Russia Analytical Report, Nov. 7-14, 2016

With the U.S. presidential election behind us, this week’s edition of Russia Analytical Report opens with a special section on the election results, their implications for U.S.-Russian relations and reactions to Donald Trump's victory in Russia. You can read our own analysis of the impact on bilateral ties here: "Trump’s Victory Bodes Well for US-Russia Ties, But Expect No Tectonic Shifts."

I. U.S. and Russian priorities for the bilateral agenda

Implications of Donald Trump’s victory in the U.S. presidential election for U.S.-Russian relations:

“Russia Isn’t Actually That Happy About Trump’s Victory,” Ruslan Pukhov, New York Times, 11.11.16: The author, a veteran defense analyst based in Moscow, argues that despite Donald Trump’s reputation as pro-Russian, “there is a lot of concern in Russia about what will happen to American foreign policy once [he] is inaugurated. The main problem with Mr. Trump is that no one—including the president-elect himself—seems to know what he will do as president, especially in the area of foreign policy. His statements on foreign relations so far have been confusing and, at times, contradictory. His aides and advisers also appear to have a broad range of conflicting views on America’s foreign and defense policy.” In the longer term, “Moscow can take comfort from some trends in American politics,” including “a renewed American proclivity toward isolationism” and the fact that globalization has not been as much of “an unalloyed boon for the United States as some wish to portray it.” In the near term, however, Russia “has very little reason to hope that the new president will offer any major concessions or strike any major deals with Moscow, regardless of what he said during the campaign.”

“Putin and the art of a deal with Russia. It is even possible that Kissinger, now 93, could play a role as adviser or intermediary,” Gideon Rachman, Financial Times, 11.14.16: The author, a regular columnist at the newspaper, offers his “best guess” on a possible deal between “Mr. Trump’s America” and “Mr. Putin’s Russia.” He speculates that Washington “will end its opposition to Russia’s annexation of Crimea,” accepting it “as a fait accompli.” Then “the U.S. will lift economic sanctions” and will “drop any suggestion that Ukraine or Georgia will join NATO. The build-up of NATO troops in the Baltic states will also be slowed or stopped.” Russia “in return … will be expected to wind down its aggression in eastern Ukraine” and stop pressuring and threatening the Baltic states. The author likewise believes Washington and Moscow “will make common cause in the Middle East,” agreeing to focus on fighting ISIS instead of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. He cautions against the “potential pitfalls” of such deal-making and says much will “depend on how Mr. Trump and his advisers assess Russian motives.” He concludes that this sort of rapprochement “would essentially represent a return to a Nixonian approach to Moscow, with the White House attempting a new form of detente with the Kremlin,” and “it is even possible that 93-year-old Henry Kissinger, who served as President Richard Nixon’s secretary of state, could play a role as an adviser or intermediary.” The author concludes, however, that “detente with the aggressive and risk-taking Mr. Putin” would be “a different and much riskier proposition [than] … with an increasingly sclerotic Soviet Union led by the relatively cautious Leonid Brezhnev.”

“What President Trump's foreign policy will look like,” David Ignatius, The Washington Post, 11.09.16: The author, a columnist for the newspaper, writes that “a Trump foreign policy, based on his statements, will bring an intense ‘realist’ focus on U.S. national interests and a rejection of costly U.S. engagements abroad.” Some likely changes would include a move to improve relations with Russia and “a joint military effort with Russia and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to defeat the Islamic State,” plus “a new push for European allies to pay more for their own defense.” The author concludes that “by putting America's interests first so nakedly, [Trump] may push many U.S. allies in Europe and Asia to make their own deals with a newly assertive Russia and a rising China. Undoing globalization isn't possible. But undermining America's leadership in that system would be all too easy.”

