In the Thick of It

A blog on the U.S.-Russia relationship

Will Post-Soviet Russia’s Economic Gains Be Wiped Out by Ukraine War in 2022?

Three months after the Kremlin launched its invasion of Ukraine, economist Anders Aslund wrote that, by starting the war, President Vladimir Putin had “in a single day … wiped out most of the economic gains Russia had made since 1991.” CNBC issued a similar verdict in March. While the word “most” would typically mean more than 50%, Aslund clarified to RM that his assessment wasn’t meant to be strictly quantitative—more a turn of phrase to describe the scale of Western sanctions’ impact on Russia.1 Nevertheless, we think it is important to determine how much of Russia’s past gains in economic output may be erased by Putin’s war in Ukraine by the end of this year. Would the forecasted losses amount to more than half, i.e., “most”?

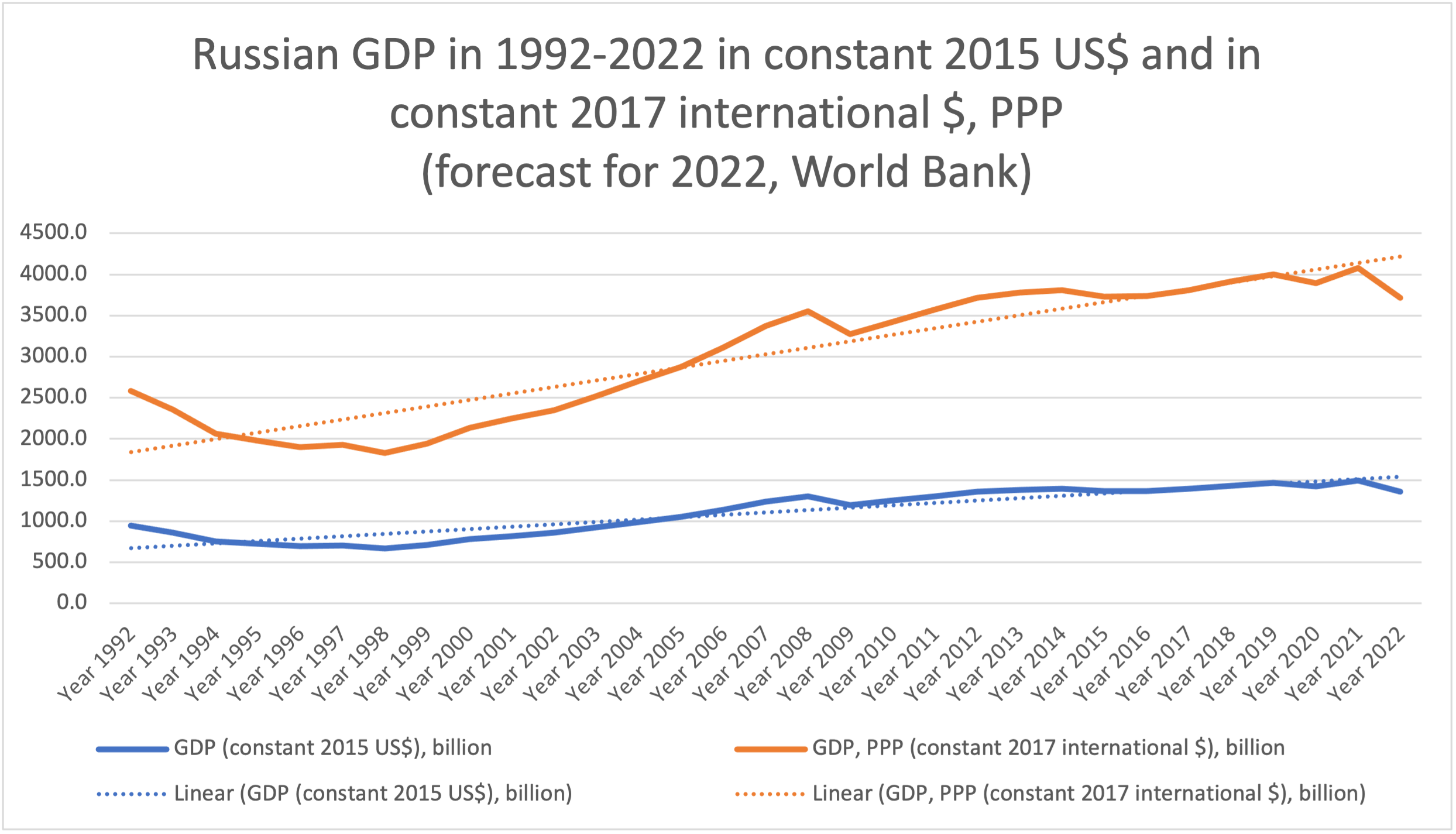

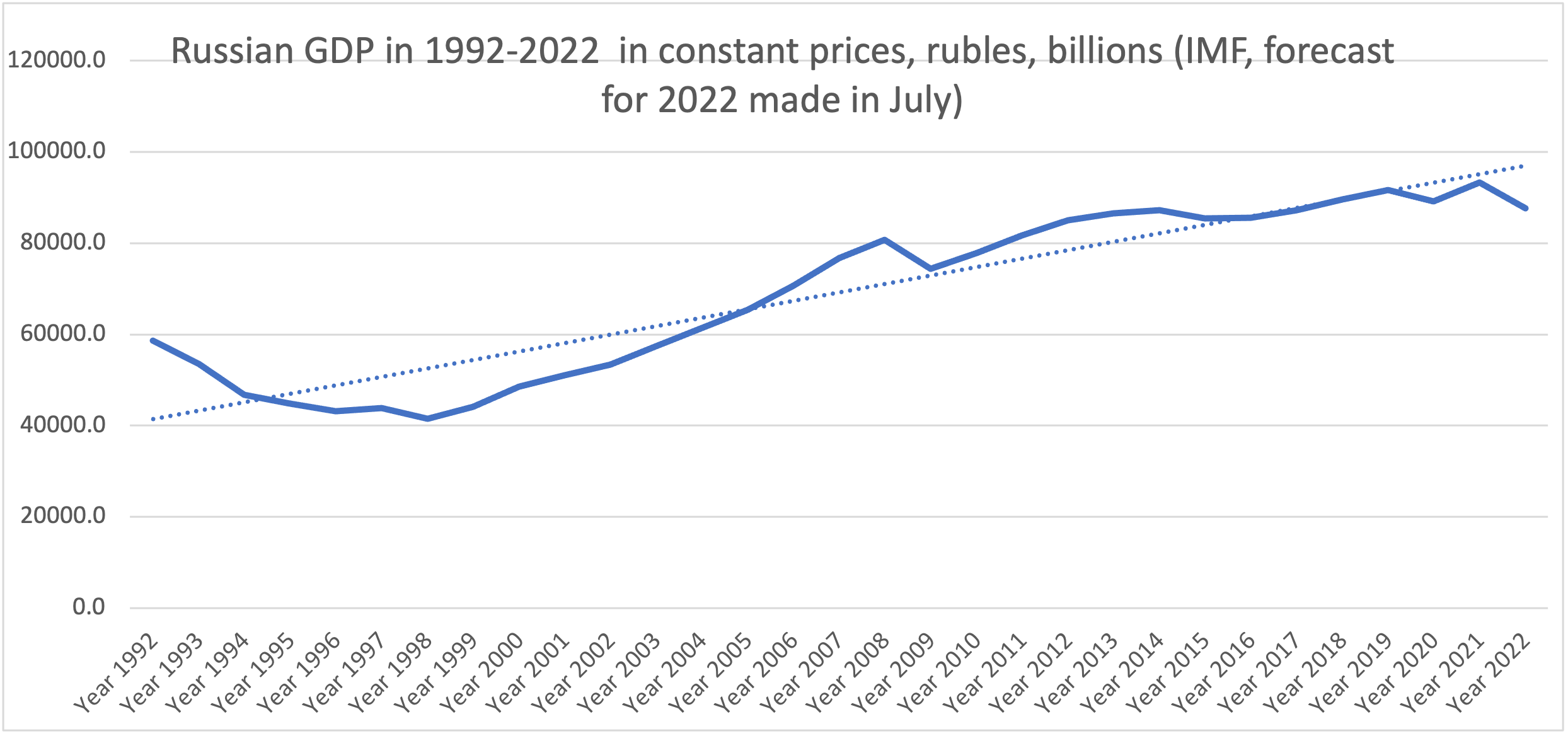

Here's what we found: If “economic gains” are measured as growth of GDP—the only metric for which sufficient data is available2—and if the latest projections of changes to Russia’s GDP in 2022 from the World Bank and IMF are more or less correct, then the decline in Russian economic gains this year will total about 16%-24% of the gains accrued from 1992 to 2021, which is far from “most.”

The table below shows the increase in Russia’s inflation-adjusted GDP from 1992 to 2021 by three different measures and the forecasted drop in GDP between 2021 and 2022, including the World Bank’s June 2022 forecast that Russia’s real GDP will contract by 8.9% this year and the IMF July 2022 forecast that Russia’s real GDP growth will total -6%.3

