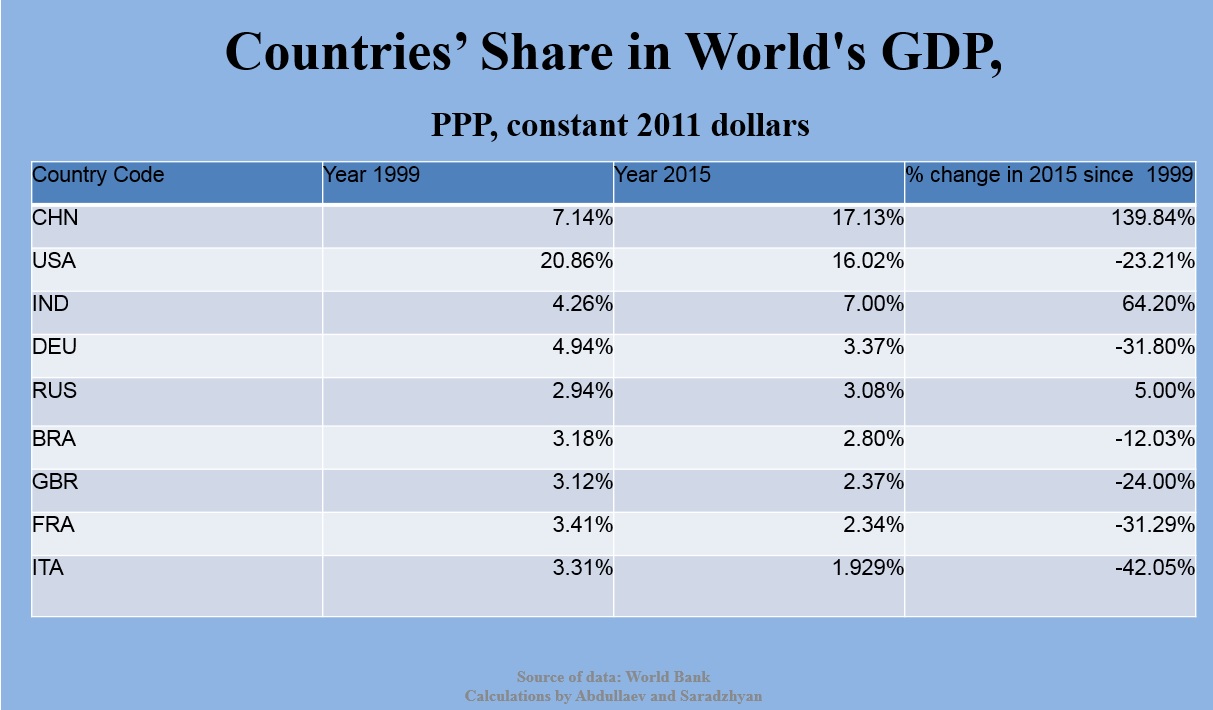

There’s a good chance these longer-term trends in Russians’ attitudes toward the West and East (and some of the policies that accompany them) are driven not only by the animosities between Moscow and Washington/Brussels—now over Ukraine, earlier over Yugoslavia and other crises—but also by the fact that China has been expanding economically at rates that the leading Western powers can’t keep up with. Look at this table:

