5 Years Since Russia’s Intervention in Ukraine: Has Putin’s Gamble Paid Off?

In February 2014 Russia’s “little green men” began a not-so-covert military intervention in Ukraine, stoking a conflict that has killed 13,000. In the West, Moscow’s actions were roundly condemned; for the Kremlin, they surely look different. Five years later it is worth asking: Has President Vladimir Putin’s gamble in Ukraine paid off and, if so, for whom? The answer is of paramount importance as it can illuminate Russian leaders’ decisions on future interventions—whether to pursue them, where and how.

To answer the question, this article will attempt to take stock of some key costs and benefits generated by Russia’s intervention in Ukraine at the following levels: (I) for the Russian state, measured by the impact on vital national interests as seen by Russia’s leadership; (II) for Putin personally; (III) for Russia’s ruling elite; (IV) for the Russian economy; and (V) for the Russian public.

On balance, it is this author’s view that the intervention advanced one vital national interest for Russia, as seen from the Kremlin—preventing the growing proximity of a hostile military alliance—while doing damage to several others, primarily involving development of the economy and constructive relations with both post-Soviet neighbors and key Western countries. If Putin’s hope was that the costs imposed by the West on Russia for its intervention in Ukraine would be as fleeting as the costs imposed after Russia’s intervention in Georgia in 2008, then he clearly erred in his calculations. These costs have been manageable so far, but there is a chance they can eventually become prohibitive—not only due to the cumulative impact of ever-expanding Western sanctions in the longer term, but because of Russia’s lackluster economic growth model.

I. Intervention advanced the Russian state’s interest, seen as vital by the country’s leadership, in keeping NATO at arm’s length, but also worked against the national interest in fostering trade and other ties with the West.

As I argued in my recent analysis of the drivers behind Russia’s interventions during Putin’s rule, the Kremlin’s use of force in Ukraine was meant to defend what Russia’s ruling elite see as their country’s vital interest in preventing the expansion of hostile alliances on its borders. The intervention undoubtedly delayed whatever plans the U.S. and some of its NATO allies may have had to keep a promise made to Ukraine and Georgia in April 2008, in the final communique of NATO’s summit in Bucharest, that both “will become members of NATO.”1 There is, of course, no guarantee that the alliance will not eventually grant Kiev (and Tbilisi) membership sometime in the future, but, on the current trajectory, the likelihood of such a development in the next decade is rather low, in my view. It is also my view that this kind of time horizon is sufficient for Vladimir Putin’s strategic planning purposes.

While defending Russia’s interest in keeping NATO at arm’s length, however, the ongoing intervention in Ukraine has had a negative impact on several of Russia’s other vital interests (see Table 1). For one thing, at least in the near to medium future, Moscow’s actions have made any hopes of anchoring Ukraine to Russia futile; this runs counter to Russia’s interest in being surrounded by friendly states among which it can play leading role and in cooperation with which it can thrive. Putin may be harboring hopes that a regime change in Kiev—whether through presidential elections March 31 or some other means—will bring to power someone friendlier to Moscow than Petro Poroshenko. But with or without Poroshenko it is difficult to imagine that ordinary Ukrainians will warm up to the idea of pursuing integration with Russia, at least as long as the conflict in eastern Ukraine continues. None of the top three contenders in Ukraine’s current presidential race is running on mending ties with Russia. And, as of February 2019, only 23 percent of Ukrainians wanted their country to enter the Russian-led Customs Union, while 51 percent wanted it in the EU, even without the separatist regions in Donbass, according to Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, or KIIS. (Most polls conducted since Spring 2014 have not included respondents in Donbass and Crimea.) Moreover, the share of Ukrainians who support NATO membership for their country went from 13 percent in 2012 to 41.6 percent in 2018, according to the Ilko Kucheriv Democratic Initiative Foundation.2

Table 1

|

Russia’s vital national interests affected by the intervention in Ukraine |

Impact |

|

Ensure Russian allies' survival and their active cooperation with Russia; ensure Russia is surrounded by friendly states among which Russia can play leading role and in cooperation with which it can thrive; |

Formidable lasting negative impact on efforts to anchor Ukraine. |

|

Prevent emergence and/or expansion of individual hostile powers and/or hostile alliances on or near Russian borders; |