“Trump’s Victory Bodes Well for US-Russia Ties, But Expect No Tectonic Shifts,” Simon Saradzhyan and William Tobey, Russia Matters, 11.10.16: The authors, both affiliated with Harvard’s Belfer Center, list the “many reasons why news of Trump’s victory may have sent champagne corks popping behind the Kremlin walls and inside the Russian parliament,” but argue that ultimately the president-elect’s overtures to Moscow can translate into “some genuine improvements in the bilateral relationship” without leading to “a lasting qualitative change.” The primary obstacles to a long-term transformation include: the lack of a solid economic foundation in the relationship (statistics included); “the U.S. desire to prevent Russia from expanding its footprint in the Middle East”; “Russia’s demands for binding guarantees on the non-expansion of NATO and for constraints on U.S. ballistic missile defense systems … both of which run counter to U.S. interests”; Russia’s desire to be seen as an equal partner in “a 21st century version of the Concert of Europe, but on a global scale,” calling shots on par with America, China and the EU; fundamental disagreements on arms control; a still strong desire in Washington “to continue holding Russia accountable” for the annexation of Crimea and Moscow’s involvement in eastern Ukraine. The authors conclude that some of these issues spelled the end of the abortive 2009 “reset” with Moscow and they, along with the new hurdles that have arisen since, “will go on making any long-term qualitative improvements in the bilateral relationship unlikely.”

“Here's how Trump's election will affect U.S.-Russian relations: Experts weigh in,” Joshua Tucker, Washington Post, 11.10.16: The author, a politics professor at NYU, gives a round-up of opinions from Russian politics experts on what Donald Trump’s victory means for U.S.-Russian relations. Yoshiko Herrera and Andrew Kydd of the University of Wisconsin-Madison say Trump may do better at a “reset” than his predecessor because of his “apparent interest in reducing traditional American commitments abroad, particularly to … NATO allies”; at the same time, “given Trump's mercurial temperament and unpredictability, he could easily decide to reverse a policy of conciliation and stand firm at some point.” Dmitry Gorenburg and Michael Kofman of the nonprofit research group CNA say “Trump is at his core a dealmaker … [and] dealmakers don't generally agree to trade something for nothing. So what happens next depends in large part on what Russia will offer in return.” They predict “he is likely to restore the full range of government contacts, including between the two countries' military establishments,” to “pursue more extensive cooperation with Russia in Syria” and to end “the active sanctions policy against Russia … though existing sanctions will not be lifted without a quid pro quo.” Another possible area for cooperation involves “Russia making itself attractive as a potential partner in dealing with China.” Andrew Barnes of Kent State University expects “that Russia will continue to press against existing international institutions and norms and that Trump will generally welcome those actions, as he thinks they benefit American interests. Potential conflict will only arise when it comes to creating new rules to replace the old ones.” Several analysts, including Mariya Omelicheva of the University of Kansas, noted that “Trump is unlikely to be vocal in his criticisms of Russia's state of civil and political rights and growing authoritarianism.” She also pointed out that “the Trump government is likely to scale back … support for Ukraine, Georgia and other post-Soviet republics, giving Russia greater freedom to pursue its national interests in these states.” Eric McGlinchey and Marlene Laruelle, of George Mason University and George Washington University, respectively, argue in contrast that, due to U.S. domestic political constraints, “devoting attention to Putin does not advance Trump's position with his base. As Trump and America turn inward, the best Russia—and the world—can hope for is to not be forgotten.”

“Putin and the Kremlin are experts at reading the popular mood. And they were watching America,” Fiona Hill, Order from Chaos blog, Brookings Institution, 11.10.16: The writer, a senior fellow at Brookings and author of several books on post-Soviet Russia, points out that Russian President Vladimir Putin was “among the handful of people who seemed to” predict Donald Trump’s victory. “The reasons why are instructive.” Although “Putin does not have deep knowledge of the intricacies of U.S. party politics” and “cares little for the mechanics of the American electoral system,” his team took the “popular pulse” in America and judged that “the frustration and public dissatisfaction of a large segment of the American public, in the wake of a great recession and industrial dislocation, looked a lot like the frustration and public dissatisfaction in the USSR of the 1980s and Russia of the 1990s. The economic and societal ills of small American cities and rural areas, were familiar to the Kremlin. U.S. grassroots grievances resonated with Russian resentments. Donald Trump’s 2016 slogans had shades of Putin’s 2012 campaign: bashing out-of-touch elites, championing the little guy, projecting the image of the strong leader who could get the people what they wanted, making his country great again, and teaching everyone else a lesson in the process. … Putin and the Kremlin recognized Americans’ anger with the political establishment, because they are always on the alert for it at home. … Putin has to be fully in tune with people’s emotions to be ‘their’ president. He always has to play to the crowd. Slogans, catch phrases and pithy put-downs for opponents are more important to Putin than facts and issues, which are always fungible. Based on their own experience, the Kremlin judged (correctly) that in America’s essentially ‘Russian moment,’ a U.S. ‘Bolshevik’ and showman would better fit the angry mood than the alternative from the ancien régime.”

