The Shanghai Cooperation Organization: Development Hampered by Internal Conflicts

As we near yet another Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit, it is worth taking a look at this organization to try to understand whether it is a paper tiger or a powerhouse, and, if the latter, to attempt to discern whether this organization’s further evolution may have a tangible impact on the balance of power in Asia and Western allies’ interests in that region. Overall, while the capabilities of individual SCO members, such as China and Russia, pose a challenge to Western countries’ interests, due to internal challenges and a loose organizational structure, the organization itself does not.

Compared to whom?

To analyze the SCO’s strengths and weaknesses, I compare the organization with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). These organizations both attempt to create a form of Asian regionalism, have similar underlying principles and goals (regional security and development) and value a non-interference style of cooperation.

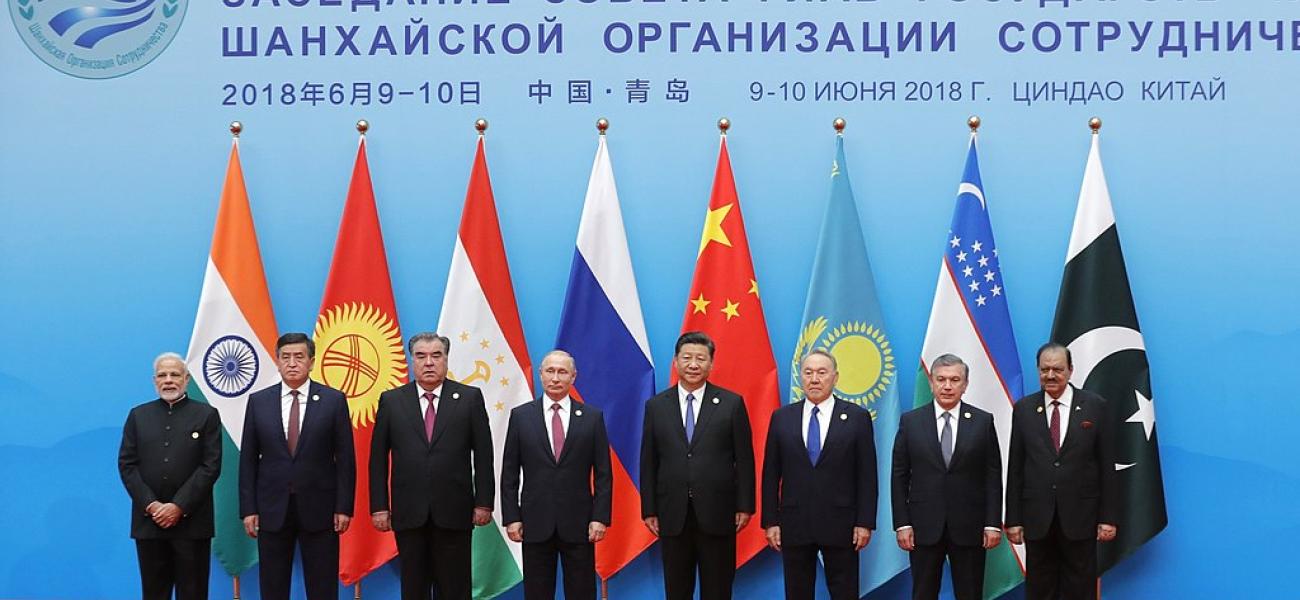

The SCO’s roots lie in the Shanghai Five, a political association between China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan established in 1996. The organization has grown steadily from its initial limited framework for negotiations on border demarcation, evolving into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in 2001 and adding Uzbekistan, Pakistan and India. As of 2020, the SCO is comprised of the eight aforementioned permanent members, four countries with observer status (Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia) and six discussion partners (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Cambodia, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Turkey). For its part, ASEAN was founded in 1967 by the five foreign ministers of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, with the goal of creating a common front against communism and promoting political, economic and social stability. These five countries were later joined by Brunei (1984), Vietnam (1995), Laos and Myanmar (1997) and Cambodia (1999).

