Russia’s Impact on US National Interests: Preventing Nuclear War and Proliferation

Editors' note: With a change of guard in the White House, the new U.S. administration has a chance to commission a review of U.S. domestic and foreign policies. This primer is the fourth in a series designed to facilitate such a review by detailing the impact Russia does or can have on each of five vital U.S. national interests as defined by a task force co-chaired by Graham Allison and Robert D. Blackwill. Some of the authors offer recommendations on how to best advance these interests in 2021-2024. The interests are: (1) maintaining a balance of power in Europe and Asia; (2) ensuring energy security; (3) preventing the use and slowing the spread of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction, securing nuclear weapons and materials and preventing proliferation of intermediate and long-range delivery systems for nuclear weapons, addressed below; (4) preventing large-scale or sustained terrorist attacks on the American homeland; and (5) assuring the stability of the international economy.

Executive Summary

Understanding the potentially apocalyptic consequences of nuclear war, it is clearly in the national security interest of the United States to reduce nuclear risks. This necessitates a multilayered effort to slow the spread of nuclear weapons and technologies, reduce nuclear stockpiles, secure nuclear materials and prevent the proliferation of delivery systems for nuclear weapons. None of these efforts can be truly successful without the help and cooperation of the Russian Federation. Indeed, the Russian impact on U.S. nuclear risk reduction goals cannot be overstated. Russia’s arsenal constitutes over 45 percent of the global nuclear stockpile. Those weapons are coupled with delivery systems that could reach American soil in about 30 minutes, meaning Russia presents a clear and ever-present existential nuclear threat to the United States. U.S.-Russian bilateral nuclear risk reduction efforts have produced successes in the past, but those efforts are now fading and failing. Should the United States want to continue to reduce nuclear threats in the 21st century, it has no choice but to engage in a reinvigoration of nuclear policy dialogue and cooperative activities with Russia.

Nuclear tensions between the United States and Russia, and around the world, are now at the highest levels seen since the end of the Cold War. These conditions mandate that the United States take a leadership role in stabilizing the situation. That will require some immediate actions, including extending the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) and managing the aftermath of the collapse of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF).

There are also longer-term steps the United States can take to facilitate cooperation and dialogue with Russia that will aid in its goal of reducing nuclear threats. Washington, working with Moscow, will need to rebuild teams capable of producing a new generation of arms control and nonproliferation agreements. It will also be necessary to restart dialogues and deal with longstanding grievances, including treaty compliance, confusion about each other's doctrines relating to nuclear use and missile defense. These interactions should be regularized and protected from broader challenges the United States faces from Russia. Beyond that, substantive discussions over nuclear issues need to be reinvigorated and broadened to include emerging threats like hypersonic weapons and the incorporation of artificial intelligence into strategic command systems. These discussions cannot be sporadic fora in which to enumerate past grievances; rather they should encourage bold and creative thinking about the future of both arms control and nonproliferation.

Beyond nuclear arms control and nonproliferation discussions, the United States should press Russia to expand cooperation to contend with conventional arms control challenges like the very likely collapse of the Open Skies Treaty, from which the U.S. and Russia have now both withdrawn, as well as the continuing threat of nuclear terrorism and the need for nuclear security cooperation. The United States should also see if Russia has any interest in working together to expand all these efforts into multilateral formats.

Incoming U.S. President Joe Biden has long supported nuclear risk reduction measures and it is likely that his team has already considered the initial pressing challenges and how to confront them. All of the new U.S. administration’s policy goals in this space will unavoidably be impacted by Russia. Through its nuclear assets, nuclear posture and political choices, Moscow affects how Washington plans and implements its own nuclear policies in arms control, nonproliferation and nuclear security. The same, of course, is true in the reverse. It is for those reasons that the two countries are “doomed to cooperate.”

With a renewed acknowledgement of the stakes, a stabilization of remaining structures and a commitment to substantive dialogue and adequate resources, the United States, working with Russia, can achieve its goal of reducing nuclear risks for themselves and the world.

Russia’s Nuclear Assets and Posture

In order to understand how Russia’s nuclear policies affect the United States, it is necessary to understand the scope and purpose of the Russian arsenal.

Despite significant reductions, the Russian nuclear arsenal and delivery systems still present an existential threat to the United States and its allies. Down from a peak of over 40,000 nuclear weapons in the 1980s, Russia currently has around 6,400. Of those, 4,000 are in the active nuclear stockpile, which includes 1,550 deployed strategic nuclear weapons. There is some dispute over the exact number, but Russia is believed to also possess between 1,000 and 6,000 non-strategic (i.e., shorter-range, lower-yield) nuclear weapons, emplaced on land, air and sea delivery systems. The Russians are now approaching the end of a nuclear modernization program that replaced or upgraded many Soviet-era systems. They are also pursuing a slate of “exotic” delivery systems designed to evade missile defenses.

Russia’s reliance on nuclear weapons in its defense strategy has been increasing since the end of the Cold War due to a perceived imbalance with NATO conventional capabilities. This is not dissimilar to the posture that the United States and NATO pursued in the early days of the Cold War, when they felt like their conventional forces could be overrun by the Soviets.

Among experts in the United States and NATO countries, the current debate over Russia’s nuclear posture is centered on the conditions under which the Russians might use nuclear weapons and whether they would use nuclear weapons first.

One of the facets of that concern is related to “escalate to deescalate” (E2D), specifically the concept that a country losing a conventional war could use a low-yield nuclear weapon to unreasonably raise the stakes, causing its opponent to seek terms to end the conflict and avoid an all-out nuclear war. In its 2018 Nuclear Posture Review, the Trump administration argued that Russia has an E2D policy, specifically focused on employing nuclear weapons on a limited basis in order to end a conventional conflict with NATO. Citing ample evidence, many experts argued that E2D is not the Russian approach, and that Russian strategists know that any use of a nuclear weapon could lead to an all-out nuclear war.

In June 2020, perhaps in an attempt to quiet some of the misperceptions, the Russian government published a paper outlining its own views on deterrence. While some experts believe the document did not indicate a change in military doctrine, it did provide some clarifications and insight into Russian views. Framing its arsenal as a deterrent to be used only in extreme circumstances, it did reaffirm the notion that Russia would use nuclear weapons in response to any action, including conventional attacks, that “threatens the very existence of the state.” The paper retains a fair bit of ambiguity, however, and some experts find that, while the bumper sticker of “escalate to deescalate” might be overly simplistic, the option of preventive or preemptive strikes is clearly available to both the United States and Russia. (See Appendix 1.)

What is also clear is that in order for the United States to pursue nuclear risk reduction efforts, it needs to get a better understanding of the Russian nuclear doctrine through direct and multi-level dialogues.

Russia’s Impact on Nuclear Strategic Stability and Arms Control Goals

The United States has come to the edge of a nuclear nightmare more than once, but most notably in the form of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Since then, Washington has engaged Moscow, its peer nuclear competitor, in almost 60 years of bilateral nuclear diplomacy to prevent such a nightmare from ever happening. From basic agreements over crisis communication to robust treaties involving rigorous inspection mechanisms, the United States increased its own security by engaging with the Soviet Union and later Russia. With ebbs and flows along the way, these efforts were largely shielded from the broader disputes between the two countries.

Unfortunately, the current state of what many experts call “U.S.-Russian strategic stability”1 is bleak. Together, the two countries possess over 90 percent of the global nuclear stockpile and the guardrails the United States built with Russia to prevent disaster are crumbling. Some treaties and agreements have expired naturally but were not replaced. Others, like the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) and the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) were abandoned.

With the last major bilateral arms control agreement, New START, teetering on the edge of collapse, the United States and Russia now find themselves at a crossroads between cooperation and catastrophe. In order to avoid further deterioration of the situation, leaders in Washington must engage leaders in Moscow to stabilize what is left of their bilateral arms control regime. They must then commit to creating a new generation of arms control agreements.