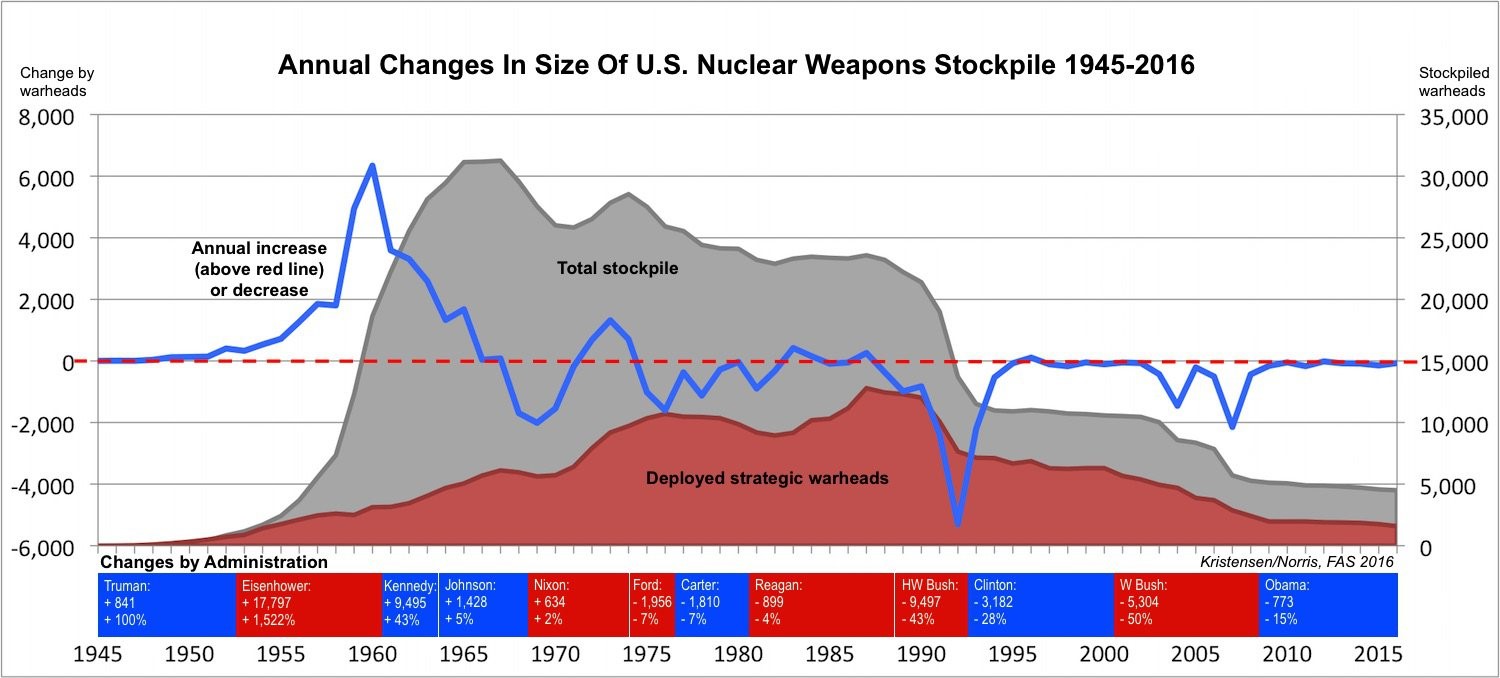

“Will Trump Be Another Republican Nuclear Weapons Disarmer?” Hans M. Kristensen, Federation of American Scientists, 11.09.16: The author, an esteemed expert on nuclear weapons and security, writes that “Republicans love nuclear weapons reductions, as long as they’re not proposed by a Democratic president. … If that trend continues, then we can expect the new Donald Trump administration to reduce the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal more than the Obama administration did.” Although “U.S.-Russian relations are different today than when the Bush administrations did their reductions,” both Russia and the U.S. “have far more nuclear weapons than they need for national security. And Trump would be strangely out of tune with long-held Republican policy and practice if he does not order a substantial reduction of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.”

