Opportunity for Diplomacy: No Russian Attack Before Feb. 20

This article was originally published by The National Interest, with the subheading: "Most of the American foreign policy community has still not come to grips with the relationship that has developed between Russia and China in the decade since Xi Jinping became president."

Last Wednesday, Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman stated publicly that “we certainly see every indication that [Vladimir] Putin is going to use military force sometime, perhaps between now and the middle of February.” While I have great respect for the deputy secretary (whom I’m proud to count as a friend), I disagree. She, of course, is reading highly classified intelligence that I don’t have access to. Nonetheless, watching all the evidence I can see, I’ll state my high-confidence judgment that Putin will not use military force against Ukraine before February 20.

To sharpen the point, in a conversation last week with a colleague serving in the current administration, I offered him a four-to-one bet against Putin invading Ukraine before February 20. That means I bet $4 of my money against $1 of his that Russia will not invade before February 20. A willingness to give four-to-one odds reflects a high degree of confidence in one’s forecast: 80 percent. For comparison, at betting sites like PredictIt, the odds today of Republicans winning control of the House of Representatives in the November midterm election are four-to-one. Despite press announcements of Boris Johnson’s imminent demise, PredictIt also estimates the odds of him staying in office through February to be roughly four-to-one.

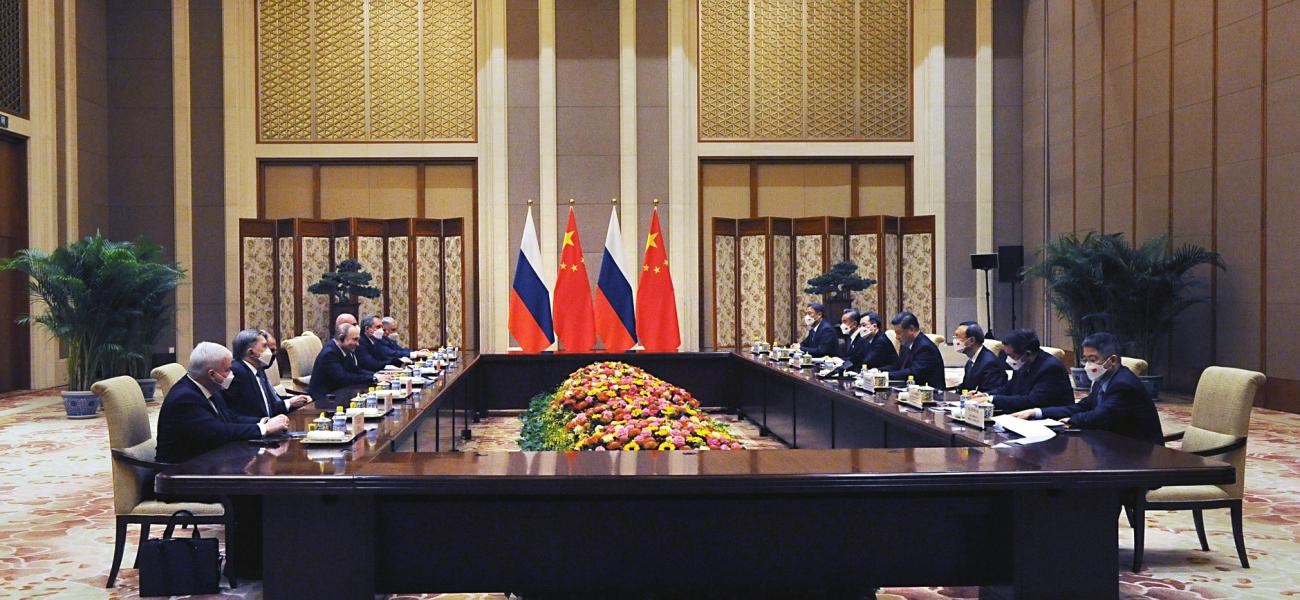

My confidence about the next two weeks providing a window of opportunity for diplomacy is based on my assessment of Putin’s respect for Xi Jinping and the fact that the Beijing Olympics run from today until the closing ceremony on February 20. Xi has promised that these Winter Olympics will be, in his words, “spectacular.” In the theater he has constructed, the billion expected viewers will see China’s great leaps forward, particularly in technology, in the decade and a half since Beijing hosted the summer Olympics in 2008. Xi’s most honored international guest at the opening ceremony will be Putin. Putin will be the first world leader to be granted an in-person meeting with Xi in nearly two years. Can one imagine Putin choosing to rain on the parade of his nation’s closest foreign ally and the leader whom he has called his “best buddy?” No way. (Parenthetically, this is a useful reminder that leaders of countries are also human beings. Personal relationships matter. Watch the body language in Beijing.)

