Russia Analytical Report, Jan. 17-23, 2023

3 Ideas to Explore

- Contrary to claims that it costs the U.S. “peanuts” to prop up Ukraine in its defense against Russia, this support comes at a price—which has already exceeded America’s annual expenses on its wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, according to Trita Parsi of the Quincy Institute. “The value of degrading Russia’s military—which clearly was overrated in the first place—may not be that significant, even if it is done on the cheap,” according to Trita. This supports also comes at a strategic cost, such as the “formation of a Russian-Chinese-Iranian alliance,” he writes in the New Republic.

- To prevent strengthening China’s alignment with Russia, America should quietly gauge Beijing’s interest in mediating a resolution of the Ukraine crisis, according to Robert Manning and Yun Sun of the Stimson Center. A possible entry point to U.S.-China dialogue on this issue is a “mutual concern about Putin’s public threats of nuclear use and the consequences of breaking the 77-year-old nuclear taboo,” they write in FP. “An interest-based transactional approach [by the U.S. toward China] could go far in avoiding the self-fulfilling prophecy of a Beijing-Moscow alliance,” they argue.

- It’s a mistake to make Germany the villain over its reluctance to provide tanks to Ukraine, according to Hal Brands of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. “For all its shortcomings, Germany’s Ukraine policy has been remarkable: Who, a year ago, would have predicted that Germany would respond to the invasion by decisively slashing its dependence on Russian energy? That it would send, however ambivalently, howitzers, air defenses and armored vehicles to Kyiv?” Brands asks in his column for Bloomberg.

I. U.S. and Russian priorities for the bilateral agenda

Nuclear security and safety:

- No significant developments.

North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs:

- No significant developments.

Iran and its nuclear program:

- No significant developments.

Humanitarian impact of the Ukraine conflict:

“How to bring Putin and his henchmen to justice,” Editorial Board, WP, 01.22.23.

- “Ukraine, key Western nations as well as the International Criminal Court have gathered reams of incriminating data that can and should be used as evidence to prosecute Russian commanders in Ukraine for particular war crimes. But it would be a travesty to haul those officers into the dock while turning a blind eye to the culprits in the Kremlin.”

- “In this case, a new, purpose-built tribunal is required, because the International Criminal Court in The Hague lacks jurisdiction to get at the war's true authors.”

- “Seen from today's vantage point, chances seem remote that Mr. Putin or his henchmen can be held meaningfully to account. Prosecutions seemed similarly remote in previous instances—during World War II, and as fighting raged in the former Yugoslavia and elsewhere before, at last, they became reality with the establishment of tribunals to do the job. Without a court empowered to try Russia's top leaders for a war of aggression, justice for them will remain a chimera. With such a tribunal, it at least becomes possible.”

Military aspects of the Ukraine conflict and their impacts:

- “For both sides, 2023 will see attempts to redraw largely static battle lines. A front line of World War I-style trenches might become a more fluid and unpredictable battlespace this year.”

- “The appointment of Gerasimov is Putin's latest Hail Mary pass, and U.S. officials doubt it will succeed. The biggest problem is the chaotic command structure under him. Hastily trained conscripts are being rushed to the front as little more than cannon fodder. Meanwhile, the Wagner militia, led by catering oligarch Yevgeniy Prigozhin, has taken a lead role in the bitter but strategically meaningless battle for Bakhmut in eastern Ukraine.”

- “Gerasimov will try to restore military order among bickering commanders and also initiate complex operations of the sort he envisioned in 2013. One expert skeptically recalls a Russian proverb: ‘He can't outleap himself.’”

- “As the new year dawns, Ukraine appears to be generating momentum. The United States and its NATO allies are providing a new arsenal of mobile weapons—tanks and heavy armored vehicles that would, in theory, allow the Ukrainians to conduct American-style maneuver warfare.”

- “This year might prove decisive in Ukraine. Having wisely urged Ukraine to adopt maneuver warfare against Gerasimov's battered, bunkered forces, the United States and its allies shouldn't support this effort halfway. The West has a strategy: So, go for it.”

- “Wagner financier Yevgeny Prigozhin’s star has begun to set after months of apparent rise following his failure to make good on promises of capturing Bakhmut with his own forces. Russian President Vladimir Putin had likely turned to Prigozhin and Prigozhin’s reported ally, Army Gen. Sergey Surovikin, to continue efforts to gain ground and break the will of Ukraine and its Western backers to continue the war after the conventional Russian military had culminated and, indeed, suffered disastrous setbacks.”