Nuclear security:

- No significant commentary.

Iran and its nuclear program:

- No significant commentary.

New Cold War/sabre-rattling:

- No significant commentary.

NATO-Russia relations:

“The Plan to Deploy U.S. Troops to Norway. How Oslo and Moscow Could Respond,” Sigurd Neubauer, 11.09.16: The author, who works for a U.S. defense consultancy and is a nonresident fellow at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, examines the implications of a recent announcement that Oslo and Washington have agreed to post some 330 U.S. Marines to Vaernes Air Station in central Norway as of January 2017 to “train on their own, with Norwegian troops and with the forces of other NATO allies, making use of the area’s arctic climate to carry out cold-weather exercises.” Although the U.S. has kept defense equipment in Norway since the 1970s and agreed on a Marine “prepositioning program” more than 10 years ago, “Norwegian critics on the far left and on the populist right have decried the impending U.S. military presence at Vaernes as especially provocative” because it “could endanger Norway’s precarious but stable relationship with Russia, with which it shares a 122-mile border.” They have argued that the U.S. military presence would violate a 1949 declaration “that no allied forces can be stationed on Norway’s territory during peacetime” and could even “jeopardize the 2010 demarcation agreement between Norway and Russia.” A Russian lawmaker who is deputy chairman of a parliamentary Defense and Security Committee has said “‘Norway will suffer’ if Oslo and Washington carry out their plans at Vaernes. ‘We have never before had Norway on the list of targets for our strategic weapons,’ he said, suggesting that Norway was putting itself at risk of nuclear attack.” These “remarks suggest that further provocations could be in store if his scare tactics manage to turn more Norwegians against the U.S. troop deployment. One plausible scenario would entail a spike in Russian fighter jets encroaching on—if not outright violating—Norwegian airspace over a short period of time in order to test Oslo’s response while seeking to capitalize on populist anxiety by stoking a media controversy. Another scenario would involve a large-scale Russian military exercise near the Norwegian border. It should be noted, however, that a rotational U.S. military presence in Norway is by itself unlikely to trigger either scenario. Either course of action would be opportunity driven: Moscow would have to use the deployment as a convenient pretext to respond to some other dramatic shift in the fraught U.S.-Russian relationship.” Norway’s domestic political “dynamics, coupled with the deteriorating U.S.-Russian relationship, could set the stage for Russia to direct more bellicose rhetoric at Norway with the aim of galvanizing the anti-NATO constituencies on Norway’s left and making inroads among right-wing populists.”

Missile defense:

- No significant commentary.

Nuclear arms control:

- No significant commentary.

Counter-terrorism:

- No significant commentary.

Conflict in Syria:

- No significant commentary.

Cyber security:

- No significant commentary.

Energy exports from CIS:

- No significant commentary.

U.S.-Russian economic ties:

- No significant commentary.

U.S.-Russian relations in general:

“The Bear Is Growling: Former CIA Chief's Report From Russia,” John McLaughlin, Ozy, 11.08.16: The author, who was a deputy director and acting director of the CIA (2000-2004) and teaches at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, writes that “the new U.S. president will begin by dealing with a Russia that is hostile, aggressive and tightly controlled by President Putin. … If Putin has a weakness, it lies in the irony that he desperately needs the U.S. as an adversary to unite his supporters and to distract from worsening domestic problems” and, “if you just looked to the Russian state-controlled media, you would have to say that armed conflict is quite possible.” The incoming U.S. administration, the author argues, “will need a Russia policy with four elements: clarity, deterrence, communication and a way forward. Clarity: The administration must be clear about … what we want in the relationship and what we are prepared to recognize as Russia's legitimate interests. … Deterrence: Deterring Moscow from actions we oppose will require firmness applied with greater agility than we typically display. … Communication: Official communication with Russia is today more limited in scope and frequency than during the early years of Russian independence in the 1990s, and even during the Cold War. Change will take time and patience, and there is no guarantee that more frequent discussions will resolve many problems,” but communicating is better than the more violent alternatives. Finally, we need a “Way Forward: The U.S.-Russia relationship is burdened with such deep mutual distrust that it will not improve quickly and may get worse before any improvement is possible. Probably the best that can be done is to start with so-called confidence building measures (CBMs) — engagements that, though politically sensitive, may be more technical in nature and less complicated than, say, Syria.”

