‘Accidental Czar’: A Creative Take on the Putin Biography

BOOK REVIEW

“Accidental Czar: The Life and Lies of Vladimir Putin”

By Andrew S. Weiss and Brian “Box” Brown

First Second, November 2022

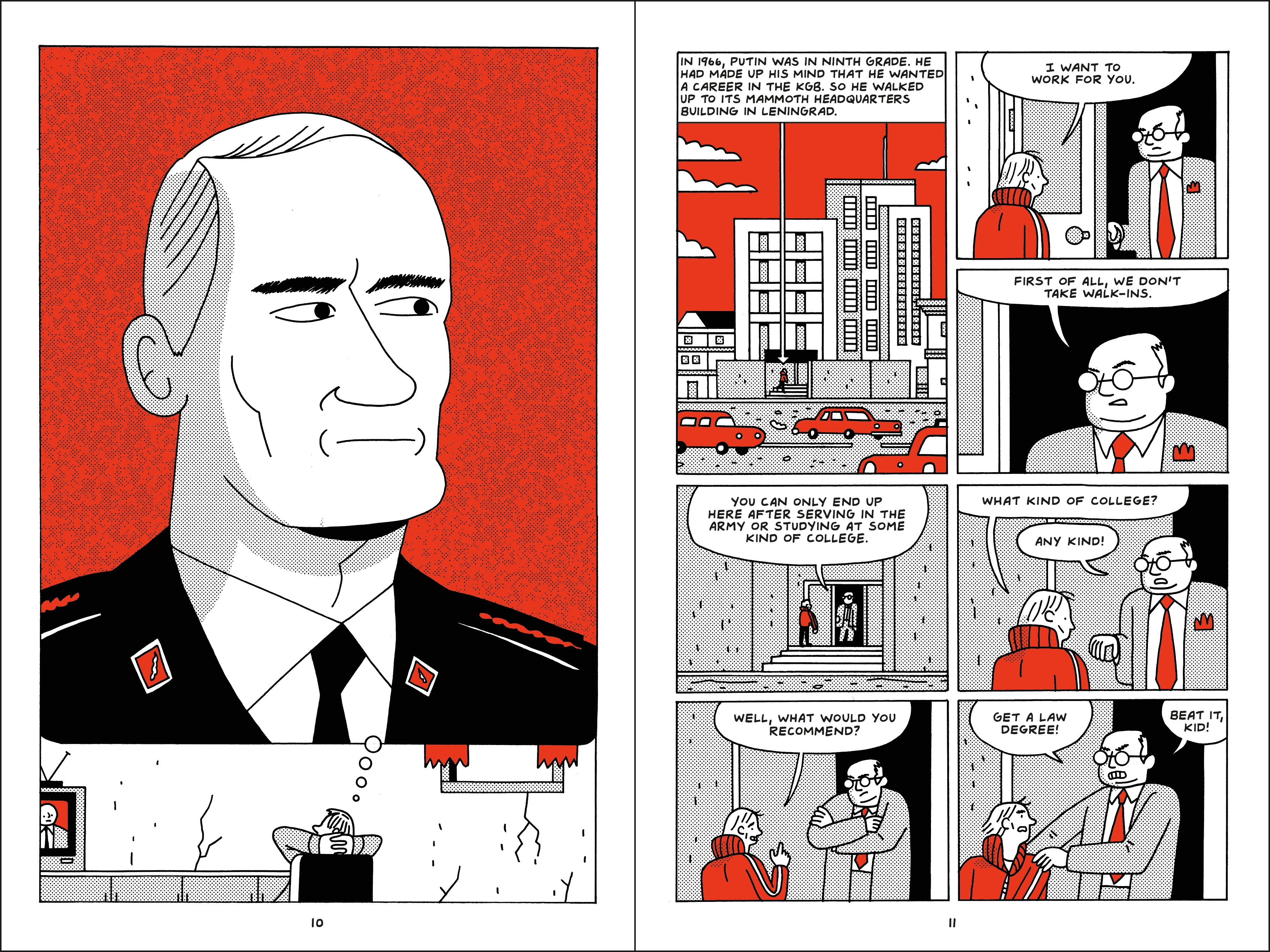

Andrew S. Weiss and cartoonist Brian “Box” Brown’s first-ever graphic biography “Accidental Czar: The Life and Lies of Vladimir Putin” opens with an arresting anecdote: thirty-something KGB officer Vladimir Putin in 1980s Leningrad, sporting a broken arm, boasts that “some punk on the subway was bugging me so I beat the crap out of him.”