Significant positive impact. |

|

Establish and maintain productive relations, consistent with Russian national interests, with the U.S., China and core EU members; |

Significant lasting negative impact on relations with the U.S. and EU; somewhat positive impact on relations with China. |

|

Ensure the viability and stability of major markets for major flows of Russian exports and imports; |

Significant lasting negative impact due to Western sanctions. |

|

Ensure steady development and diversification of the Russian economy and its integration into the global economy. |

Significant lasting negative impact due to Western sanctions. |

In addition to making many Ukrainians averse to Russian-led integration projects, the intervention also undermined Russia’s interest in maintaining constructive relations with the U.S. and key EU members. These relationships are now often described as Cold War 2.0 and it remains unclear whether or when they might become normal without a change of behavior by Russia in eastern Ukraine. In the meantime, NATO members are busy beefing up the alliance’s eastern flank, which obviously creates headaches for Russia’s military strategists, while also imposing rounds of sanctions on Russia over Ukraine. These sanctions, whose costs will be discussed below, cannot but damage another vital national interest of Russia’s: ensuring the viability and stability of major markets for Russian imports and exports. Since the intervention, Western countries have significantly curtailed Russia’s ability to legally import some of the technologies critical for the development of its defense electronics, shale fracking and other segments of the economy. Russia’s overall trade with the U.S. and EU countries has suffered too, though this decline probably had more to do with the petering out of Russian economic growth rather than with sanctions per se. (See Table 2 for Russia’s trade with select countries and groups of countries, as estimated by its customs service. Also, see Table 3 in Appendix for a more detailed ranking.)

Table 2

|

Countries |

Volume of trade in billions of USD, 2013 |

Volume of trade in billions of USD, 2018 |

Change in volume of trade in 2013-2018 |

|

China |

88.8 |

108.28 |

22% |

|

Netherlands |

75.96 |

47.16 |

-38% |

|

Germany |

74.94 |

59.61 |

-20% |

|

Italy |

53.87 |

26.99 |

-50% |

|

Belarus |

34.19 |

34 |

-1% |

|

Japan |

33.23 |

21.27 |

-36% |

|

Turkey |

32.75 |

25.56 |

-22% |

|

Poland |

27.91 |

21.68 |

-22% |

|

United States |

27.64 |

25.02 |

-9% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Groups of Countries |

Volume of trade in billions of USD, 2013 |

Volume of trade in billions of USD, 2018 |

Change in volume of trade in 2013-2018 |

|

EU |

417.66 |

294.17 |

-30% |

|

APEC |

208.47 |

213.26 |

2% |

|

CIS |

112.51 |

80.82 |

-28% |

II. Vladimir Putin remains in control, but he needs to eventually stop a further decline in popular trust.

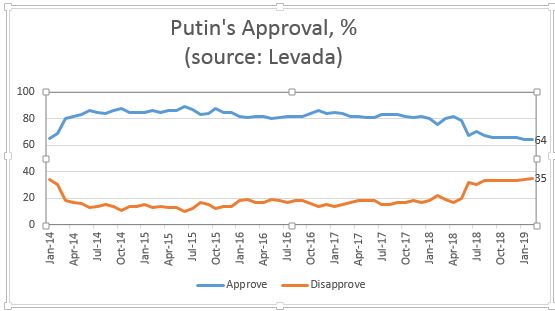

It is quite difficult to separate the impact of the intervention from other factors in explaining changes in Putin’s popularity and public trust. Yes, it is highly likely that the Russian leader’s ratings got a boost in what became known as “the Crimea effect” after Russia annexed the peninsula: As demonstrated in Chart 1, which reflects findings by Russia’s leading private pollster, the Levada Center, Putin’s popularity shot up after he became the first Russian leader since Joseph Stalin to expand the country’s territory—making Crimea’s 27,000 square kilometers and 2.25 million people part of the Russian Federation. (Though, as with the aforementioned decline in Russia’s foreign trade with certain countries, one should always be careful to separate correlation from causation and to avoid the “post hoc, ergo propter hoc” fallacy.)