II. Russia’s relations with other countries

General developments and “far abroad” countries:

“Japan must proceed cautiously with Russia,” Financial Times, 10.07.16: This editorial considers the “curious diplomatic dance” Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe is conducting with Russian President Vladimir Putin at a time when contention over Ukraine and Syria are increasing “the distance between the Russian government and Japan’s allies in the EU and the U.S.” Putin plans to travel to Japan next month, “his first visit as president in 11 years” and “both leaders have invested in achieving a significant result,” including resolving their decades-old territorial dispute over four small islands. “Drawing closer to Russia is also part of Japan’s China strategy,” says the article, as “Abe hopes that greater influence with Russia will deter the forging of a deeper Chinese-Russian alliance.” Japan has focused on expanding economic ties, a welcome prospect in Moscow in the face of economic stagnation and “long-delayed energy development projects, particularly in Siberia.” But the editorial’s tone is skeptical: “Japan’s approach to Mr. Putin threatens to weaken G7 co-ordination, and undermine sanctions against Moscow.” And “many experts believe Japan can only hope to get two tiny islands back… [which] make up 7% of the islands’ land mass, and have little economic or security value. For this small gain, Japan cannot risk alienating the U.S. or the EU. Nor should Japan expect Russia to provide much meaningful support in its rivalry with China, even after a peace treaty is signed. Russia is deeply wary of China, but its hope for stronger economic ties, particularly in the form of pipelines to send natural gas eastward, is stronger still.”

China:

- No significant commentary.

Ukraine:

- No significant commentary.

Russia's other post-Soviet neighbors:

- No significant commentary.

III. Russia’s domestic policies

Domestic politics, economy and energy:

“Vladimir Putin is reshaping the Kremlin’s political elite,” Andrei Vinokurov, Alexander Atasuntsev, Gazeta.ru/RBTH, 11, 10.16: Russian President Vladimir Putin is “forging a new inner circle of advisors and supporters in order to consolidate the political system he has created,” according to a new report by Minchenko Consulting. The regularly updated Politburo 2.0 Report is based on the idea that, by 2012, “Putin had formed a separate informal governing instrument that in many ways resembles the Soviet Politburo.” Its members “are essentially the senior managers of the Russian government,” each responsible for his or her own patch, while Putin acts “as an arbiter, resolving all disputes and occasionally redistributing influence” within the group. The report reviews some of the recent “regrouping of forces in the highest and middle echelons of the Russian nomenklatura,” including “the dismissal of high-profile representatives of Putin’s ‘old guard’” (like former presidential administration head Sergei Ivanov and former railways chief Vladimir Yakunin), “the activation of an anti-corruption agenda and its use in the inner elite struggle,” changes in law enforcement and new lawmakers in parliament’s lower house. The report cites one reason for the change as “‘Putin's unwillingness to become a hostage to his entourage’” and his attempts to form a more autonomous, competitive “election coalition” and “future power configuration.” This has required a weakening of most members of the Politburo 2.0, although “Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu has become stronger during wartime and equal to the director of Russia's renewed National Guard Viktor Zolotov.” The report’s authors believe “the president is testing young technocrats” (like Ivanov’s replacement, Anton Vaino, and Industry and Trade Minister Dmitri Manturov), “‘princes’ from elite families who position themselves as technocrats (Moscow Region Governor Andrei Vorobyov), people close to him (Tula Region Governor Alexei Dyumin, who for a long time worked in the presidential guard), as well as social and party activists.” The report predicts that the Politburo shake-up will favor people with the potential “to ‘effectively conduct communication with Europe and the U.S.,’” including former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin and former presidential chief of staff Alexander Voloshin. Despite his reputed love for checks and balances, “‘Putin doesn’t need powerful clans,’” says political analyst Alexei Makarkin. “‘As soon as the objective is reached, the appointees go home. This is the system that currently suits him most.’”

Defense and aerospace:

- No significant commentary.

Security, law-enforcement and justice:

- No significant commentary.

Selection of commentary for this digest is curated by Simon Saradzhyan.