Russia’s Impact on Nuclear Nonproliferation Goals

Preventing the further spread of nuclear weapons is among the highest security priorities for the United States and Russia can impact that goal both positively and negatively. As one of the three “depositary governments” named in the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT), Russia has a significant amount of influence in the international bodies that deal with nonproliferation issues, including the U.N. Security Council and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). The United States has partnered with Russia on a number of nonproliferation efforts, including the P5+1 talks with Iran and Six-Party Talks with North Korea. Moscow’s ability to bring economic and political pressure to bear on countries of proliferation concern can outweigh Washington’s. However, Russia is also a potential source of sensitive equipment, materials and technology that could enable proliferation. That fact must be monitored and managed.

There is no doubt that the Trump administration’s abandonment of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), a.k.a. the Iran Deal, and feckless attempts to contain the North Korean program will negatively reflect on future U.S. efforts to engage in nonproliferation efforts. Russia may also seek to take advantage of the United States’ damaged reputation in fora like the upcoming NPT Review Conference.

Though political maneuvering should be anticipated, it should not be allowed to become a source of conflict when pursuing nonproliferation goals. Russia’s commercial nuclear interests in Iran make it an indispensable partner in any future talks over Iran’s nuclear program. Further, while Russia appears to prioritize stability in North Korea over requiring the country to forgo its nuclear arsenal, President Vladimir Putin’s 2019 meeting with Kim Jong-un could have created some influence with the North Korean leader. That could be of use in future talks with Pyongyang. Finally, when creating a multilateral sanctions regime targeting Iran, North Korea or any other possible proliferant, Russia would be an essential partner in enforcing those regimes.

The prevention of further proliferation to new countries is a U.S. goal, but stemming the spread of nuclear weapons is in everyone’s interest. The incoming administration should seek to engage Russia in a wide-ranging dialogue on proliferation prevention with that in mind.

Russia’s Impact on Nuclear Security Goals

Nuclear terrorism is a probability-low and consequence-high threat to the United States. Given the size of Russia’s nuclear weapons and material stockpile, the United States has had an interest in mutual work to secure and safeguard these assets. Current unclassified estimates suggest that in addition to its nearly 6,400 nuclear warheads, Russia has about 679 tons of highly enriched uranium (HEU) and around 190 tons of separated plutonium, located in buildings and bunkers throughout the country. Experts and observers do have concerns about the safety of these materials and Russia’s recent attention to and investments in nuclear security. Those concerns are not new.

Following the end of the Cold War, the United States was extremely worried about the sale or theft of nuclear weapons or materials from the various newly independent states that made up the former Soviet Union. Through efforts like the Cooperative Threat Reduction Program, the United States worked with Moscow to reduce those threats. Overall, security and accounting for Russia's weapon-grade fissile materials has dramatically improved over the past 25 years, but there are still major weaknesses stemming from the threat environment in which Russia operates, including major corruption and the potential for insider theft. How well Russia has managed COVID-related risks to nuclear security is still to be determined; it has been reported that workers at two of Russia's 11 nuclear power plants have contracted COVID.

Despite the long history of U.S.-Russian cooperation on securing nuclear materials and facilities, cooperation has faltered and now, in some cases, it is prohibited. Russia has terminated a 2013 bilateral agreement on nuclear energy research and development, as well as a 2010 agreement with the U.S. Department of Energy on converting six Russian research reactors to low-enriched uranium fuel. The two countries are also in a standoff about the future of the Plutonium Management and Disposition Agreement (PMDA), which committed each country to dispose of at least 34 tons of their weapons-grade plutonium stockpiles—enough for thousands of nuclear weapons. Putin suspended Russia’s participation in this agreement in 2016, citing U.S. inability to fulfill its requirements, as well as non-nuclear issues such as NATO expansion and economic sanctions relating to Russia’s activity in Ukraine. Five years later, the dispute remains, as do the plutonium stockpiles (although Russia has processed some plutonium into MOX fuel as stipulated by the PMDA).

Resolution of all current nuclear security disputes will take effort, but there are mechanisms that can facilitate progress. While Russia’s support for the Nuclear Security Summit (NSS) process initiated by former President Barack Obama waned for political reasons, the United States and Russia still co-chair the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism (GICNT). The GICNT has 89 participating states, including every nuclear-armed state except North Korea. The work of the group should be supported and expanded in the years to come. The further exchange of best practices, discussion of common challenges and technological cooperation will help the countries and the world better manage and control the threat of nuclear terrorism. Some U.S. experts have also recommended reforming bilateral nuclear security cooperation by sharing expertise, jointly developing approaches to cope with new threats and lifting a congressional restriction on funds for defense nuclear nonproliferation.

Immediate Actions

Understanding that U.S. nuclear policy goals and objectives are influenced and impacted by Russia, there are a few tasks that the incoming Biden administration should pursue as a matter of practicality and urgency.

First, the United States and Russia should decide on the future of New START. Fortunately, the actual extension of the treaty can be done through an exchange of diplomatic notes. On the U.S. side, per the 2010 Senate Resolution of Ratification, the Senate does not need to approve the extension, but it does need to be informed. If the administration wants a new or augmented deal, that would require the advice and consent of the Senate. On the Russian side, the extension does need to be formally approved by the State Duma, parliament’s lower house, but that can be accomplished quickly.

The Biden administration now has about two weeks in which the U.S. and Russian presidents can agree to extend New START. The new president has already publicly signaled his support for extension, citing the predictability and stability New START affords and the need for time to negotiate new agreements, which will require lengthy and difficult discussions over scope and verifications measures.

The United States and Russia do not have to extend New START for the maximum five years allowed under the treaty. Some experts contend that the United States should choose to extend the treaty for a smaller period of time (or several smaller periods of time, if that proves legal) with the hopes that it would spur efforts toward a new, expanded treaty negotiation that would include more Russian nuclear weapons and delivery systems. Such a strategy would likely create one or multiple crisis points each time the treaty was set to lapse again.

The United States and Russia could also choose to let the treaty expire and seek negotiation of a new New START-like agreement. This option would have little global support, including among U.S. allies, and it would leave the two countries without any on-the-ground or regularized insights into each other’s strategic arsenals. While the parties could seek a continuation of stabilizing activities, like a voluntary data exchange in the interim period, there would be no guarantee that either side would consent to such activities outside of a formal agreement.

In the end, the decision should be clear: From both a security and economic perspective, extension just makes sense. Entering the next 75 years of the nuclear age with no legally binding constraints on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals defies logic and reason. New START has worked and will continue to, if faithfully implemented by both sides as it has been since taking effect. It offers predictability and stability that allows for clear-eyed force structure planning. Neither side can buy the kind of intelligence that the treaty provides. Even if the two countries tried and did divert time, resources and energy into gathering this intelligence independently, instead of through consensual data-sharing and verification, the resulting information would not be as good. Besides, with the COVID-19 crisis far from over, it would be foolish to spend resources on things that could be effectively free. The extension would also give both parties more time to decide on what comes after New START, including when and how to include China, France and the United Kingdom in such discussions.

The second pressing practical matter relates to dealing with the aftermath of the INF Treaty’s collapse, which has dramatically raised the danger of an intermediate-range (IR) missile race. While neither side is likely to concede any fault over the situation, the consequences of the collapse can and should be managed. The United States should pause and review any Trump-era plans to develop ground, sea and air-launched IR missiles, press Russia to outline its own plans regarding IR missile production and deployment and reciprocate. This transparency effort would not just be useful on a bilateral basis, but also for countries that are concerned about IR missile proliferation around the globe. In order to be successful, Russia would need to acknowledge, rather than accept, the U.S. charge that the 9M729 missile is an intermediate-range system and incorporate the missile into the transparency effort.