Chart 1

In contrast, it is more difficult to gauge, first, what impact the subsequent Western sanctions had on the economy and, second, how that impact may have factored into the subsequent decline in Putin’s approval rating. After all, as detailed below, the Russian economy would have most probably shrunk somewhat even without sanctions due, in part, to the drop in oil prices, which remain a key driver of Russia’s economic output. We should also factor in the impact of unpopular measures recently enacted by Putin, such as approving hikes in the pension age and value-added tax, as well as hoarding money in the country’s rainy-day fund even as Russians’ real incomes continued to decline. What is clear is that Putin cannot ignore the fact that Russians’ confidence in him reached a record low this year, falling under 33 percent, according to the state-owned Russian Public Opinion Research Center, or VCIOM (see Chart 2, and compare Putin’s numbers with the 40 percent of Turks who trust in their own authoritarian ruler, Recep Erdoğan). The consensus among Kremlinologists inside and outside Russia is that Putin will probably remain in charge until the end of his fourth term in 2024. However, for Putin to either rule beyond then or install a successor, per the ruling elite’s interest in regime survival, he needs, at the very least, to prevent a further decline of popular trust in him.

Chart 2

III. ‘Sanctions? What sanctions?’ The fortunes of Russia’s ruling elite have hardly declined, if at all.

It goes without saying that much of Russia’s ruling elite—who have for years chosen to school their children, buy real estate and park money in Western countries—were not exactly happy with the way Russia’s relations with the U.S. and EU deteriorated in the wake of the Ukraine crisis. Many of them suffered from the broad restrictive measures the West imposed on Russia, while some also had the “honor” of being subjected to personal sanctions. That was the case, for instance, with Gennady Timchenko and the Rotenberg brothers, who had been close friends of Putin’s for decades and then became billionaires after he became president, in part because of the lucrative state contracts and other perks they enjoyed.

However, if we look to see whether these people’s fortunes have shrunk since the first sanctions were imposed in late March 2014, we find little change overall. The collective fortune of Russia’s richest 200 people, as estimated by Forbes magazine, went from $488 billion in 2013 to $483 billion in 2018, declining by a mere 1 percent—hardly a dramatic loss, even if Western sanctions were entirely to blame, without factoring in traditional determinants of Russia’s economic performance such as world energy prices.

Moreover, if we look at some of the men Putin “groomed” as billionaires, rather than those he “inherited” from his predecessor, they actually saw their fortunes increase despite being subjected to individual sanctions. That was the case with Timchenko, whose fortune grew by 13 percent from $14.1 billion in 2013 to $16 billion in 2018, according to Forbes; the combined fortunes of the Rotenberg brothers and their children grew too, by 12 percent from $4.7 billion in 2013 to $5.3 billion. Given these hefty increases, it should be no wonder these men are not complaining about such consequences of sanctions as the inability to continue owning personal jets.

If we were to look at an even broader tier of Russia’s rich, they collectively did well as well. The number of millionaires in Russia and their total wealth grew by 20 percent from 2015 to 2016, according to Grigory Yavlinsky’s latest book, “The Putin System,” meant to issue a damning verdict on the president’s rule. More recently, the number of Russian nationals with $30 million or more to their names grew by 7 percent in 2018 compared to 2017, according to Knight Frank’s latest Wealth Report. Of course, many of those people could have been even richer had there been no intervention and, therefore, no sanctions. However, they also know that complaining publicly about the loss of potential profits because of the country’s foreign policy is not such a good idea in a country where even complaints about domestic policies may cost you billions, and years in jail, as was the case with Mikhail Khodorkovsky. One should also bear in mind that, according to an IMF estimate, the Russian state accounts for more than one-third of Russia’s GDP3 and most, if not all, CEOs of Russia’s leading state companies are Putin’s personal friends and/or staunch loyalists, such as Rosneft’s Igor Sechin, Gazprom’s Alexei Miller and Rotec’s Sergei Chemezov who remain unwavering in their support for Putin, intervention and sanctions or not.

IV. Sanctions imposed in the wake of the Ukraine intervention did tangible damage to the Russian economy and that damage may increase with time, but the economy is far from imploding.

