Does Ukraine War Pose Greater Risk of Nuclear Armageddon Than Cuban Missile Crisis?

Updated Oct. 17 with comments from Olga Oliker and others.

This month humanity will mark the 60th anniversary of what American historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. described as the most dangerous moment in human history. But has his 1999 proposition remained valid? Or has the current crisis in relations between the U.S. and its allies on one side and Russia on the other become more dangerous than the Cuban Missile Crisis?1 If yes, then why? If not, then why not? These are the questions we have posed to some of America’s top experts on U.S.-Russian relations. We have also searched for answers to these questions in parallels drawn2 by not only experts, but also officials in the U.S. and Russia, between the current crisis and the Cuban Missile Crisis (CMC). Given the fog of crisis, it should, perhaps, come as no surprise that our search has revealed a significant divergence in answers to the questions we have raised. For instance, while Harvard’s Graham Allison and IMEMO’s Alexei Arbatov don’t believe the current crisis has reached the level of risk seen during the CMC yet, Stephen Cimbala of Penn State Brandywine and Lawrence Korb of the Center for American Progress see the “likelihood of a deliberate or miscalculated escalation to nuclear first use” as greater today than it was 60 years ago.

|

Those who say or imply that the CMC was more dangerous than the current crisis: |

Rationale for their assessment: |

|

Graham Allison, Harvard University: “October marks the 60th anniversary of the most dangerous crisis in recorded history.” (Arms Control Today, October 2022) |

“I agree strongly with President Biden when he said last week: ‘For first time since the Cuban Missile Crisis, we have a direct threat of the use of the nuclear weapon if things continue down the path they’ve been going.’ While this has not yet reached the level of risk in the Cuban Missile Crisis (where JFK judged the likelihood of nuclear war as ‘between one and three and even’) it has become the most dangerous confrontation in which nuclear weapons could potentially be used that we’ve had between the U.S. and the Soviet Union/Russia since.” (Graham Allison’s 10.12.22 response to RM) “The technologies of the day through which these communications were transmitted took 11 hours. In a case where messages were being sent about urgent issues, such delay obviously risked catastrophe.” (Arms Control Today, October 2022) |

|

Anatoly Antonov, Russian ambassador to U.S.: Russia and the U.S. "have not yet reached the peak of tension that existed 60 years ago.” (Kommersant, 10.13.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

|

Arbatov’s explanation of the differences between the CMC and today’s crises speak to some of the reasons why today’s situation may not be as dangerous:

|

|

Tulsi Gabbard, former member of the U.S. House of Representatives, and Daniel L. Davis, Defense Priorities: “The world is already at a greater risk of nuclear war than at any time since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.” (FP, 06.27.22)

|

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Matthew Bunn, Harvard University: “This is the worst danger of nuclear weapons being used since the Cuban Missile Crisis.” (Boston Globe, 10.13.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Angus King, U.S. Senator: “I believe this is the most dangerous moment, right now, this week, since the Cuban Missile Crisis.” (Maine Public, 03.16.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Fyodor Lukyanov, Russia in Global Affairs: “That period was indeed the most dangerous and it included not only the Caribbean crisis, but also others.” (Russia in Global Affairs, 07.28.22)3 |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Igor Kopytin, Russian war historian: “Now there is a game of nerves. This can be compared to the Caribbean crisis of 1962, when mental red lines that could not be crossed were set.” (Postimees, 03.14.22)

|

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Ernest Moniz, co-chair and CEO of NTI: “Regrettably, the 10th [NPT] Review Conference ... concluded without agreement on a final document after the Russian Federation blocked a consensus outcome. … It is another indication of the dangerous moment we face—where the risk of use of nuclear weapons is as high as at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis.” (NTI, 08.27.22) |

“Heightened tensions among nuclear weapon states pose an increased risk of miscalculation and escalation to nuclear war, with catastrophic humanitarian consequences.” (NTI, 08.27.22) |

|

Reid Pauly, Brown University: “We are not yet at the level of risk that we saw during the Cuban missile crisis, when events began to slip out of control. But the trajectory is not good.” (Yahoo News, 10.11.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Steven Pifer, Brookings/CISAC: “Washington and Moscow find themselves at the most contentious point in their relations since the early 1980s and perhaps since the 1962 Cuban missile crisis.” (CISAC, 05.23.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Sergey Radchenko, Professor, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (The Atlantic, 03.23.22) |