Washington should then engage Russia to open a dialogue specifically focused on the prevention of an IR missile race. This dialogue could cover a range of issues, including prohibitions on nuclear-armed IR missiles and specific geographic restrictions on IR missile deployments. With this added stability, the two countries could discuss what future bilateral or multilateral controls on IR missiles could look like, while also engaging other IR missile-possessing states in the conversation.

Next Steps: Rebuild, Restart, Resolve, Reinvigorate

Having dealt with the most pressing nuclear challenges that Russia poses for the United States, Washington should then turn to next steps, while acknowledging there is a lot of old baggage that is getting in the way. The Obama administration’s attempt to “reset” the relationship with Russia was much maligned, but the desire to create a clean slate from which to operate was understandable. Resetting might just be a step too far, as it implies that slights and offenses, both real and imagined, can be forgotten. The Russians perceive that the United States withdrew from the ABM Treaty and other agreements, like the Iran deal and Open Skies, without just cause. The Americans perceive that Russia has been and is continuing to engage in multiple treaty violations. Saying a reset button has been hit does not change that reality. That is why the United States should think about future engagement with Russia as the continuation of a long and sometimes difficult process that has ably served the security of both countries. In order for the process to continue yielding benefits, perhaps the incoming Biden administration can consider some different “re”-prefixed verbs: rebuild a team, restart a dialogue, resolve to deal with key grievances and reinvigorate the dialogue by including new topics.

Rebuild a Team

To create a new generation of nuclear risk reduction structures and agreements, the United States will need to rebuild its capacity for dialogue and diplomacy. On the U.S. side, shifting priorities, natural retirement, neglect and bureaucratic obstacles have reduced the number of people working on U.S.-Russian strategic stability, nonproliferation and nuclear security. While the Russians are not as transparent about their staffing issues, one can assume they are experiencing similar challenges. New staff should be hired en masse and properly integrated with old guard experts in order to better support the transfer of historical knowledge. Not only will it be necessary to increase the number of people working on this matter, it will also be imperative that a range of technical, scientific, legal, political and language experts be brought into the fold. Diversity should also be promoted, both in terms of gender and background. With the myriad U.S.-Russian nuclear challenges on the horizon, leaving more than half of the population out of the conversation is unwise.

Restart a Dialogue

With bigger, more diverse teams in place, the United States should work with Russia to restart a general dialogue about a range of nuclear risk reduction issues. This is easier said than done. Skeptics in the United States will point to Moscow’s continued interference in U.S. politics, Russian treaty compliance and sporadic interest in further progress on nuclear risk reduction as evidence that engagement is not worth the effort. Russian critics, for their part, can point to two decades’ worth of destructive U.S. withdrawals from treaties and agreements, sometimes with specious justification, as proof that the United States cannot be trusted to keep its word. The inability of the United States and Russia to save the INF Treaty seems like a clear demonstration of a lack of motivation and will to engage in the difficult work of creating and maintaining mutual restraints.

Of course, tackling these challenges has been made more difficult by the COVID-19 pandemic. In-person meetings come with safety concerns and it does not appear that the United States and Russia have a mutually acceptable set of secure online communications tools for the purpose of substantive dialogue, much less negotiations.

Even faced with those constraints, it is in the U.S. national security interest to convene and sustain a new, robust and multilayered dialogue between the two nations. These conversations should not be confined to small groups of diplomats, nor should they consist of one- or two-day interactions. Various groups of experts from all relevant parts of the U.S. and Russian governments should engage in regular, open-ended conversations. Non-governmental dialogues should also be encouraged. While COVID-19 continues to impede in-person meetings, secure online communications should be established and used. When in-person meetings are again possible, they should take place in a neutral setting. Geneva and Vienna have been common sites for discussions and negotiations in the past, but they are also crowded with international bureaucracies, curious reporters and even the ghosts of past arguments and failures. Perhaps a little metaphorical breathing room would help facilitate a more productive dialogue. Given multiple European countries’ interest in supporting global arms control and non-proliferation matters, it would not be difficult to find a new venue or venues. Discussions on short-term next steps could range from future nuclear reductions and controls on delivery systems to non-strategic nuclear weapons and the blurring between strategic and conventional military planning, as well as a bilateral effort to globalize cooperative threat reduction activities. Furthermore, any self-imposed or legislatively mandated restrictions on military-to-military and lab-to-lab exchanges should be lifted and the interactions should become a standard occurrence or even a semi-permanent activity.

These dialogues can and would help rebuild the muscle memory needed to strengthen existing U.S.-Russian nuclear risk reduction structures and regimes, as well as the next generation of those structures and regimes.

Resolve to Deal with Key Grievances

The airing of complaints, misconceptions and accusations that happens at formal and informal nuclear weapons policy events between the United States and Russia has become a tedious ritual. The process also wastes valuable time that should be reserved for the future, not the past. Bold as the suggestion may seem, it might be time for both sides to accept that dealing with these grievances would be far more productive than complaining about them. Not every problem can be resolved, but attempting to minimize a problem’s ability to obstruct larger conversations is a worthy endeavor. For example, any substantive dialogue with Moscow is likely to be impeded by U.S. charges of Russian treaty violations, U.S. missile defenses and misperceptions about each other’s nuclear doctrines.

Treaty Violations

The United States has leveled a number of serious compliance charges against Russia over the years, from concerns to accusations of outright material breach. Those charges often elicited countercharges from Moscow. At this point, there are very few security treaties or agreements that are excluded from these accusations. That has led to a situation in the United States wherein critics of arms control efforts contend that there is no use in making agreements with Russia since violations would be sure to follow. While walking away from several treaties, including the INF and Open Skies, over cheating allegations, the Trump administration has also woven the idea that “treaties must be enforceable” into its talking points. Trump administration officials never defined exactly what “enforceable” means or would entail, but the punitive tone did not make dialogue with Russia any easier. While the Biden administration might take a different tone and approach, critics will continue to point to Russian treaty violations. There is no easy solution to this problem. Moscow denies every charge, even in the face of incredibly strong evidence, and the United States will not just ignore two decades of compliance determinations that outline an uncomfortable pattern. At a base level, the two parties can respectfully acknowledge the disagreements over compliance and endeavor to avoid the further erosion of existing agreements. That will not help with political critiques in the United States. In pursuing further agreements, the new White House will have to make the case that each agreement should be weighed on its own merits and contribution to security. The Kremlin, for its part, should conduct a clear-eyed review of why Russia keeps ending up on the receiving end of compliance accusations. If the two sides cannot better manage this, they might find that there are no more treaties over which to fight.

Missile Defense

Over the past few decades, both the Russians and the Americans have pursued missile defense programs, but it is the United States that has heavily invested in such systems at multiple ranges. Russia’s objections to the U.S. pursuit of a national missile defense system have resulted in diplomatic collateral damage.

Most important, the cycle of accusations, counteraccusations and the related development of weapons systems is quickly spinning the two countries into a full-fledged arms race. One could argue that the Russians have overblown the threat of missile defense: The U.S. national missile defense program, the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense system, is neither aimed at nor capable of intercepting Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles. U.S. officials argue that U.S. regional assets, like Aegis Ashore and THAAD, are limited in scale and ostensibly not aimed at Russian assets. Experts have undercut some of those arguments, demonstrating that some systems could have offensive capabilities. Further, Moscow clearly has an eye on the future of U.S. capabilities and did not miss the talk of “defending the U.S. homeland” against “the emerging threats” from Russia in the Trump administration’s 2019 Missile Defense Review. Indeed, increased investments in U.S. missile defenses have been perceived by Russia as an attempt to undermine its deterrent. In response, Russia has invested in increasing both the number and sophistication of delivery systems specifically designed to evade, overcome and defeat U.S. ballistic missile defenses. The new missile defense-evading delivery systems have prompted U.S. calls for increased spending on both offensive and defensive systems. The entire process makes it easy to understand why the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT), the first nuclear restraint agreement between the United States and the former Soviet Union, was coupled with the ABM Treaty.