Ukraine-related sanctions have done considerable damage to the Russian economy, although measuring that damage with any precision is difficult for several reasons. First, as stated above, it is hard to separate the sanctions’ impact from that of other factors, such as fluctuating world energy prices.4 Second, it may be even more difficult to separate the impact of Ukraine-related sanctions from the impact of other punitive measures against Russia—over its intervention in Syria, alleged meddling in the U.S. elections and other conduct. However, these difficulties have not stopped a number of prominent experts on the Russian economy from offering their educated guesses about how much Western sanctions may have cost Russia. Former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin estimated in 2017 and 2018 that the Russian economy would have annually grown by about half a percentage point more in recent years in the absence of sanctions. It follows from Kudrin’s estimate that Russia’s 2017 GDP would have been 460 billion rubles larger (or $7.9 billion at the average rate for the end of 2017) than its 92 trillion-ruble total that year. Others estimated the damage to be higher. For instance, Bloomberg experts calculated in 2018 that the Russian economy was 10 percent smaller than it would have been without sanctions. An earlier estimate by Russian economists said Russia was losing about 1.5 percent of economic output every year.

While it is difficult to nail down exactly how much the West’s Ukraine-related sanctions have cost the Russian economy, Moscow’s Ministry of Economic Development has produced some estimates broken down by country or group of countries. A presentation posted on its website in February 2019 claims that, as of the end of 2018, all sorts of “restrictive measures” by other countries—including not just sanctions but various tariffs, quotas, special licensing and others—have cost Russia $6.3 billion.5 (Over how many years is unclear.) The most damage has been caused by the EU, which displaced Russia as Ukraine’s largest trading partner after the 2014 revolution: Its various measures have cost Russia $2.4 billion. The second-most damage, according to the ministry, has been caused by the U.S. at nearly $1.2 billion; of this, some $760 million were losses in potential sales of Russian guns and ammunition on the U.S. domestic market. (While Russia ranked first among the world’s largest arms exporters in 2013, with $7.9 billion worth of arms transferred that year, it fell to second place in 2018, with $6.4 billion worth of arms exported, or a 19-percent decline.) The Economic Development Ministry identified Ukraine as the country to do the third-most damage to Russia through its restrictions and sanctions—$775 million. In addition to these measures, Ukraine is also suing Russia for more than $160 million in damages over losses incurred by Ukrainian companies after the annexation of Crimea.

It is easier to estimate how much annexing Crimea has cost Russia’s federal budget in terms of subsidies.6 According to renowned Russian economist Sergei Aleksashenko, federal subsidies to Crimea will total 700 billion rubles ($10.6 billion) for 2014-2019. That would average out to about 116 billion rubles a year, which is significant given that the overall volume of subsidies in 2018 was reportedly a record-setting 1 trillion rubles, but could not bankrupt the federal budget, which ran a surplus of nearly 2.8 trillion rubles that year. (In addition to subsidies, state-owned companies invested another 600 billion rubles, or about $9.1 billion, into Crimea in 2014-2019, according to Aleksashenko.)

It should also be noted, of course, that some of the counter-sanctions introduced by Russia in response to the West’s punitive measures did foster growth in certain sectors of the Russian economy. For instance, Russia’s ban on many Western food products encouraged local agricultural production, which grew even as the economy tanked; overall, however, agriculture’s share in GDP was too tiny (2.4-5 percent) to make a tangible impact on economic growth. In fact, the growth of Russia’s agricultural sector has contributed around 0.1 percentage points to overall GDP growth, according to Nordea Bank analyst Tatyana Yevdokimova. The Russian economy grew by 0.7 percent in 2014, declined by 2.8 percent in 2015, declined by 0.2 percent in 2016, grew by 1.5 percent in 2017 and grew by 1.6 percent in 2018, according to the World Bank. Moreover, the bank projects that the Russian economy will grow by 1.5 percent in 2019 and another 1.8 percent in 2020, while Moody's Investor Service has raised Russia's rating to investment grade.

If anything, this growth pattern shows that, while the economic costs of the intervention have been tangible, they have not caused an economic meltdown in Russia. This could change, however, if the U.S. Congress imposes more restrictive measures and, more broadly, if the impact of even some existing sanctions is so long-term that it has yet to be fully felt, as predicted by Igor Dmitriev, the Harvard Business School-educated chief executive of Russia's sovereign investment fund.

V. Ordinary Russians are the real losers, but many of them continue to support interventions in the post-Soviet neighborhood.