Radchenko pinpointed the decision by the U.S. and NATO to explicitly rule out engaging in a direct conflict with Russia over Ukraine as the main reason the current war is less perilous than both the Cuban missile crisis and the lower-profile 1983 Able Archer incident. (The Atlantic, 03.23.22) |

|

Jack Reed, U.S. Senate Armed Services Chair: “We’re in a situation that we have not seen since the Cuban [missile] crisis.” (Politico, 10.11.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Marco Rubio, U.S. Senator: called Russia’s invasion of Ukraine “the most dangerous moment in 60 years.” (Twitter, 02.27.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Ivan Safranchuk of MGIMO: “Russia and the United States have already descended to the lowest level of relations. But even the Ukrainian crisis did not become a ‘Caribbean’ one. You can, of course, expect that the ‘real Caribbean’ is yet to come.” (Russia in Global Affairs, 2022) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Mary Elise Sarotte, Professor, Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (paraphrased by interviewer): Certain dynamics that made the Cuban missile crisis so treacherous are, at this point, absent in the conflict over Ukraine. (The Atlantic, 03.23.22) |

Whereas the 1962 incident was sparked by the U.S. discovery of Soviet efforts to deploy nuclear-capable ballistic missiles to Cuba, today Russia has not taken a comparable step to directly threaten vital American interests, such as relocating “nuclear missiles closer to the U.S. or West,” Mary Elise Sarotte … told me [interviewer Uri Friedman]. (The Atlantic, 03.23.22) |

|

Katrina vanden Heuvel, the Nation: “[T]he 13-day standoff between the United States and the Soviet Union [is] widely regarded as the closest we ever came to global nuclear war.” (WP, 10.11.22) |

Didn’t offer explicit explanation. |

|

Those who say or imply that the current crisis is more dangerous than the CMC: |

Rationale for their assessment: |

|

Carl Bildt, former prime minister of Sweden: “We are in a situation potentially more dangerous than the Cuban missile crisis.” (WP, 10.10.22) |

“We are faced with a leader in the Kremlin who might actually mean what he says about this being a struggle for ‘life or death.’ We must do our utmost to deter Moscow—and all those there in positions to influence events— rom the ultimate insanity.” (WP, 10.10.22) |

|

Stephen Cimbala, Penn State Brandywine, and Lawrence Korb, Center for American Progress : “The likelihood of a deliberate or miscalculated escalation to nuclear first use is now as great, or greater, than it was during the fateful Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.” (Just Security, 04.12.22) |

|

|

Rose Gottemoeller, Stanford University: |

|

|

Sergei Karaganov, Russia’s Higher School of Economics : |

“When we had the Cuban Missile Crisis, we still dealt with responsible politicians who had gone through the Second World War. Now the level of political elites in the West is incomparably lower.” (Rossiiskaya Gazeta, 04.18.22) “We are living through a prolonged Cuban missile crisis. And I do not see people of the caliber of Kennedy and his entourage on the other side.” (NYT, 07.19.22) |

|

Nina Khrushcheva, New School: “We’re past Khrushchev,” she said, and pointed out that the Cuban missile crisis lasted only 13 days. The war in Ukraine is now in its 8th month. (Yahoo News, 10.11.22) |

“Putin seems to be more interested in not blinking than in getting out of the crisis.” Khrushchev “understood the human terms” of a potential conflict with the United States and never wanted the Cold War to lapse into mutual assured destruction. (Yahoo News, 10.11.22) |

|

John Mearsheimer, University of Chicago: “I think it’s actually more dangerous than the Cuban Missile Crisis, which is not to minimize the danger of that crisis.” (American Committee for U.S.-Russia Accord, 04.18.22) |

“I think … what we have here is a war between the United States and Russia and there’s no end in sight. I cannot think of how this can end in the near future. ... And I think there’s a serious danger of nuclear escalation here.” (American Committee for U.S.-Russia Accord, 04.18.22)

|

|

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy secretary of the Russian Security Council: The Cuban Missile Crisis had a "sobering effect on everyone—the leadership of the United States of America, NATO, the Soviet Union, the Warsaw Pact." “At that time there really was a Cold War, now the situation in some ways, in my opinion, is worse than then.” (Sputnik, 03.26.22) |