Here are the steps we took to test the claim:

- We downloaded World Bank and IMF data for measurements of Russia’s GDP in constant (i.e., inflation-adjusted) units, including (A) constant 2015 US$, (B) constant 2017 international $, PPP and (C) constant prices in rubles for 1992 (the first full year of the Russian Federation’s existence) and for 2021 (the last full year before the Kremlin launched what it calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine).

- We used that data to calculate the difference between Russia’s GDP in 2021 and 1992.

- We then obtained the World Bank’s and IMF’s forecasts for the change in Russia’s GDP in 2022 (assuming the World Bank’s applies to all types of measurements of GDP in constant units) and used these figures to calculate Russia’s projected GDP in 2022 and the difference between GDP in 2021 and projected GDP in 2022 in all cases.

- Finally, we divided the amount of the projected decline in Russia’s GDP in 2021-2022 by the amount of the increase in Russia’s GDP from 1992 to 2021 to see if the quotient equals more than 0.5 (i.e., 50%), to ascertain whether the predicted decline in Russia’s economic output in 2022 would, indeed, erase more than half of the gains in its economic output since 1991.

Footnotes

- In the article, Aslund did not specify what measure he used to calculate Russia’s “economic gains.” In response to our query, he clarified what factors he had in mind: “Russia ended the convertibility of the ruble. State ownership and other forms of privileged ownership are to expand greatly. Foreign direct investment has become impossible. Much of the trade with the West has ended… Putin is swiftly turning Russia into North Korea. Etc.”

- Alternative methods to test the claim could involve calculating changes in gross national income (GNI). However, the World Bank’s data for GNI in constant units—GNI, PPP, in constant international $ and GNI in constant US$—is reported only from 2012, while the IMF’s database does not contain GNI measurements at all.

- As stated above, the IMF’s July 2022 update predicted that Russia’s “real GDP growth” will total -6% in 2022. We asked the IMF how they measured growth for this update. A Sept. 8, 2022, response by the IMF specified that “real GDP growth” in the update is “the change of constant prices GDP in local (national) currency.” It should be noted that this update only contained percent change in GDP (and projections thereof) for 2020-2023. This is why we also used the IMF’s April 2022 World Economic Outlook, which contains full data on Russia for multiple decades, for measurements of Russia’s GDP in constant prices, rubles, for 1992-2021.

- The World Bank has tweaked Russian GDP figures for 2021 over the course of the year but the changes aren’t significant, so we’ve used data available as of early July 2022.

Photo shared under a Pixabay license.