It is clear that to move forward on strategic stability, both sides will have to figure out how to find middle ground on the issue of missile defense. Perhaps the first thing to do is once again agree to the fact that there is an inextricable connection between offensive and defensive weapons systems and that connection must be better managed.

If Washington wants both a limited missile defense program and an improved strategic stability with Moscow, it will need to take Russian concerns about threats to their deterrent seriously. Washington will also need to accept that, despite long efforts to change this reality, there is no such thing as complete invulnerability. Leaving the serious technical issues and political pressures aside, the United States would be well-advised to link missile defense investments to broader threat reduction efforts.

If Russia’s goal is a new treaty or agreement with the United States that limits missile defenses, Moscow should say so, but rehashing complaints about the ABM Treaty withdrawal does nothing to improve current security conditions. Russia will have to determine the level of U.S. missile defenses with which it would be comfortable, for example, systems intended to deal with smaller, distinct missile threats. Moscow could also agree to engage in sustained missile defense cooperation and transparency discussions with the United States.

Overall, both sides, despite ideological differences and distrust over these matters, should expand dialogue about the purpose and future of missile defense. That dialogue could also include dealing with missile proliferation around the world. After all, arms control agreements have intercepted and destroyed far more enemy missiles than any missile defense system has or could.

Misperceptions About Doctrine

The lack of truly substantive dialogue between the two countries has served to exacerbate misconceptions and misunderstandings about nuclear doctrines in the United States and Russia. Early in any serious bilateral nuclear risk reduction dialogue, it will be necessary to outline and address those possible misperceptions and misunderstandings. For example, the supposed Russian policy of E2D and recent U.S. investments in low-yield submarine-launched ballistic missiles will likely draw questions from the respective capitals. Relevant, high-ranking Trump administration officials publicly admitted that they had not discussed the E2D issue with their Russian counterparts. While quiet conversations may have transpired subsequently, the Biden administration should move to engage Russia in a more public discussion on E2D and broader nuclear doctrine matters. A broader discussion of how the United States (along with NATO) and Russia might find themselves in a conventional conflict is also overdue.

Reinvigorate Dialogue with New Topics

In addition to handling major disagreements, it will also be important for the United States and Russia to reinvigorate the substance of their dialogue. Topics can and should include new—and novel—delivery systems, tactical nuclear weapons, possible proliferant states, nuclear security cooperation, the weaponization of space, autonomous weapons systems with lethal capabilities, offensive cyber capabilities, additive manufacturing, unmanned aerial vehicles, artificial intelligence, precision-strike weapons and the blurring of the distinction between conventional and strategic systems. No relevant or applicable topic should be precluded, as all of these technologies will affect future stability. At the same time, neither side should insist on handling every topic at once.

As the two countries look to the future, it is also worth reviewing the structure and value of previous efforts to reduce tensions and the chance of conflict. (See Appendix 2.) In fact, the impressive volume of U.S.-Russian risk-reduction measures could provide ideas for dealing with strategic stability challenges in the 21st century.

It will also be necessary for both countries to exponentially increase current internal investments in future verification technologies that can help underpin future arms control, nonproliferation and nuclear security agreements. These investments will be necessary—because in order for parties to have confidence in new agreements they will need to have confidence in the verifiability of said agreements. Russia should also reassess its lack of participation in the International Partnership for Nuclear Disarmament Verification (IPNDV). The effort is producing positive results on both a diplomatic and practical level. Indeed, general cooperation with private industry and academia on verification technology development can yield useful contributions. No matter the origin, new, mutually acceptable technologies for warhead detection, continuous monitoring and remote sensing could enable the creation of an entirely new set of bilateral and multilateral agreements. While budgets will be tight in the wake of COVID-19, these investments would pay dividends. Of course, it is not just tools that are needed. New verification techniques will be necessary. Previous initiatives like the U.S.-Russia Joint Verification Experiment can serve as a guide for new technical cooperation projects.

Seeking Broader Cooperation

Beyond the big-ticket strategic issues, there are other security questions with which the United States and Russia must contend. For example, the United States will not get very far with Russia on nuclear risk-reduction efforts without addressing long-standing and new conventional threats, including those posed by dual-use technology and delivery systems. They will also have to deal with the fact that the agreements that have underpinned conventional security across the Euro-Atlantic region—the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty, the Vienna Document and the Open Skies Treaty—are coming apart at the seams. These agreements, along with accident-prevention agreements, are vital for preventing conventional conflicts that could escalate into nuclear ones. Both government and independent scholarship on the future of conventional arms control in Europe can provide a starting point for renewed dialogue. Trust deficits and disparate threat perceptions will have to be managed in such dialogues, so moving forward will require political will.

The United States can also push for more substantive activities in the P5 Process. This decade-old effort facilitates discussion between the five nuclear weapons states recognized by the NPT on the subject of their disarmament commitments under the agreement. Moving past dialogue and into distinct actions will require U.S. and Russian leadership. After all, China, France and the United Kingdom have not spent the last half century negotiating and implementing nuclear limitation and reduction agreements. Perhaps the P5 could look to the past for future inspiration. For example, the P5 could discuss the multilateralization of the 1973 Prevention of Nuclear War Agreement or the creation of more crisis communication tools. Overall, the group can draw lessons from the U.S.-Soviet Strategic Arms Limitation talks. Then-President Richard Nixon referred to SALT I as “the beginning of a process that is enormously important that will limit now and, we hope, later reduce the burden of arms, and thereby reduce the danger of war.” That seems as relevant a goal today as it was then. The venue could also provide an opportunity to start some critical conversations about global intermediate-range missile proliferation and the implications of non-nuclear strategic threats, like advanced biological weapons, on strategic stability. The United States and Russia could also challenge the P5 to engage in “preemptive” arms control, precluding concepts and actions that would have a deleterious effect on strategic stability before they are enacted.

Conclusion

The size and scope of the Russian nuclear arsenal and infrastructure present an existential threat to the United States. For that reason, Russia can and will continue to impact U.S. plans and policies regarding arms control, nonproliferation and nuclear security goals. Of course, there is no sense in mincing words: The United States does not trust Russia and it is easy to understand why. The feeling is undoubtedly mutual. Dealing with Moscow, especially in the wake of unprecedented cyberattacks directed at U.S. federal agencies, will be politically fraught for the new administration. That does not change the fact that the United States and Russia are still just a few bad decisions away from the end of the world. Scientific experts estimate that a U.S,-Russian nuclear exchange based on current understandings of force postures would result in more than 90 million casualties within hours, not to mention the longer-term damage to health, property and climate. That is why the United States can and should engage Russia to deal with immediate nuclear threats, while also working to enhance and expand dialogues on nuclear risks in a regularized fashion. It will also be necessary to assess and process both long-standing complaints and new and emerging challenges. (The latter category includes cyber threats, considered briefly in Appendix 3.)

There is no other rational course of action. As has been outlined by scholars in vivid detail, the United States was lucky to escape the Cold War without a nuclear conflagration. There is no guarantee that luck will last forever and the nuclear threat from Russia remains. If the reduction of nuclear dangers and the prevention of nuclear war is a priority for leaders in Washington, then partnering with Moscow is essential—and unavoidable.

Footnotes

- In the traditional sense, the concept of strategic stability referred to deterrence through the threat of mutually assured destruction. More recently, it has become a catch-all term for matters relating to U.S.-Russian force postures, nuclear doctrines and the state of bilateral arms control.

Alexandra Bell

Alexandra Bell is the senior policy director at the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation.