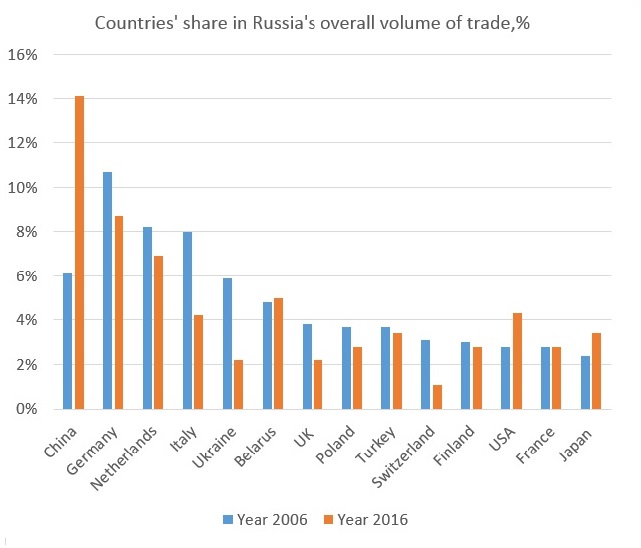

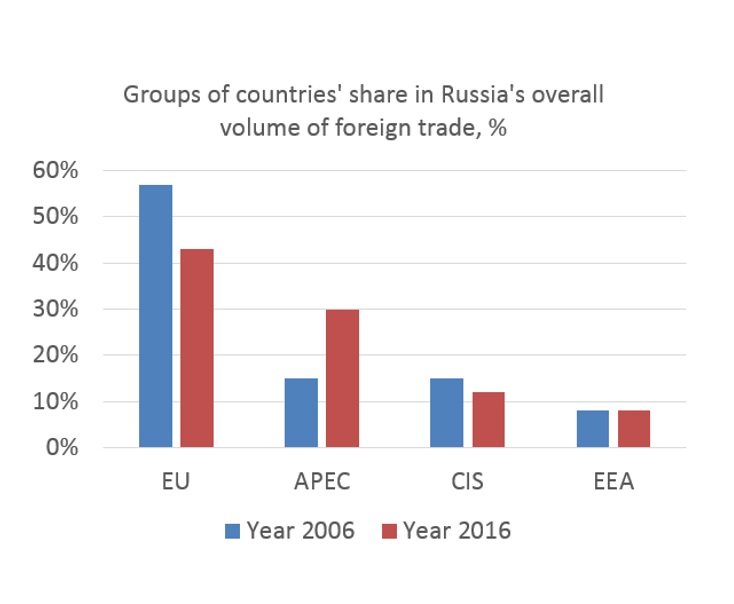

Simply put, Chinese growth has generated more trade opportunities for the Russian economy. China’s share in Russia’s trade has expanded, while EU and U.S. shares have shrunk. Given these economic trends, even if the U.S. and EU were to mend relations with Russia tomorrow, Russia’s pivot to China will continue as long as the latter keeps rising.

And here are those summaries of recent Russian media publications on the prospects of a Russian-Chinese alliance:

“Russia and China Have Been Offered Hands, Backs and Sides,” Kommersant, 04.04.17

Russian and Chinese experts met in Moscow on April 4 for two days of discussions under the aegis of the Valdai Club.

Russian participants actively lobbied the idea of uniting Russia and China against the unipolar order. Sergei Karaganov suggested that the fight against Western influence should be initiated by the event’s participants.

Karaganov’s proposal won support of the chief researcher of the Xinhua Center for World Affairs Studies, Sheng Shiliang. The Chinese researcher cited Mao’s observation that “the essence of American imperialism cannot change” and proposed a three-pronged strategy for development of Chinese-Russian relations: back to back against external challenges, side by side against Trumpism and hand in hand for economic cooperation.

Most Chinese guests, however, opposed confrontation with Washington. Fudan University professor Fan Yuitsyun said such a confrontation was not in the interests of the U.S. or Russia or China. "This is obsolete geopolitics; the world is now busy solving other problems: how to preserve globalization, what to do with climate change. In 2017, even economic cooperation can be neither bilateral nor directed against a third party. The key thing is building chains of added value in the world.” The professor said China, the U.S. and Russia should explore which problems these three countries can work on together. Among these he named North Korea’s nuclear program, counter-terrorism and arms reduction. Discussion of the possibility of a Russian-Chinese military alliance generated differences. Many Russian participants came out in support of this idea, but Sheng Shiliang decisively rejected it: “There were already three unions between us. We were married three times and we divorced three times. Where is your conscience?” However, the director of the Center for Russian Studies at the East China Normal University, Feng Shaolai, countered that "after 60 years chemical processes begin in the human body that allow us to experience love again.”

Q: What role does Russia play in China's foreign policy?

A: Russia and China are not formal allies, but in recent years much has been done to improve relations between them.

Q: You are one of the few in China who openly advocate the formation of a full-fledged Russian-Chinese alliance. Why do you think that it is important?

A: From my point of view, both Russia and China are under pressure from the United States. Unfortunately, there is no alliance between us. As I understand, neither side is ready for this. And that's why we can neither give each other adequate support nor improve our relations further. Our cooperation has boundaries.