While Russia has largely denied having an unsanctioned military presence in Ukraine, one estimate from a reputable source has placed the number of Russian nationals killed in the fighting higher than one-tenth of total fatalities in the five-year war. The U.N. estimated in February 2019 that the conflict in eastern Ukraine had killed 13,000 people and wounded another 30,000; of those killed 3,300 were civilians, 4,000 were Ukrainian soldiers and 5,500 separatist fighters. How many of the latter were Russian nationals is difficult to estimate. An established Russian NGO called Soldiers’ Mothers has estimated that some 1,500 Russian nationals died in eastern Ukraine in 2014-2017. A more recent estimate by the former prime minister of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic, Alexander Borodai, is that several citizens of Russia get killed in action every week in Donbass. Rather than put an end to Russia’s involvement in the conflict, which has cost so many lives on all sides, the Russian authorities have been busy trying to suppress news of casualties among Russian nationals in Donbass and, so far, public discontent with it is relatively muted—nowhere close to what it was during the first Chechen war in 1992-1994, when public outrage helped nudge Moscow toward a peace deal.

Ordinary Russians have also suffered economically, though how much of that suffering can be attributed to the Ukraine conflict and consequent sanctions is difficult to tell; either way, it does not seem to have undercut broad support for Moscow’s foreign interventions. While Russia’s economy and its richest citizens have weathered the sanctions-induced storms so far, the average standard of living has declined. Russians’ real incomes fell by 0.7 percent in 2014, 3.2 percent in 2015, 5.8 percent in 2016, 1.2 percent in 2016 and 0.8 percent in January-November 2018, according to Svetlana Misikhina, a senior scholar at the Moscow-based Higher School of Economics. At the same time, while state-sponsored polls should obviously be treated with pinch of salt, some of them do show that ordinary Russians do not feel particularly affected by the Western sanctions imposed on their country over its interventions and alleged meddling. A poll by Russia’s respected private pollster, the Levada Center, last year showed that 78 percent of Russians felt they and their families had not encountered major problems because of Western sanctions, and 68 percent of Russians were “completely unworried” or “not too worried” about the West’s “political and economic sanctions” against their country. One should also bear in mind that public servants and employees of state-owned companies have reportedly come to account for more than half of Russia’s middle class, and these people are less likely to publicly challenge the state and its policies, in part because they are dependent on the state for their livelihood. More importantly, whatever they think about their incomes, the majority of Russians have continued to support interventions. As many as 55 percent of those surveyed by Pew in August 2018 said they would support their country’s intervention in a neighboring country if “there were threats to ethnic Russians.” That does not mean, however, that Putin can continue to ignore declining incomes (and declining trust in him) indefinitely. If these downward trends continue, ordinary Russians’ strategic patience will inevitably run out.

Conclusion

When asked in 1972 about the impact of the French Revolution, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai famously (albeit mistakenly) responded: “Too soon to tell.” At this stage, it may also be too soon to tell whether Russia’s intervention in Ukraine has resulted in a net loss or gain for the successor to the late USSR. On one hand, in terms of national interests, the ongoing intervention has advanced what the Kremlin sees as Russia’s vital interest in preventing the emergence or expansion of hostile alliances on Russian borders by sending a strong signal to Kiev, Brussels and Washington that admitting Ukraine into NATO remains one of “the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin),” as then Ambassador William Burns wrote to his boss, Condoleezza Rice, shortly before Russia’s intervention in Georgia. On the other hand, that may have been the only significant geopolitical benefit that Russia derived from its use of force in Ukraine. The intervention did considerable damage to other key Russian interests: ensuring Russia can thrive, surrounded by friendly neighbors; maintaining productive relations with the United States and core European Union members; and ensuring the viability and stability of major markets for Russian exports and imports. It is debatable whether advancing these interests should have taken priority over preventing NATO expansion when Putin and his narrow circle debated in February 2014 whether to intervene in Ukraine. But it is clear that the surge in Putin’s popularity in the wake of annexation is over, and the recent decline in Russians’ confidence in their leader should worry both Putin and his key allies in the ruling elite, even if some of them have seen their fortunes increase since the intervention began. Moreover, the costs for Russia of continued alienation from the West—due to this intervention and other points of discontent—are growing and may eventually become unaffordable unless one or both of two things happen: either Russia finds a new economic model that will let its economy become competitive and grow at least as fast as the world’s as a whole—all while semi-isolated from the West—or Moscow reaches a compromise on issues of major disagreement, including the Ukraine conflict.