This report was made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Edited by Natasha Yefimova-Trilling and Simon Saradzhyan. Research contributed by Russia Matters student associate Anastasiia Posnova. Appendices compiled by RM staff.

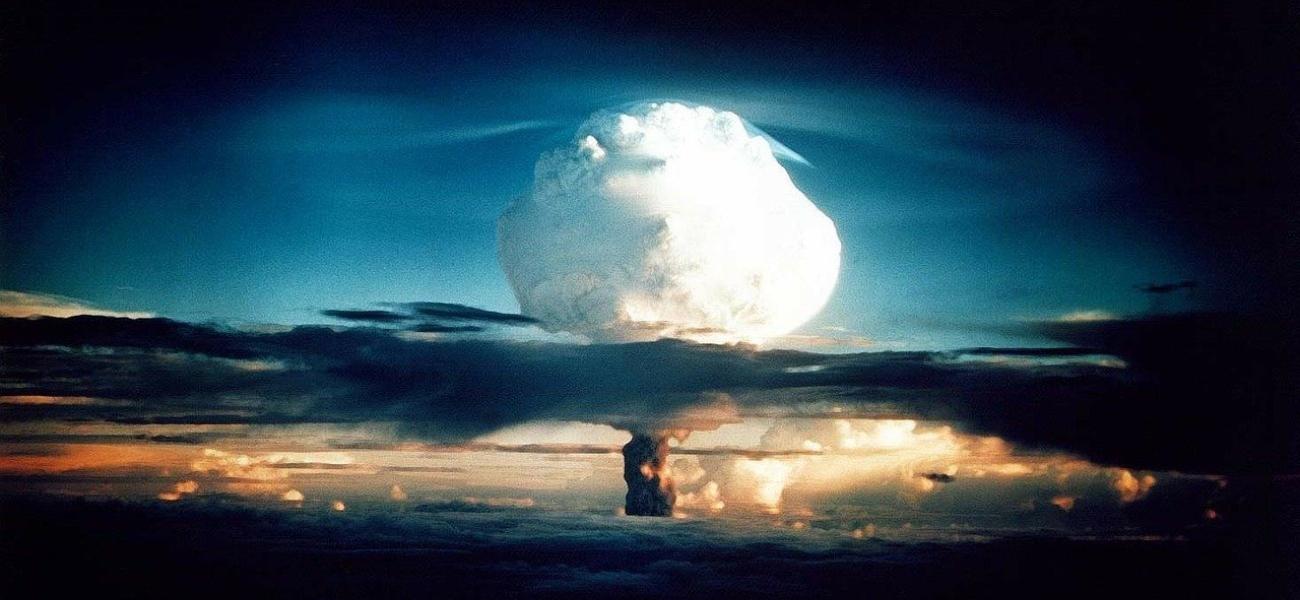

The opinions expressed in this primer are solely those of the author. Photo shared under a Pixabay license.

Appendix 1: Limited Nuclear Strikes, or ‘Escalate to Deescalate’

Both Russia and the United States keep open their options for using limited nuclear strikes to deescalate (that is, to end) and win conflicts. This fact highlights a dangerous problem that remains with us from Cold War days—the risk of a conventional conflict escalating into a nuclear war.

In January 2020, Kevin Ryan, a retired U.S. Army brigadier general and former defense attaché to Russia, published a paper with Russia Matters exploring whether Moscow indeed espouses a strategy of “escalate to deescalate”—essentially, a plan to use limited nuclear strikes in a conventional conflict to “shock an adversary into suing for peace.” U.S. military officials have believed since at least 2015 that this is the case and American policymakers have “already ordered the development of new weapon systems and capabilities to ensure Russia's plan cannot work against the United States,” Ryan wrote. “Russia's political leaders, however, say they don't have such a plan and that ‘escalate to deescalate’ doesn't exist in their doctrine at all.”

Since Russia’s war plans, like most countries’, are classified, Ryan tried to determine whether an “escalate to deescalate” policy exists by relying on “unclassified documents, professional articles and public statements.” He concluded that both Russia and the United States do consider “using nuclear strikes to deescalate (that is, to end) and win conflicts.” And although Moscow does not officially call this escalating to deescalate, the phrase has been useful insofar as it “has focused military experts, political leaders and the general public on a dangerous problem that remains with us from Cold War days—the risk of a conventional conflict escalating into a nuclear war.” Some details of Ryan’s argument are summarized below; the original paper includes a good list of suggested readings on the topic.

What Does the US Mean When Accusing Russia of an ‘Escalate to Deescalate’ Policy?

- The phrase “escalate to deescalate” first appeared in American briefings and documents, not Russian. While the term may mean different things to different people, Ryan’s paper uses a definition based on June 2015 congressional testimony by then-Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work and vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Adm. James Winnefeld (and essentially repeated in the Defense Department’s 2018 Nuclear Posture Review): A Russian strategy that seeks to deescalate (i.e., end) a conventional conflict through coercive threats including limited nuclear use.

- The idea behind "escalate to deescalate" is not at all new or unique to Russia. As Jay Ross, a U.S. Army Reserve nuclear weapons officer, wrote in an April 2018 article, the strategy’s conceptual underpinnings follow from seminal books by Harvard professor Thomas Schelling and were “part of the American strategy lexicon until the end of the Cold War."

- The concept of using nuclear weapons to manage the escalation or deescalation of a conflict was a very real strategy used by both Russia and the U.S. during the Cold War. And it remains a part of American nuclear strategy today. Department of Defense 2019 Joint Publication 3-72, Nuclear Operations, says: "Employment of nuclear weapons can radically alter or accelerate the course of a campaign. A nuclear weapon could be brought into the campaign as a result of perceived failure in a conventional campaign, potential loss of control or regime, or to escalate the conflict to sue for peace on more favorable terms."

Russian Denial of ‘Escalate to Deescalate’

- Russian policy makers acknowledge that they think about using a nuclear weapon to deescalate a conflict, but with a caveat: From the president to the official military doctrine, Moscow’s stated position has been that Russia might use a nuclear weapon first only if the survival of the Russian state were at risk.

- President Vladimir Putin reiterated this point in October 2018: "In our concept of nuclear weapons use there is no preemptive strike… Our concept is a retaliatory-offensive strike [otvetno-vstrechny udar].1 … This means we are prepared to, and will use, nuclear weapons only when we are convinced that someone, a potential aggressor, is attacking Russia, our territory."

- Putin and other Russian officials point to their public strategic doctrine documents to support their claims, emphasizing that the phrase “escalate to deescalate” is not there. Doing so is, frankly, pointless: In Russian parlance, military doctrines are not intended as "how we fight" manuals, and how Russian leaders might employ nuclear weapons would not be part of these doctrinal documents.

Examining the Evidence for ‘Escalate to Deescalate’

- While Russia, like most countries, classifies its plans for military operations, professional articles and papers on the subject strongly support the contention that Russian nuclear thinking includes using limited nuclear strikes to deescalate a conflict, even in cases where the survival of the Russian state is not at risk.

- Russian nuclear experts have been debating how to use the Russian nuclear arsenal to guarantee the country’s security since at least the late 1990s, when Russia was in economic and military free fall.

- One of the first people to describe this debate to Westerners, in a 1998 report, was Nikolai Sokov, a former Russian Foreign Ministry officer—and Soviet negotiator for START I and II—turned American citizen. "Overall,” he wrote, “the perception of an imminent threat [to Russia] has created a host of (still rather poorly developed) theories analogous to American doctrines of limited nuclear strike, flexible response, limited war, escalation dominance, etc. The purpose is to enable nuclear weapons to achieve a broad variety of missions when less than survival of the country is at stake.”

- The vigorous brainstorming described by Sokov continued after his paper was published. In 1999, a senior Russian missile troops and artillery officer and two co-authors wrote an article suggesting that nonstrategic nuclear weapons—smaller-yield weapons used on the battlefield—could be used in a phased approach to intimidate an adversary while the threat of using strategic nuclear weapons—longer-range weapons aimed at the adversary's homeland—would deter the opponent from further escalation.