The SCO’s stated goals are as follows: “strengthening mutual trust and neighborliness among the member states; promoting their effective cooperation in politics, trade, the economy, research, technology and culture, as well as in education, energy, transport, tourism, environmental protection and other areas; making joint efforts to maintain and ensure peace, security and stability in the region; and moving towards the establishment of a democratic, fair and rational new international political and economic order.” In comparison, ASEAN states that its key goals are “to accelerate economic growth, social progress and cultural development in the region,” to “promote regional peace and stability” and to “maintain close and beneficial cooperation with existing international and regional organizations,” among others.

SCO Total GDP, Military Strength Outstrip ASEAN; ASEAN’s Prospects For Economic Cooperation Remain High

Since 2001, the SCO has not only added new influential members but has also expanded its functions and added muscle by staging an increasing number of joint military and security exercises. A comparison of the SCO and ASEAN reveals that the military potential of SCO members is significantly higher than that of ASEAN members: SCO members’ combined armed forces total 8,293,000 people and their annual defense expenditures amounted to around 411 billion USD in 2019. In addition, four members (China, Russia, India and Pakistan) possess nuclear weapons with a capacity of 1987.3 gW and 7005 nuclear warheads. In contrast, ASEAN’s combined armed forces total only 2,432,000 persons and have no nuclear power. ASEAN members’ defense expenditures, meanwhile, added up to only 30.678 billion USD in 2019. Furthermore, ASEAN’s combined population is around 5 times smaller than the SCO’s, and while SCO members states’ combined GDP in 2019 totaled more than 19 trillion USD, ASEAN members had a combined GDP of only around 3 trillion USD.

ASEAN membership does, however, offer greater opportunities for trade. There is no free-trade pact so far for SCO member states, whereas ASEAN has “Free Trade Area” and “Comprehensive Investment” agreements and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC), which was launched in 2015. The SCO has been moving toward expanding trade opportunities as well, however. Since India and Pakistan were granted full membership in the SCO, South Asia has been included in the “SCO Economic Circle,” offering more room for multilateral economic cooperation between member states. Furthermore, in order to finance and provide banking services for investment projects supported by SCO members in the region, the SCO Inter-Bank Consortium was created in 2005. SCO members signed a memorandum of understanding on basic goals and directions of regional economic cooperation and have a program of multilateral trade and economic cooperation between members with short and long term objectives.

ASEAN Foreign Policy More United Than SCO

The SCO has ramped up its military cooperation in recent years, but member states tend to stop short of calling the organization an “alliance.” Over the past few years, the SCO’s joint military activities have expanded, include increased military cooperation, intelligence sharing and counterterrorism. SCO members held numerous multilateral military exercises and peace missions. The SCO has a well established legal system and long-acting mechanism for security cooperation (e.g. the agreement on regional anti-terrorism (RATS) that represents a solid legal basis in order to fight the “three evils”: extremism, terrorism and separatism).

However, these enhancements do not mean that the SCO is an “alliance.” The SCO Charter calls for “mutual respect of sovereignty, independence, territorial integrity of States and inviolability of State borders, non-aggression, non-interference in internal affairs, non-use of force or threat of its use in international relations, seeking no unilateral military superiority in adjacent areas.” The SCO describes itself as a “permanent intergovernmental international organization” and includes member-states, observer-states, and dialogue partners. These statements do not necessitate that the SCO be an “alliance.” Also, although Russian journalists and Pakistani columnists have referred to SCO members as allies, Kazakh diplomats insist that the SCO is not an alliance and Putin has avoided using this term as well.

ASEAN’s structure is a bit different, as member states value more bilateral cooperation in this field. In the words of a former Malaysian official:

Bilateral defense cooperation is flexible and provides wide-ranging options. It allows any ASEAN partner to decide the type, time and scale of aid it requires and can provide. The question of national independence and sovereignty is unaffected by the decision of others as in the case of an alliance where members can evoke the terms of the treaty and interfere in the affairs of another partner.