Most of the American foreign policy community has still not come to grips with the relationship that has developed between Russia and China in the decade since Xi became president. Former Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis expressed the consensus of the U.S. strategic community when he called such an alignment a “natural nonconvergence of interests.” All the structural factors on the geopolitical chessboard tilt against it. Large swaths of what was for most of the past 1,000 years China are now part of Russia’s eastern territories. On Chinese maps, including the wall map at the Ministry of Defense in Beijing, Russia’s major Pacific port at Vladivostok is still called by its Chinese name, Haishenwai. Russia is geographically the largest nation in the world, China the most populous. And on and on.

Nonetheless, as the January 2019 cover story in this magazine explained three years ago, it is past time that the American strategic community wake up to what is nothing less than a “functional Sino-Russian alliance.” The major factor in creating this alignment has been Xi’s artful diplomacy in courting Putin: giving him the respect Putin’s conception of Russia as a great power requires, and that he personally craves. But Xi’s effort has gotten a major assist from myopic, often misguided American diplomacy as it has toggled back and forth between attempting to stigmatize and isolate Moscow one week and Beijing the next.

The big question posed by the 2019 article was: is China’s relationship with Russia more operationally consequential than the U.S. relationship with most of its treaty allies? The answer was: yes, and as a specific case in point, I argued, that it is more operationally significant than the U.S. relationship with India.

Unfortunately, students of diplomacy have not given us a scorecard for assessing alliances. Lacking that, consider the relationship between China and Russia on seven dimensions: threat perceptions, relationship between leaders, official designation of the other, military and intelligence cooperation, economic entanglement, diplomatic coordination, and elites’ orientation.

When Russian or Chinese national security leaders think about current threats, the specter they see is the United States of America. They believe the United States is not only challenging their interests in Eastern Europe or the South China Sea, but actively seeking to undermine their authoritarian regimes. Indeed, Putin and Xi reportedly compare notes about the ways Washington is working to weaken each leader’s control within his own society and even topple him.

In contrast with Barack Obama’s visceral disdain for Putin and Donald Trump’s charge that China is “raping America,” Xi has persuaded Putin that they are “best friends.” To which capital did Xi take his first trip after becoming president? Moscow. Which foreign leader is invited to speak immediately after Xi at every international meeting China hosts? Putin. As Putin noted in 2018, the only leader in the world with whom he had ever celebrated his birthday is Xi. In awarding Putin China’s “Medal of Friendship,” Xi called the Russian president his “best, most intimate friend.” Xi and Putin have met thirty-seven times, which is almost twice as often as either has met with any other foreign leader.

Official U.S. national security documents designate Russia and China as America’s “strategic competitors,” “strategic adversaries,” and even “enemies.” Often, they are discussed in the same sentence, as if they were twins. According to the Trump National Security Strategy: “China and Russia challenge American power, influence, and interests, attempting to erode American security and prosperity.” Both are accused of conducting major “influence operations” against the United States and interfering in U.S. elections.

By contrast, Chinese and Russian national security documents call their relationship a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” According to Xi, this is “the world’s most important bilateral relationship, and is the best relationship between large countries.” As China’s former ambassador to Russia, Li Hui, put it, “China and Russia are together now like lips and teeth.” The words used by Russia’s Foreign Ministry are “comprehensive, equal, and trust-based partnership and strategic cooperation.” Even alpha male Putin has found an acceptable way to recognize publicly Russia’s junior role in this partnership, saying “the main struggle, which is now underway, is that for global leadership and we are not going to contest China on this.”