- Discussions about the possible uses of nuclear weapons took place among Russia's academic, legislative and civilian defense experts as well. Again, Russia's poor economic and conventional military condition, and the threat posed by NATO, loomed large in their thinking.

- Writing in 2000, Alexei Arbatov, a Russian scholar who was deputy chairman of the State Duma’s Defense Committee at the time, described the new role nuclear weapons had to play, reflecting the views of the security establishment and arms negotiation community: "Just as NATO employed a nuclear first-use strategic concept during the decades after 1945 (when NATO needed to emphasize its nuclear forces in order to offset its conventional force vulnerabilities), Russia has chosen the same strategy. Since 1993, it has adopted a nuclear first-use strategic concept in order to deemphasize the weaknesses in its conventional military forces."

- In a separate 2008 paper, Arbatov added to his thinking, writing that in certain situations "Russia may decide to selectively initiate the use of nuclear weapons to ‘deescalate an aggression’ or to ‘demonstrate resolve,’ as well as to respond to a conventional attack on its nuclear forces, command, control, communications and intelligence (C3I) forces (including satellites), atomic power plants and other nuclear targets.” (The term "demonstrate resolve" might prompt accusations that Arbatov is opening the door for a preemptive use of nuclear weapons; but, taken together with Arbatov's numerous other writings, in which he repeatedly sees Russian nuclear use only in response to aggression, it seems unlikely he intended this to be an exception.)

- Russian military experts have advocated investing in the development of a better conventional force. However, as recently as 2015, two colonels writing in the elite Defense Ministry journal "Military Thought" contended that “not enough attention is being paid" to the creation of adequate conventional capabilities and Russia must, therefore, continue to rely on nuclear forces to provide the necessary escalation to convince an adversary like the U.S. or NATO to end operations. The authors, furthermore, advocated the earliest possible use of a nuclear retaliatory-offensive strike in the event of a conflict—within minutes of an aggressor's attack.

- While Russian military writing provides a clear indication that "escalate to deescalate" is an existing concept in Russian nuclear thinking, an examination of Russia's military exercises provides a less clear answer. Western analysts make a good case that Russian forces do practice the use of tactical nuclear weapons in their large-scale combined arms exercises (perhaps more than half a dozen times since such exercises resumed in 1999), but it is not clear from the evidence that they practice using those weapons for the narrow purpose of "escalating to deescalate"—namely to end a conflict.

Does ‘Escalate to Deescalate’ Include Preemptive or Preventive Strikes?2

- Although some military thinkers—including the authors of the 2015 “Military Thought” article mentioned above—have supported preemptive or preventive strikes, and despite some Russian press reports that missile units have practiced preemptive strikes (uprezhdayuschy udar), senior government officials have uniformly maintained that they do not advocate those kinds of nuclear strikes.

- One notable exception may be Nikolai Patrushev, who has been the secretary of Russia’s National Security Council for over a decade. In October 2009, as a new military doctrine was being finalized, he informed an Izvestia newspaper reporter that the forthcoming doctrine would allow for Russia to launch preemptive nuclear strikes: "There are a variety of prospects for using nuclear weapons depending on the situation and intentions of the likely adversary. In situations critical for national security, a preemptive (preventive) nuclear strike against an aggressor is not excluded."

- Ultimately, preemptive and preventive nuclear strikes were not part of the 2010 military doctrine (or of the latest 2014 version), at least not in the unclassified portions. It is not clear whether Patrushev’s comments revealed something from the doctrine's classified nuclear annex or reflected an internal debate among security elites, which was still ongoing five years later.

- In his 1998 article, Sokov observed that Russian policies about using nuclear weapons, either in a first or a retaliatory strike, could be intentionally vague: "After all, if there exists even a miniscule chance of escalation to the nuclear level, no NATO country would think about challenging Russia; at least this follows from a Schelling-like analysis which is popular in Russia."

In short, we cannot be sure whether Russia's understanding of "escalate to deescalate" includes preemptive or preventive nuclear strikes. Patrushev suggested yes; Putin suggested no. The reader must decide.

Footnotes

- Another English term sometimes used to translate “otvetno-vstrechny udar” is “retaliatory counterstrike.”

- Translators use both "preemptive" and "preventive" to translate the Russian word "preventivny." In American military terminology there is a distinction: "Preventive" strikes occur before any threat is imminent and "preemptive" strikes occur on the eve of an attack by an adversary. In his October 2018 comments Putin was saying that neither kind of strike is part of Russian nuclear doctrine. (A second Russian term sometimes translated as “preemptive” is “uprezhdayuschy.”)

Appendix 2: Agreements That Help Russia and US Not Stumble Into War

Apart from arms control treaties, the U.S. and Russia have more than a dozen bilateral agreements meant either to prevent military incidents and accidents or to build confidence between the countries’ governments and militaries. While not perfect, they have helped ensure against an “accidental war” between the two nuclear superpowers. According to Russia Matters founding director Simon Saradzhyan, Washington and its NATO allies should consider developing a unified position in order to approach Moscow about formal negotiations on ways to multilateralize some of the existing bilateral U.S.-Russia agreements; Russian and Western leaders should also make sure their military commanders do not take actions that increase the risk of unintended conflict.

During the Cold War, a handful of extremely tense incidents—most notably the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 and the Able Archer exercises of 1983—brought the U.S. and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war. To stave off catastrophe, Washington and Moscow have concluded more than a dozen bilateral agreements, plus some that are multilateral, which have helped them avoid a “hot war” over the past 80 years. These include deals both to prevent unintended military incidents and to build confidence. Earlier this year, Russia Matters founding director Simon Saradzhyan took a systematic look at the documents in question and at steps that could be taken to further enhance such safeguards; this section summarizes his findings, including an expanded list of key agreements.

In particular, Saradzhyan argued, the U.S. and its NATO allies should work toward a unified position that would help them approach Russia about multilateralizing some of the most significant U.S.-Russian agreements, thereby reducing the chance of “accidental war” between Moscow and the alliance. Currently, Russia’s agreements on preventing dangerous military incidents cover some NATO members but not others. For example, some alliance members—including the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Norway, Spain, the Netherlands, Canada, Greece and Portugal—have agreements with Russia similar to the 1972 U.S.-Soviet Agreement on Prevention of Incidents on and Over the High Seas, and Canada and Greece also have agreements with Russia akin to the 1989 U.S.-Soviet Agreement on Prevention of Dangerous Military Activities; however, almost a dozen NATO member states have no such agreements with Moscow, even when they abut seas. These include Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Slovenia. Nor are there any multilateral NATO-Russia (or NATO-Collective Security Treaty Organization) agreements on preventing dangerous military incidents, although a NATO-Russia memorandum of understanding on avoiding and managing such incidents has been discussed in Track 2.

The 1989 agreement on preventing dangerous military activities—which one Harvard scholar called a “watershed” in Soviet-American military relations—is particularly worth multilateralizing, in Saradzhyan’s view. NATO and Russia could discuss including concrete mechanisms for preventing incidents in such existing multilateral agreements as the 2011 Vienna Document and the Convention on International Civil Aviation, including, perhaps, a requirement for warplanes to fly with their transponders turned on at all times while in international airspace.1 The U.S. and its NATO allies should also, of course, discuss options for managing the aftermath of the collapse of the Open Skies Treaty of 1992, which the U.S. and Russia have both recently abandoned.

In addition to enhancing the legal framework for preventing dangerous incidents, Russian and Western leaders should make sure their military commanders do not take actions that increase the risk of an unintended conflict, according to Saradzhyan.