Weiss and Brown use stories like this, in which Putin’s deluded self-image sharply contrasts with a less-than-heroic reality, as a window to the psyche, aspirations and pathologies of Russia’s longtime leader. Whether it’s adolescent Putin getting spooked by an aggressive rat he had cornered, or grown-up Putin confronting a (mostly imaginary) large crowd of East Germans as the Berlin wall was collapsing, these stories serve as an explanatory framework applied to much later actions undertaken by the Russian president at home and on the world stage. Unsurprisingly, this strategy is of little real use as a heuristic—though it makes for an often enlivening words-and-pictures portrait of a very troubled and troubling world leader. As a Slavist and comics scholar who has written on Russian and Eastern European comics, I will discuss the virtues and shortcomings of “Accidental Czar” primarily as a work of graphic narrative, i.e. what makes comics an advantageous or unsuitable vehicle for this type of material.

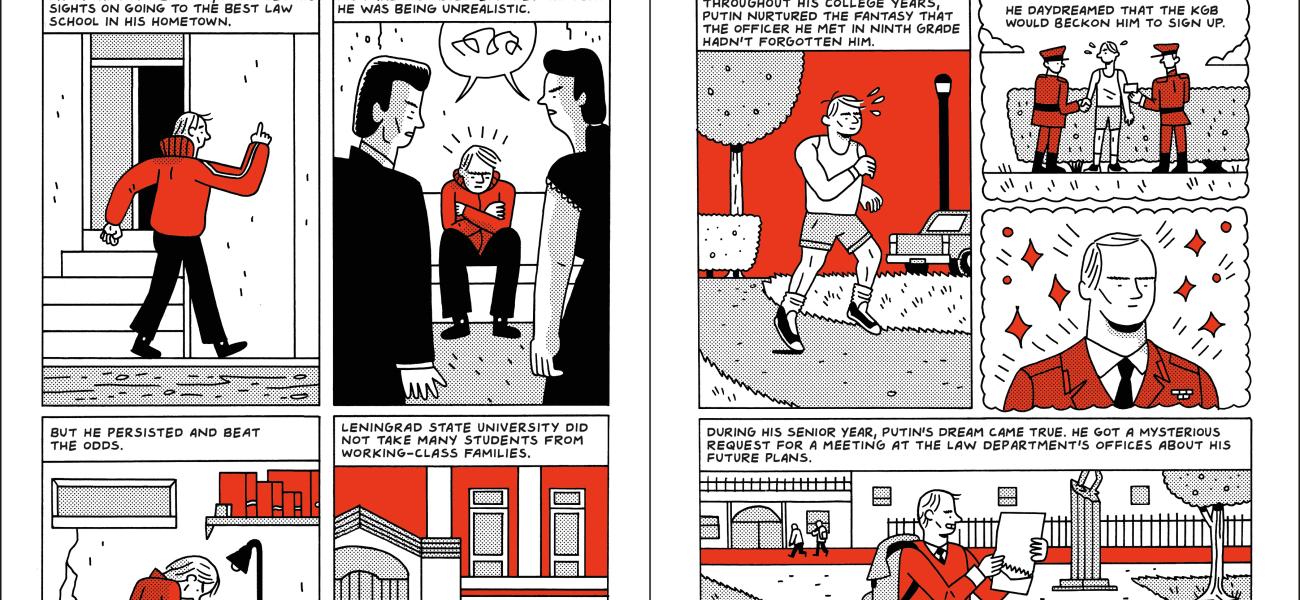

Weiss tells this tale as someone who witnessed part of it firsthand: he served in numerous policy roles at the National Security Council, the State Department and the Pentagon in administrations of both parties; today, he oversees research on Russia and Eurasia at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Brown previously released graphic biographies on wrestler André the Giant and performance artist/comedian Andy Kaufman. He has a clean, cartoony style, but takes few risks in terms of page design and storytelling. In any case, a cradle-to-present-day biography doesn’t really lend itself to risk-taking: there is much to cover, and the tendency is to fall back on no fewer than three panels per page (usually more like five or six) at an expeditious clip.

In Weiss/Brown’s near-psychoanalytic account, Putin acts out of deep insecurities brought on by an inferiority complex coupled with a Napoleon complex; a suspicious, even paranoid nature; and a fraught xenophobia—especially of the West—inherited from his ancestors. In a sense, Putin encapsulates, in a diminutive package, the worst of Russian culture as imagined by thinkers at home and abroad.