When Russia launched its intervention in Ukraine, some inside and outside the country wagered that the costs imposed by the West would be as fleeting as after Russia's intervention in Georgia. If Putin made such a calculation too when sending in troops, he’s lost that bet.

Footnotes

- The promise was made even though then U.S. ambassador to Moscow William Burns warned in a February 2008 email to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice that a MAP for Ukraine was “the brightest of all redlines for the Russian elite (not just Putin)” and that granting this plan to Kiev will “create fertile soil for Russian meddling in Crimea and eastern Ukraine.” The newly declassified email was included in the appendix of Burns’ recent book, “Back Channel: A Memoir of American Diplomacy and the Case for Its Renewal.”

- Other pollsters have shown different levels of support for NATO entry, but most didn’t ask respondents about this prior to the intervention, so the Ilko Kucheriv Foundation is one of the few with comparative data for before and after.

- Alternative estimates put the state’s share in Russia’s GDP as high as 75 percent. For instance, the head of Russia’s Anti-Monopoly Service, Igor Artemyev, has reportedly estimated that together with state-owned companies the Russian state’s share in GDP rose from 35 percent in 2005 to 70 percent in 2015.

- There is also a consensus among economists that Russia’s economic model, in which rising energy prices and consumption had powered economic growth in the late 1990s and early 2000s, stopped working some time ago and even a sharp increase in oil/gas prices would not bring back the annual growth of 7 percent or more that Russia saw in those years.

- See PowerPoint presentation attached at bottom of this press release.

- Crimea has received large cash injections from Moscow since 2014, when Russia annexed the Black Sea region from Ukraine. In total, an estimated 878 billion rubles ($13.3 billion) is expected to go toward improving Crimea’s roads and railways, as well as to prop up its tourism sector, between 2015 and 2022. The Russian government will invest 309.5 billion rubles ($4.7 billion) in the last three years of the Crimean development program (2019-2022), according to an update published on the Cabinet’s website.

Appendix

Table 3

|

|

|

2013 |

2013 |

|

|

2018 |

2018 |

|

|

Russia’s Top 10 trading partners in 2013 |

Billions, USD |

% in overall volume of trade |

|

Russia’s Top 10 trading partners in 2018 |

Billions, USD |

% in overall volume of trade |

|

1 |

China |

88.80 |

10.5 |

1 |

China |

108.28 |

15.7 |

|

2 |

Netherlands |

75.96 |

9 |

2 |

Germany |

59.61 |

8.7 |

|

3 |

Germany |

74.94 |

8.9 |

3 |

Netherlands |

47.16 |

6.9 |

|

4 |

Italy |

53.87 |

6.4 |

4 |

Belarus |

34.00 |

4.9 |

|

5 |

Ukraine |

39.60 |

4.7 |

5 |

Italy |

26.99 |

3.9 |

|

6 |

Belarus |

34.19 |

4.1 |

6 |

Turkey |

25.56 |

3.7 |

|

7 |

Japan |

33.23 |

3.9 |

7 |

United States |

25.02 |

3.6 |

|

8 |

Turkey |

32.75 |

3.9 |

8 |

Korea, Republic |

24.84 |

3.6 |

|

9 |

Poland |

27.91 |

3.3 |

9 |

Poland |

21.68 |

3.2 |

|

10 |

United States |

27.64 |

3.3 |

10 |

Japan |

21.27 |

3.1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2013 |

2013 |

|

|

2018 |

2018 |

|

|

Groups of countries as top trading partners, 2013 |

Billion, USD |

% in overall volume of trade |

|

Groups of countries as top trading partners, 2018 |

Billion, USD |

% in overall volume of trade |

|

1 |

EU |

417.659 |

49.6 |

1 |

EU |

294.17 |

42.7 |

|

2 |

APEC |

208.4663 |

24.8 |

2 |

APEC |

213.26 |

31 |

|

3 |

CIS |

112.509 |

13.4 |

3 |

CIS |

80.82 |

11.7 |

|

4 |

EURASEC |

60.6083 |

7.2 |

4 |

EAEU |

56.07 |

8.1 |

Simon Saradzhyan

Simon Saradzhyan is the founding director of the Russia Matters Project at Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs.

Photo by Anton Holoborodko shared under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.