Last but not least, the sides should seriously consider how to prevent incidents with potentially dangerous consequences in a domain that did not exist during the Cold War: cyber. Now that the U.S. and Russia both have cyber troops—not to mention the role of computer technologies across the military more broadly, including in command and control—miscalculations in this domain could lead to an accidental war and should be prevented at all costs.

I. Agreements on preventing military incidents and accidents

I.A. Bilateral U.S.-Russian agreements on preventing military incidents and accidents

Highlights:

- The hotline system is located at the Pentagon’s National Military Command Center and was first used by the U.S. and Russia in 1967 during the Six-Day War.

- Since its establishment, the hotline has undergone multiple technological upgrades; it is reportedly tested once an hour by operators on both sides.

- The hotline is meant to avoid war; U.S. President Barack Obama used it in October 2016 to warn Putin against using hackers to disrupt the U.S. election.

Operational status: Remains in force.

Contents include:

- A pledge by both parties to take measures each considers necessary to maintain and improve its organizational and technical safeguards against accidental or unauthorized use of nuclear weapons;

- Arrangements for immediate notification should a risk of nuclear war arise from such incidents, from detection of unidentified objects on early warning systems or from any accidental, unauthorized or other unexplained incident involving a possible detonation of a nuclear weapon;

- Advance notification of any planned missile launches beyond the territory of the launching party and in the direction of the other party.

Operational status: Remains in force.

I.A.3. U.S.-Soviet Agreement on Prevention of Incidents on and over the High Seas, 1972

Contents include:

- Not interfering in the "formations" of the other party;

- Avoiding maneuvers in areas of heavy sea traffic;

- Requiring surveillance ships to maintain a safe distance from the object of investigation so as to avoid "embarrassing or endangering the ships under surveillance";

- Using accepted international signals when ships maneuver near one another;

- Not simulating attacks at, launching objects toward or illuminating the bridges of the other party’s ships;

- Informing vessels when submarines are exercising near them;

- Requiring aircraft commanders to use the greatest caution and prudence in approaching aircraft and ships of the other party.

Operational status: Remains in force.

I.A.4. U.S.-Soviet Agreement on the Prevention of Nuclear War, 1973

Contents include: Agreement by the signatories that:

- “An objective of their policies is to remove the danger of nuclear war and of the use of nuclear weapons”;

- They “will refrain from the threat or use of force against” each other;

- “If at any time relations … involve the risk of a nuclear conflict," then they "will immediately enter into urgent consultations with each other and make every effort to avert this risk."

Operational status: Remains in force (“of unlimited duration”).

I.A.5. U.S.-Soviet agreement on prevention of dangerous military activities, 1989

Contents include: “Each Party shall take necessary measures directed toward preventing dangerous military activities, which are the following activities of personnel and equipment of its armed forces when operating in proximity to personnel and equipment of the armed forces of the other Party during peacetime:

- “Entering by personnel and equipment of the armed forces of one Party into the national territory of the other Party owing to circumstance brought about by force majeure, or as a result of unintentional actions by such personnel…

- “Interfering with command and control networks in a manner which could cause harm to personnel or damage to equipment of the armed forces of the other Party.

- “Hampering the activities of the personnel and equipment of the armed forces of the other Party in a Special Caution Area2 in a manner which could cause harm to personnel or damage to equipment;”

- The agreement covers not only personnel but also “any ship, aircraft or ground hardware of the armed forces of the Parties.”

Operational status: Remains in force.

I.A.6. Moscow Declaration by U.S. President Bill Clinton and Russian President Boris Yeltsin, 1994

Contents include:

- “The presidents announced that they would direct the detargeting of strategic nuclear missiles under their respective commands so that by not later than May 30, 1994, those missiles will not be targeted. Thus, for the first time in nearly half a century—virtually since the dawn of the nuclear age—the United States and Russia will not operate nuclear forces, day-to-day, in a manner that presumes they are adversaries.”

Operational status: Unclear.

I.A.7. U.S.-Russia memorandum on safety of flights in Syria, 20153

Contents include:

- Specific safety protocols for aircrews to follow, including maintaining professional airmanship at all times and the use of specific communication frequencies;

- Provisions for the creation of a ground communications link (established) between the two sides in the event air communications fail;

- Provisions for the formation of a working group to discuss any implementation issues;

- Covers coalition aircraft;

- The U.S. has also told Russia where its special forces are in Syria so that Russia would not bomb them.

Operational status: Remains in force.

I.A.8. U.S.-Russian agreement of early November 2017 on dividing line in Syria.

- U.S. and Russian officers reportedly agreed on the Euphrates River as a dividing line in Syria and on a system of advance notifications prior to any river crossings.

Operational status: Unclear.

I.B. Multilateral agreements on prevention of military accidents and incidents

I.B.1. International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972

Signatories include: U.S., Russia, China

Contents include:

- Every vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision;

- Every vessel shall at all times proceed at a safe speed so that she can take proper and effective action to avoid collision and be stopped within a distance appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions;

- Every vessel shall use all available means appropriate to the prevailing circumstances and conditions to determine if risk of collision exists;

- When two power-driven vessels are meeting on reciprocal or nearly reciprocal courses so as to involve risk of collision each shall alter her course to starboard so that each shall pass on the port side of the other;

- When two power-driven vessels are crossing so as to involve risk of collision, the vessel which has the other on her own starboard side shall keep out of the way and shall, if the circumstances of the case admit, avoid crossing ahead of the other vessel;

- A vessel restricted in her ability to maneuver when engaged in an operation for the maintenance of safety of navigation in a traffic separation scheme is exempted from complying with the Rule [on traffic separation schemes] to the extent necessary to carry out the operation.

Operational status: Remains in force.

I.B.2. Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, 2014

Signatories include: Australia, Brunei, Cambodia, Canada, Chile, China, France, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Peru, the Philippines, Russia, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, Tonga, the United States and Vietnam

Contents include:

- Calls for naval warships and planes to maintain a safe separation between vessels;

- When conducting exercises with submarines, surface naval ships should consider the display of appropriate signals to indicate the presence of submarines;

- Naval ships should generally avoid the simulation of attacks, discharge of signal rockets and weapons, illumination of navigation bridges and aircraft cockpits, aerobatics and simulated attacks in the vicinity of ships encountered;

- Does not apply to coastguards.

Operational status: Remains in force but is non-binding.

II. Confidence-Building Measures

II.A. Bilateral Confidence-Building Measures

II.A.1. U.S.-Soviet Agreement on the Establishment of Nuclear Risk Reduction Centers, 1987

Highlights include:

- Each party agreed to establish a Nuclear Risk Reduction Center in its capital and to establish a special facsimile communications link between these centers;

- The centers are intended to supplement existing means of communication and provide direct, reliable, high-speed systems for the transmission of notifications and communications at the government-to-government level;

- The NRRCs do not replace normal diplomatic channels of communication or the "Hot Line," nor are they intended to have a crisis management role;

- Today the U.S. NRRC handles information exchange required by 13 arms control treaties and security-building agreements between the United States and more than 55 foreign governments and international organizations.

Operational status: Remains in force.

Contents: Provides for notification, no less than 24 hours in advance, of the planned date, launch area and area of impact for any launch of an ICBM or SLBM. The agreement says these notifications be provided through the Nuclear Risk Reduction Centers.

II.A.3. U.S.-Soviet Agreement on Reciprocal Advance Notification of Major Strategic Exercises (MSE), 1989

Contents: The agreement provides for each party to give the other advance notification of one major strategic-forces exercise that includes the participation of heavy bombers each year.

Operational status: Remains in force.

II.A.4. U.S.-Russian Arms Control and International Security Working Group, 2009

Highlights: Established under the auspices of the U.S.-Russia Bilateral Presidential Commission, the working group was to address 21st-century challenges including:

- Enhancing stability and transparency;

- Cooperating on missile defense;

- Preventing the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction;

- Assessing common threats.