“At that time our opponents did not try to bring the situation in the Soviet Union to a boiling point with such a degree of fury” as they do now. (Sputnik, 03.26.22) |

|

George Will, Washington Post: “The nuclear threat may be graver now than in the Cuban Missile Crisis.” (WP, 10.12.22) |

“Vladimir Putin’s nuclear arsenal is immensely more varied and formidable than Khrushchev’s. And Putin’s frenzy intensifies as his Ukraine blunder reveals the hollowness of the great-power strutting it was intended to validate.” (WP, 10.12.22) |

|

Andy Weber, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense: “This crisis is more dangerous than the Cuban missile crisis.” (Politico, 10.07.22) |

There wasn’t a “hot war” in 1962 like there is now and Russia’s military doctrine allows for the use of nuclear weapons when faced with an existential threat, “which is how he [Putin] has defined Ukraine.” (Politico, 10.07.22) |

|

Vladislav Zubok, London School of Economics: Zubok told me [interviewer Uri Friedman] he views Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as more dangerous than episodes such as Able Archer and the Cuban missile crisis. (The Atlantic, 03.23.22) |

Not only is Putin less politically constrained than his Soviet predecessors, who had the Politburo to reckon with, but he is also presiding over a country that is far weaker than the Soviet Union was in its heyday, producing a uniquely destabilizing dynamic. (The Atlantic, 03.23.22) |

|

Those who say or imply the two crises are comparable, but do not explicitly say which is more dangerous: |

|

Joe Biden, U.S. President: “[F]irst time since the Cuban Missile Crisis, we have a direct threat of the use of the nuclear weapon if, in fact, things continue down the path they’ve been going. … We have not faced the prospect of Armageddon since Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis. ... It’s part of Russian doctrine that they will not—they will not—if the motherland is threatened, they’ll use whatever force they need, including nuclear weapons. I don’t think there’s any such thing as an ability to easily lose a tactical nuclear weapon and not end up with Armageddon.” (White House, 10.07.22) |

|

Sergei Lavrov, Russian Foreign Minister: When asked to comment on Harvard Professor Graham Allison’s assessment that the current situation is as dangerous as the Cuban Missile Crisis, Lavrov said that risks of a nuclear war are “quite substantial.” “The danger is serious, real. It must not be underestimated … Can this be compared to the Caribbean crisis? In those years, there was a channel of communication that both leaders trusted. Now there is no such channel. Nobody is trying to create it.” (RM, 04.26.22) |

|

Olga Oliker, Program Director for Europe and Central Asia, International Crisis Group: "Whether or not the present moment turns out to be more dangerous than the Cuban Missile Crisis depends on how it turns out. This seems glib, but I think that, while the desire to compare is understandable, comparison is not going to achieve what most of those asking for the comparisons seek, which is reliable prediction. Much as we might want it to, the historical experience of 60 years ago will not make it possible to predict what will happen in the days, weeks and months to come. Studying the past is still useful for drawing lessons. Nuclear war in 1962 was averted because of key decisions, both strategic and individual (e.g., respectively, President Kennedy decided not to invade Cuba and Vasily Arkhipov did not authorize the use of nuclear torpedoes from the diesel submarine he was on). We can trace similarities and differences in terms of time scale, real and perceived threats, brinksmanship and domestic politics. All that is useful. But it's useful in helping to formulate better policy, not predicting the future." (RM, 10.17.22) |

|

Sam Nunn, former U.S. senator: “We’re in the most dangerous period we’ve been in since the breakup of the Soviet Union,” Nunn said, comparing it to the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. ... “We have the threat of escalation, we have the threat of Russia bombing supply lines which would involve Poland and NATO. We have the increased dangers of cyber interference to command and control, [and] warning systems leading to blunder. The Russian invasion makes that all more likely. As you mention, we have the added danger of turning a nuclear power plant into a military base.” “It is a very dangerous time.” (South Bend Tribune, 09.25.22) |

|

Sergei Ryabkov, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister: “The approaching 60th anniversary of the Caribbean crisis, when the Soviet Union and the United States of America almost crossed the fatal line, has a direct projection on what is happening today in the context of a tough confrontation around Ukraine, where the collective West has actually unleashed a proxy war against our country.” (Kommersant, 10.13.22) |

|

Dmitri Trenin of Russia’s IMEMO: “The trajectory of the current crisis, in my opinion, is leading Russia and the United States to the last line, when the question of the physical survival of both countries and the whole world will arise. This is the main thing that unites the two crises. Sixty years ago, prudence prevailed at the last moment. Will it be the same now?” (Kommersant, 10.12.22) |