Q: Why, in your opinion, does China remain committed to the policy of non-entry into alliances?

A: This principle was adopted only in 2008 in order to maintain an equal distance from the two superpowers, Russia and the U.S., without offending either of them. At that moment, it met our interests, but times have changed, and now China has half approached the status of a superpower. Therefore, this principle no longer meets our interests. I do not understand why Russia does not insist on forming an alliance with China.

Q: China quite clearly stated that it is not in its interests to pursue such an alliance, and in this situation would Russia not look stupid if it insisted?

A: But if Russia insisted, then it would be a problem for China rather than a problem for the two sides as it is now. Last year, during the visit of Vladimir Putin to China in September, Russia and China for some reason signed a statement saying there was no union between them. This step remains unclear to me.

Q: Usually it is said that Russia and China have their own unique set of problems and it is not in the interests of Russia, for example, to protect China on the issue of the South China Sea. Similarly, it is not in China's interests to defend Russia's actions in Crimea and Ukraine.

A: Yes, we do not support each other openly on these issues, and this establishes an artificial ceiling for our relations: They have nowhere to develop.

Q: When I discuss this issue with Chinese scholars, they usually say that we already had an alliance in the 1950s and it ended badly because in an alliance one side always dominates, and the other side obeys.

A: I know this argument. If we look at history, no alliance lasts forever. Any union ends. I do not think that this is a good argument. It's like saying to a divorced person: Do not marry again because nothing good came of your first marriage.

Q: You said that any union has a purpose. Back then we stood together against the world of capitalism. What would be the goal of the Russian-Chinese union now?

A: The goal is to increase the political power of our states, to protect our territory and to reduce the military threat from the United States. China has a territorial dispute with Japan, which has U.S. support. Russia has a territorial dispute with Ukraine, which has U.S. support. We have a similar source of threat.

Q: Many Russian researchers note that the joint initiatives of Russia and China, such as the SCO and BRICS, have not produced the result that the parties expected. China has created a new four-way mechanism instead of the SCO in Central Asia, and the BRICS summits leave an impression that all five countries talk about their own problems and do not hear each other. Why do you think that is?

A: As for the SCO, its status was undermined by Russia. It began as the "Shanghai Five," which dealt with preventive security issues, preventing conflicts between members. Fortunately, it became possible to transform it, move it toward active security and cooperation, when the members jointly fought against the threats of separatism, terrorism and extremism along the perimeter of the borders and within the organization. Unfortunately, at some point, your government began actively pushing for India and Pakistan to joint. These are strategic rivals! So the SCO lost its depth, moved one level down: from active security to preventive security—now it again has to focus on preventing conflict between members.

Q: Why did China agree to this? The SCO has a consensus principle—Beijing could block the expansion, no?

A: China has resisted this for many years, but at some point this resistance in itself began to negatively impact China’s relations with Russia and India. And China decided to give in in order not to provoke conflict. But the entry of India and Pakistan seriously undermined the potential of this organization. It was effectively killed, even though it was a very promising organization! A lot of my American students wrote doctoral dissertations on the SCO 10 years ago; it looked like a new format. It could have become a real alliance! Now no one writes anything about it.

Q: And what about BRICS?

A: BRICS is a different case: It was a wrong idea from the very beginning. The member countries had no connection with each other than that Goldman Sachs analyst Jim O'Neill bundled them together and the political leadership of these countries decided to build a political association on this basis. It was doomed from the very beginning and that was evident during the summits: The countries did not have a common strategic goal, except for increasing their representation in international financial institutions. I predicted back in 2013 that BRICS was doomed to fail, and Jim O'Neill then wrote me angry letters in response. And what happened? The organization is in a coma, and Goldman Sachs’s BRICS fund was shut down in 2016. So who was right?

Q: In your opinion, did Russia's actions in the Crimea in 2014 affect the behavior of China in the South China Sea?

A: Yes, but conceptually rather than directly. That was a good example of how a country should protect its fundamental interests, but it is not entirely reasonable to compare these two situations: China did not take any islands in the South China Sea that had previously been taken by another country. Everything has long been divided between the four countries there, and no one has the opportunity to change that position without a war.

Q: But isn’t China trying to put all this sea area under its control?