In ASEAN, there is an emphasis on informal structures and personal relationships that are cultivated away from official meetings. ASEAN seeks security by widening its process of dialogue, consultation, consensus and confidence‐building to cover the Asia‐Pacific region in the form of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF).

Both organizations have an annual summit of political leaders, but, as previously noted, the SCO doesn’t refer to itself as an alliance. The SCO is more of a partnership; a regional security apparatus that continually expands the areas of cooperation among its members. ASEAN, meanwhile, has a high level of foreign policy convergence, as seen in its participation in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), and ASEAN members have a decision-making process based on consensus. According to experts, ASEAN went from a policy of “non-interference” to “frank discussions”. They now seek an informal and incremental approach to cooperation through the Retreat1 framework.

Despite Development, Significant Obstacles to Cooperation Remain

In spite of recent expansion, the SCO faces a number of serious obstacles, especially in the form of territorial disputes, signifying that while individual members of the organization are quite strong, the organization itself possesses some fundamental contradictions. Disputes have taken place between three of its members, all of which are nuclear powers: China, Pakistan and India. In order to ease tensions, the members will have to address the ongoing disputes between China and India over the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh. Furthermore, the rivalry between Pakistan and India will also have to be tempered, as the South Asian neighbors’ conflict about Jammu and Kashmir is more than ever a source of turmoil.

Thus, the next SCO summit’s agenda (postponed to the fall due to the pandemic) will be partly focused on ensuring regional stability and peace. To achieve these goals, they will have to not only work on fighting COVID-19 but also on ensuring economic growth. On the one hand, during the last meeting with SCO members, China said it was ready to start mechanisms in border regions to ensure safety regarding the pandemic. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs assured the body of China’s will to multilateral cooperation with SCO members and other actors as well. On the other hand, according to Vikas Swarup, Secretary at India’s Ministry of External Affairs, contributions to the trade and economic agenda will be a main focus of this summit as well, as members will try to build long-term economic and energy linkages.

The SCO also aims to reaffirm its presence and utility in Eurasia and step up as a multilateral organization at the 2020 summit. The SCO needs to demonstrate its utility among its members and to other multilateral organizations, even though it remains difficult to have a universal list of criteria to judge the success of an international regional organization. It still needs improvements to become a strong, consolidated, expanded and efficient multipurpose organization that fully controls regional security, promotes economic cooperation, increases people’s prosperity (through its investment bank, for instance), provides a platform for communication and plays an important part in the world.

Conclusion

The SCO has been gaining strength steadily since its inception in 1996, developing not only security but also military cooperation with its 2003 ground exercise, Coalition-2003, the first combined military exercise in which the Russian and Chinese armies participated. Nonetheless, however, the SCO is plagued by internal contradictions that hamper its ability to fully utilize its power as an organization. Russia’s success in bringing India in as a full member in 2017 invited accusations from some watchers of Sino-Russian relations, saying that Russia seeks to dilute China’s leadership in that organization by integrating New Delhi. Moscow has also delayed on the establishment of an investment bank that would have provided more clout to China in the region. Finally, the adversarial relationship between India and Pakistan limits opportunity for reaching a consensus on military and security cooperation within the SCO, as do the disputes between three nuclear member states (China, India and Pakistan) over territory. Given all of these internal challenges, while the capabilities of individual SCO members such as China and Russia do pose a challenge to Western countries’ interests, the organization itself does not.

Footnotes

- The Retreat is the first gathering of the ASEAN Foreign Ministers in 2020 under the theme “Cohesive and Responsive ASEAN.”

Lucie Messy

Lucie Messy is a recent graduate of Lille Catholic University, where she studied international relations.

Photo by Kremlin.ru, shared under a CC BY 4.0 license.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author.