Most American experts discount Sino-Russian military cooperation. Commenting on an unprecedented 2018 military exercise in which 3,000 Chinese soldiers joined 300,000 Russians in practicing scenarios for conflict with NATO in Eastern Europe, Mattis said: “I see little in the long term that aligns Russia and China.” Fortunately, today defense planners are watching more carefully. Russian and Chinese general staffs now have candid, detailed discussions about the threat U.S. nuclear modernization and missile defenses pose to each of their strategic deterrents. For decades, in selling arms to China, Russia was careful to withhold its most advanced technologies. No longer. In recent years it has not only sold China its most advanced air defense system, the S-400, but has actively engaged with China in joint research and development on rockets engines—and unmanned aerial vehicles. Putin also announced that Russia is helping China develop missile attack warning systems that, in his words, “will dramatically increase China’s defense capability because only the U.S. and Russia have such a system now.” Joint military exercises by their navies in the Mediterranean Sea, the South China Sea, and the Baltic Sea compare favorably with U.S.-Indian military exercises. As a Chinese colleague observed candidly, if the United States found itself in a conflict with China in the South China Sea, what should it expect Putin might do in the Baltics? Or if the United States should stumble into a military conflict with Russia over Ukraine?

In their diplomacy, Russia and China mirror the relationship between the two leaders. On major international issues, they coordinate their positions. For example, when voting in the United Nations Security Council, they agree 98 percent of the time according to a 2018 count. Russia has backed every Chinese veto since 2007. The two have worked together to create and strengthen new organizations, including the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS, to rival traditional American-led international organizations.

Economically, Russia is slowly but surely pivoting east. China has displaced the United States and Germany as trade between the two countries doubled since 2015 and China became Moscow’s number one trading partner. Today, China is the top buyer of Russian crude oil, importing almost four times the amount of oil Germany buys. Completion of the Power of Siberia pipeline in 2019 and prospects of a further pipeline provide another outlet for gas to flow to China instead of Europe—if Europeans were to decide to buy less or Moscow chose to favor Chinese markets. After Trump targeted Huawei and banned exports of advanced semiconductors, Putin condemned America’s campaign as the “first technological war of the coming digital era.” Huawei announced plans to quadruple its research and development staff in Russia, and Putin signed a decree calling 2020 and 2021 the years of “Russian-Chinese Scientific, Technical, and Innovation Cooperation.”

After Russia seized Crimea from Ukraine in 2014, when the United States imposed sanctions aimed at limiting Russia’s access to global financial markets and restricted its trade regime, China had its back. It signed a three-year currency swap deal worth $25 billion that gave Russia access to currency it could use for trade without violating U.S. restrictions. That same year, it also signed a $400 billion gas deal. In defiance of America’s global embargo on Iranian oil, Russia imported Iranian oil to sell onto international markets, including China.

Meanwhile, Russian elites continue to look West. They are predominantly European in their culture, history, religion, and dreams. Wealthy Russians buy second (and third) luxury homes in London, New York, and on the French Riviera. They speak English and travel to Paris, New York, or London to shop. Many have children who live in the West. Cultural change is hard, and slow. But oligarchs who now find themselves the targets of sanctions that prevent them from doing business in the United States are exploring alternatives. And some of Russia’s leading thinkers are changing their tune. The Honorary Chairman of Russia’s Council on Foreign and Defense Policy Sergey Karaganov maintains that “the ‘westernizer’ today is a thing of the past. Those looking forward to the future most show interest in the East.” In 2021, surveys showed that 39 percent of Russians held a positive view of the United States, while 74 percent of Russians held a positive view of China. When asked who their “greatest enemies” are, 60 percent of Russians pointed to the United States, ranking it as Russia’s greatest foe. 40 percent of Russians viewed China as their “greatest friend,” second only to Belarus.

The year before he died in 2017, one of America’s leading twentieth-century strategic thinkers, Zbigniew Brzezinski, tried to sound an alarm. In analyzing threats to American security, “the most dangerous scenario,” he warned, would be “a grand coalition of China and Russia… united not by ideology but by complementary grievances.” This coalition “would be reminiscent in scale and scope of the challenge once posed by the Sino-Soviet bloc, though this time China would likely be the leader and Russia the follower.” Brzezinski’s specter of an “alliance of the aggrieved” is now materializing on the geopolitical map. We should remember how the last contest in trilateral diplomacy ended.

Graham T. Allison

Graham T. Allison is the Douglas Dillon Professor of Government at the Harvard Kennedy School. He is the former director of Harvard’s Belfer Center.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. Photo by Kremlin.ru shared under a Creative Commons license.