A: Of course not! It's impossible. I repeat, all the islands have long been taken by Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and China. China’s share of the islands is not the largest and it has begun to strengthen them later than everyone else. And China never tried to forcefully seize the islands taken by other countries because that would require a ground war Beijing will not wage.

Q: In recent years there has been a rapprochement between Russia and Japan. Cooperation is not as wide-ranging as it is with China, but steps are being taken towards its development. Isn’t China jealous?

A: No. The foreign policy pursued by Shinzo Abe consists of two parts: to increase the level of confrontation with China and to improve relations with all the rest. Now he is trying to buy you to reduce Russian support for the Chinese policy in the East China Sea and to ensure that Russia does not agree to hold joint maneuvers with China there. And for that they are ready to pay you money.

Q: And what is so bad about the joint exercises in the region for Japan?

A: He [Abe] needs to have China look isolated on the issue of the Diaoyu Islands [Senkaku]. And he sells this proposition to his people: Look, thanks to my wise policy, no one supports China in this dispute.

Q: The victory of Donald Trump in the United States, the victory of the Brexit supporters in Britain, the growth of populism and nationalism around the world—do you see here a chain of coincidences or a pattern?

A: For the time being, we can state that the forces of economic protectionism are winning. The U.S. has led this movement, and other countries will have to follow. As for nationalism, I would not be so sure. It seems to me that the movements against the elites are winning.

Q: Is there such a movement in China?

A: Yes, although in a different form. In our case, it is an ultra-left movement. It is much stronger than it was even two years ago.

Q: Why did this wave rise right now?

A: I think that the errors of globalization and liberalism have accumulated. Globalization has two sides. The good side is the free movement of goods, services and people. The bad side is terrorism, inequality, human smuggling, pollution, diseases, etc. At some point, the shortcomings of globalization have become more visible than its virtues. As for liberalism, the U.S. has been lecturing everyone that this regime is ideal. But in its extreme form, it further strengthens the problems of globalization! And that has become obvious to people.

Q: Xi Jinping made a speech at Davos that aroused great excitement. In that speech he urged not to stop globalization. After that, many began to talk about China readiness to become a new defender of global values instead of the United States. Do you agree with this?

A: First, not everyone understood what Xi Jinping really meant. He advocated economic globalization only. China has never supported political globalization or ideological globalization or global arms control. Second, even within the framework of economic globalization, he supported only the free movement of goods and services. He did not support, for example, globalization of capital. China strictly controls the movement of capital. We learned this during the financial crises of 1997 and 2008. We controlled capital and survived. So the idea that China is ready to replace the U.S. as the flagship of globalization as a whole is a fiction of the media. …

Q: And what about Central Asia, where countries are seriously hoping for China to come in and develop infrastructure?

A: My personal opinion is that even in the South China Sea there is a greater chance to do something more together than in Central Asia. There are very few people in Central Asia, so it is not profitable to build there at all. Without a certain population density, all this is meaningless. …

Q: Donald Trump came to power promising to confront China along economic and political lines. Do you think he will do it?

A: Trump said he would improve relations with Putin, but he did nothing like that, and he even demanded that Russia withdraw from Crimea. At the same time, he promised to confront China, but has not done that yet. Many of us are happy about this, but I try to cool them: For him this is not a conscious choice; tomorrow his position can change. He is unreliable.

Q: Do you think this situation is beneficial for China?

A: I believe that in general, his policy will be confrontational. His advisers are very aggressive. … We do not know at all why he makes decisions, perhaps on the basis of his own views, or the views of his advisors, or the views of his daughter. It is impossible to work with that, and it is useless to try analyzing this. …

Q: In your works, you assert that the state has four characteristics that form its cumulative national power. Of these the most important are political power, economic power, cultural power and military power. While the last three components are clear, I wonder how to assess the political power of the state? Can it be quantified?

A: Of course. Three factors. The first factor is the will to reform. Second, the opportunity to implement reforms. Third, the direction of reforms. Will, opportunity and direction. The presence of will can be assessed by analyzing government policy and reading documents. Then we can look at what part of what has been planned is implemented, and understand the capabilities of the government. Finally, third, we look at the direction of reforms. Do they lead to the opening of the country to the world or to its closure? It is easy to calculate.

The opinions expressed in this blog post are solely those of the author.