Operational status: Suspended in the wake of the Ukraine crisis.

Highlights: A White House fact sheet’s section on “ICT Confidence-Building Measures” says:

- “The United States and the Russian Federation have also concluded a range of steps designed to increase transparency and reduce the possibility that a misunderstood cyber incident could create instability or a crisis in our bilateral relationship.”

- “To facilitate the regular exchange of practical technical information on cybersecurity risks to critical systems, we are arranging for the sharing of threat indicators between the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) … and its counterpart in Russia.”

- “We decided to use the longstanding Nuclear Risk Reduction Center (NRRC) links established in 1987 between the United States and the former Soviet Union to build confidence between our two nations through information exchange, employing their around-the-clock staffing at the Department of State in Washington, D.C., and the Ministry of Defense in Moscow.”

Operational status: Suspended in the wake of the Ukraine crisis.

II.B. Multilateral Confidence-Building Measures

II.B.1. Conventional Armed Forces in Europe (CFE) Treaty, 1992 (adapted in 1999 to reflect disbanding of Warsaw Pact)

Contents include:

- Setting equal limits on the number of tanks, armored combat vehicles, heavy artillery, combat aircraft and attack helicopters that NATO countries and then-Warsaw Pact members could deploy between the Atlantic Ocean and the Ural Mountains;

- Setting regional (flank) limits intended to prevent destabilizing force concentrations of ground equipment.

Operational status: Russia “suspended” its participation in 2007, citing the ongoing delay of the adapted treaty’s entry into force among some of the signatories.

II.B.2. Open Skies Treaty, 1992 (entered into force in 2002)

Contents include:

- Permitting each state-party to conduct short-notice, unarmed reconnaissance flights over the others' entire territories to collect data on military forces and activities.

Operational status: The U.S. withdrew from the treaty in November 2020; Russia in January 2021 announced its intention to follow suit.

II.B.3. NATO-Russia Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security, 1997

Contents include: Statements that, in building their relationship, NATO and Russia will aim for:

- Enhanced regional air traffic safety, increased air traffic capacity and reciprocal exchanges, as appropriate, to promote confidence through increased measures of transparency and exchanges of information in relation to air defense and related aspects of airspace management/control;

- Increasing transparency, predictability and mutual confidence regarding the size and roles of the conventional forces of member states of NATO and Russia.

- Also states that NATO reiterates that, in the current and foreseeable security environment, the alliance will carry out its collective defense and other missions by ensuring the necessary interoperability, integration and capability for reinforcement rather than by additional permanent stationing of substantial combat forces.

Operational status: Remains in force but is non-binding.

II.B.4. Vienna Document on Confidence- and Security-Building Measures, 2011 (OSCE)

Highlights:

- Annual exchange of military information about forces located in Europe (defined as the Atlantic to the Urals);

- Notifications for risk reduction including consultation about unusual military activities and hazardous incidents;

- Prior notification and observation of certain military activities, such as large-scale exercises;

- Compliance and verification by inspection and evaluation visits.

Operational status: Remains in force; however, the U.S. has accused Russia of “incomplete implementation” and attempts “to evade existing reporting requirements.

Footnotes

- At the NATO-Russia Council meeting of July 13, 2016, Russian diplomats reportedly offered a new plan that would commit Russian and all other planes flying over the Baltic Sea to switch on their transponders, a step that helps civil aviation authorities track flights and avoid near misses. More recently, in September 2019, U.S. Air Forces in Europe commander Gen. Jeffrey Harrigian said that a direct line of communication between NATO air commanders and their Russian counterparts could be helpful in deescalating tensions.

- “‘Special Caution Area’ means a region, designated mutually by the Parties, in which personnel and equipment of their armed forces are present and, due to circumstances in the region, in which special measures shall be undertaken in accordance with this Agreement.”

- Pentagon spokesman Peter Cook said the full text of the memo would not be released at Russia’s request, according to Reuters; Army Gen. Lloyd Austin, the head of U.S. Central Command, signed the protocol on the U.S. side.

Appendix 3: Cyber Risks to Nuclear Command and Control Systems

While this primer does not focus specifically on the role of cyber means in preventing (or encouraging) nuclear war, there can be no doubt that information and communications technologies serve vital functions in the nuclear field and are worthy of separate consideration. One particularly sensitive topic for further discussion is cyber risks to nuclear command and control systems (NC3), sometimes also called nuclear C3I for “command, control, communication and information.” This appendix summarizes some recent thinking on the topic; it is far from exhaustive.

“The New Synergy Between Arms Control and Nuclear Command and Control,” Geoffrey Forden, Nuclear Threat Initiative, February 2020. Forden is a physicist and principal member of the technical staff at the Cooperative Monitoring Center at Sandia National Laboratories.

Summary: “There are renewed worries that the U.S. NC3 might be attacked with cyberweapons, potentially triggering a war. These concerns have been present since at least 1972 when the Air Force Computer Security Technology Planning Study Panel found that the ‘current systems provide no protection [against] a malicious user.’ … NC3 system components of the United States and other nations become potential targets for adversaries during and immediately prior to war. One systematic way of thinking about these threats describes them by three general threat categories: misinformation introduced to the nuclear ‘infosphere’ that might make command authorities unaware of a nuclear attack or believe there is one when there is not; cyberattacks intended to disable or destroy nuclear weapons, preventing them from being launched when the national authority wants them to be launched; and cyberattacks intended to launch nuclear weapons under false circumstances, such as issuing counterfeit launch orders. … Some of these attacks, particularly planting misinformation into the nuclear infosphere, are more relevant for national command centers than the nuclear weapons themselves. As an illustration of a cyberattack in the misinformation category, a cyberattack on an air defense system intercepted signals sent from the radar to the command center and prevented the controllers from even knowing there was an attack underway. Others could be aimed at the launch systems themselves. It is these later cases where embedded NC3 becomes most important. If the warheads themselves generate public/private encryption keys and do not share the private key with other elements of the nuclear enterprise, the cybersecurity of launch control can be greatly enhanced. Not doing so continues to leave the command system for launching nuclear weapons susceptible to a number of cyberattacks that have been known to jump even ‘air gaps’ such as those separating NC3 networks from the public internet. … Moving verification of the president’s launch orders into the weapon itself can be thought of as embedding NC3 into the nuclear weapon and conversely integrating the weapon into the NC3 architecture. … In the context of NC3, enabling nuclear weapons to create their own encryption keys with PUF-based devices provides a considerable number of advantages. First, the weapon provides its own private encryption key that does not have to be stored elsewhere. Second, the same unique private encryption key is generated each time it is needed and hence cannot be accessed at other times by unauthorized users. Third, this concept mitigates the danger of a malicious insider or a foreign or terrorist actor launching or preventing the launch of U.S. nuclear weapons even if they have gained access to the NC3 system. Fourth, this concept imposes no barriers to tailoring deterrence. Finally, this solution can be implemented and still have a human in the loop before launch.”

“Cybersecurity of NATO’s Space-Based Strategic Assets, Beyza Unal, Chatham House, July 2019. Unal is a senior research fellow with the International Security Program at Chatham House, specializing in nuclear policy, cybersecurity, space security and NATO defense and security policy. She formerly worked in the Strategic Analysis Branch at NATO Allied Command and Transformation.

The author discusses cyber threats to space-based components of command-and-control systems, writing that intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance satellites, a key component of conventional and nuclear targeting and command, are “vulnerable to cyberattacks. Sensors could also be manipulated through physical or cyber means.”

“Nuclear Weapons in the New Cyber Age,” Page O. Stoutland, Samantha Pitts-Kiefer, Nuclear Threat Initiative, September 2018. Stoutland is NTI’s vice president for scientific and technical affairs; Pitts- Kiefer is director of NTI’s Global Nuclear Policy Program.