Footnotes

- We have chosen Feb. 24-Oct. 12 as the research period for our effort to capture the views expressed since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which led to the further dramatic deterioration of Western-Russian relations. The entries in each table are arranged in alphabetical order. This compilation is evolving and may be updated.

- It must be acknowledged that not everyone agrees that the two crises can be compared. For instance, Kori Schake of the American Enterprise Institute wrote in a 10.13.22 commentary for The Atlantic: “Biden’s comparisons of the current war to the Cuban Missile Crisis are wrong as history. The Cuban Missile Crisis was a standoff in which the Soviet Union moved to station nuclear weapons in an allied state abutting the U.S. As the political scientist Marc Trachtenberg has shown, it was the final act of earlier Berlin crises. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is not a direct U.S.-Soviet confrontation; the better analogies are proxy wars in third countries during the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s.”

- Russians have traditionally referred to the Cuban Missile Crisis as the “Caribbean crisis.”

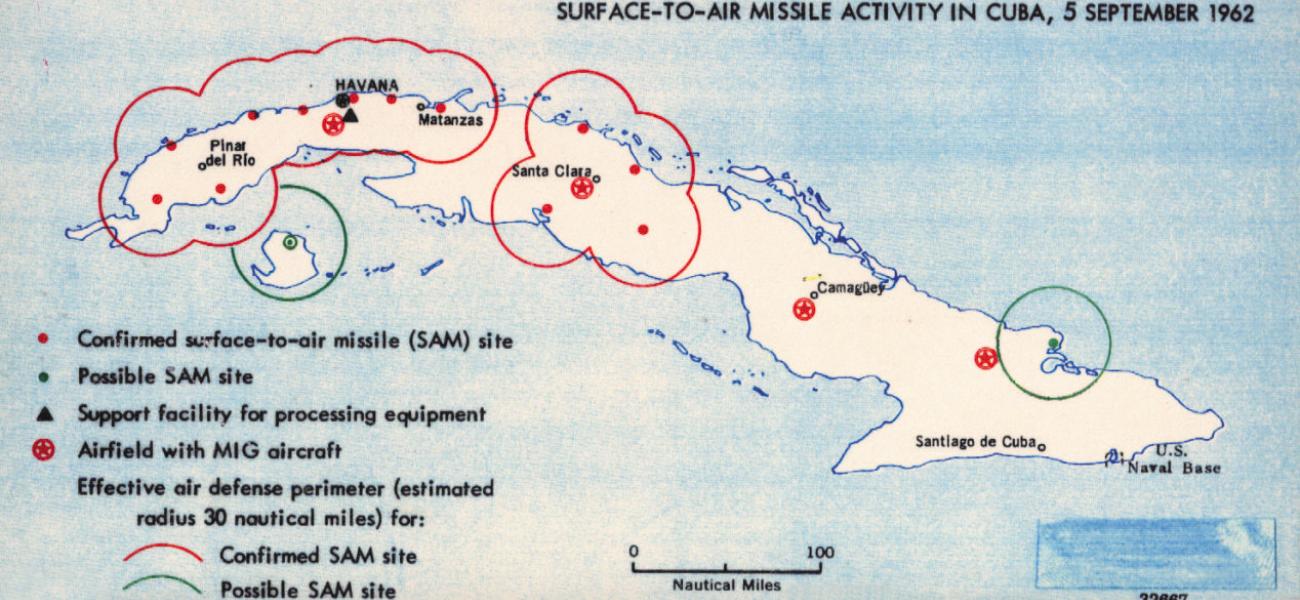

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the individuals quoted. Image by the CIA available in the public domain.