And yet, we have no choice but to deal with him. As Weiss writes in his foreword,

“We need to understand his motivations, along with the heavy burden of history that helped shape them. We need to see the parts of a man who is in many ways ordinary, even if the problems he has created are often extraordinary.” Hence chapters with titles like “Superspy,” “Into the Abyss,” “O Happy Man!” and “Feet of Clay,” as well as the chilling story of how Putin’s future mother was almost dumped in a mass grave during the WWII-era Leningrad siege and was rescued at the last moment by his injured future father, who had just returned from combat. Putin was born seven years later; on such slender threads do the fates of nations hang.

One of the more fun parts of the book deals with Putin’s fixation—shared with many of his generation—on the impossibly heroic Stierlitz (Vyacheslav Tikhonov) from the Soviet TV serial “Seventeen Moments of Spring” (1973). Putin modeling himself on the imaginary spy seems banal and pathetic, a feeling enhanced by Brown’s splash (a page made up of only one large image) of the young Putin daydreaming of himself in his idol’s role: the gigantic figure, some 95% of the page, overwhelms the tiny Volodya at the bottom: a cutting portrait of misidentification if I ever saw one. The large image works precisely because the book, as noted, mostly uses multi-panel pages made up of smaller pictures, which makes the occasional deviation from the pattern stand out. In any case, Putin’s inflated sense of self is soon punctured by Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin, deputy head of the Leningrad KGB Office, who drily reports, “He was a nobody.”

“Accidental Czar” features many fine uses of the comics form in this vein to liven up otherwise familiar (even trite) material. We see several world leaders, including Putin, with their hands on a globe, and an accompanying text box that reads: “[W]hat Putin really wanted, and still wants, is no mystery: for Russia to be a part of the board of directors that sets the rules for the rest of the world.” We also see Putin atop a pyramid, otherwise made up of lackeys, oligarchs, church leaders and ordinary citizens, to illustrate that Russian society operates on the basis of personal ties, not institutions or the rule of law. More creative uses of comics include President Putin berating someone over the phone, juxtaposed with a panel of identical size and composition showing the much younger Putin with a broken arm, still punching. (Maybe Putin’s later interest in judo emerged from such violent experiences.) Brown draws another amusing visual match between a present-day clean-shaven Putin crony and a bearded medieval vassal, to show that the roots of today’s rot run deep. Text/image tension also sometimes yields humorous results, as when the narration informs us that Putin considers the internet a “CIA project,” but the picture we see is of an innocuous AOL home screen and a 90s modem sound effect.

There have already been a number of fine Putin biographies, most notably Clifford Gaddy’s and Fiona Hill’s “Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin” (2015), Masha Gessen’s “The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin” (2013) and more recently Philip Short’s “Putin” (2022). It is not the remit of “Accidental Czar” to add anything new in terms of content, but rather to make its subject accessible to a different, wider readership. In this sense it succeeds, though those interested in much better comics works about contemporary Russia are directed to Victoria Lomasko’s “Other Russias” (2017) and Igort’s “The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks” (2016).

The comics industry in Russia (dating only to about 2008) has developed by fits and starts; the recent double blows of the COVID-19 pandemic and Western sanctions in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have largely brought it to its knees. Very few politically critical works have emerged since Putin took office, though in 2011 PR freelancer Sergei Kalenik and a pair of artists parodied the Putin cult of personality in the webcomic, “A Man Like Any Other” (“Chelovek kak vse”). These graphic works make fuller and more creative use of the comics medium to bring their complex subjects to life, in many cases precisely by focusing much more on the travails of ordinary people, not presidents. Still, “Accidental Czar” manages to convey some of what non-fiction comics can accomplish when utilized to explore the critical issues, history and people of Russia and Eurasia.

José Alaniz

José Alaniz is a professor in the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures and the Department of Cinema and Media Studies (adjunct) at the University of Washington, Seattle. He has published three monographs, “Komiks: Comic Art in Russia”; “Death, Disability and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond”; and “Resurrection: Comics in Post-Soviet Russia.”

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. All images from "Accidental Czar: The Life and Lies of Vladimir Putin" by Andrew S. Weiss; illustrated by Brian "Box" Brown, published by First Second, an imprint of Macmillan.