- “Putin appears to have decided to turn away from relying on Prigozhin and his irregular forces and to put his trust instead in Gerasimov, Shoigu and the conventional Russian military once more.”

- “Putin’s decision to focus and rely on conventional Russian forces is marginalizing the Wagner Group and the siloviki faction that nevertheless continues to contribute to Russian war efforts in Ukraine. … Putin is also attempting to rebuild the Russian MoD’s authority and reputation … Putin’s turnabout became most evident when he pointedly did not credit Prigozhin or his Wagner forces for the capture of Soledar during a federal TV interview on Jan. 15.”

- “Putin may have felt threatened by Prigozhin’s rise and tactless self-assertion. Putin began to reintroduce himself as an involved wartime leader in December … The return to prominence and influence of more professional military officers such as Gerasimov likely suggests a reduced likelihood that Putin will give in to the crazier demands of the far-right pro-war faction, possibly in turn further reducing the already-low likelihood of irrational Russian escalations.”

- “But the re-emergence of the professional Russian military is also concerning. … His re-embrace of Gerasimov and regular order has likely put Russia back on course toward rebuilding its military. NATO would do well to take note of this development as a matter of its own future security, beyond anything it might portend for Ukraine.”

- “The war in Ukraine has also exposed serious deficiencies in the U.S. defense industrial base. U.S. assistance to Ukraine has been critical to halting Russian revanchism and sending a message to China about the costs and risks of aggression—and needs to continue. But it has also depleted U.S. stocks of some types of weapons systems.”

- “The history of industrial mobilization suggests that it will take years for the defense industrial base to produce and deliver sufficient quantities of critical weapons systems and munitions and recapitalize stocks that have been used up.”

- “As the war in Ukraine illustrates, a war between major powers is likely to be a protracted, industrial-style conflict that needs a robust defense industry able to produce enough munitions and other weapons systems for a protracted war if deterrence fails. Effective deterrence hinges, in part, on having sufficient stockpiles of munitions and other weapons systems. These challenges are not new. What is different now, however, is that the United States is directly aiding Ukraine in an industrial-style conventional war with Russia—the largest land war in Europe since World War II—and tensions are rising between China and the United States in the Indo-Pacific. Timelines for a possible war are shrinking.”

“Heavy tanks—and a push from the U.S.—are key to Ukraine’s success,” Editorial Board, WP, 01.17.23.

- “To position Kyiv not only to blunt the coming Russian attacks but to push the enemy back to pre-invasion lines, Ukraine needs more and heavier weapons. First on the list are top-grade battle tanks—specifically, German-made Leopard 2s—in sufficient numbers to turn the war's tide. For that to happen, Germany's assent is required. And given the training and logistical hurdles Ukraine faces before it could deploy such heavy tanks, the timing is critical.”

- “So far, Germany is on the fence, its coalition government apparently split, and polls indicate the German public is also divided on the question. Chancellor Olaf Scholz is reluctant but also publicly on record as awaiting Washington's input. Delivering Leopard tanks to Ukraine, he said earlier this month, depends ‘especially [on discussions] with our transatlantic partner, with the United States of America.’”

- “That amounts to a plea for stepped-up U.S. leadership. The question is whether Mr. Biden, who has vowed not to permit a Russian victory and pledged to stick with Kyiv ‘as long as it takes,’ is prepared to demonstrate even more resolve as the war in Ukraine approaches what is likely to be its decisive moment.”

- “Moscow is gearing up for a major spring offensive, expected to start in the next two months. Ukraine might launch one of its own. What is at stake is not only Ukraine's survival, but also leadership and clear-eyed thinking in Washington and Berlin. Germany's hesitation [on supplies of Leopard-2 tanks to Ukraine] is a critical challenge to Western unity, and Mr. Biden cannot sit pat in the face of it.”

- "Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power in China have raised fears of a comparable military conflict in the Taiwan Strait. ... While the fighting in Ukraine is on land, and thus very different from the maritime battlefield that would surround Taiwan, there are still many things my island nation can learn from Ukraine's defensive operations. One similarity in particular is that Taiwan, like Ukraine, is a relatively weak power facing the threat of a much larger one—and that asymmetry lies at the heart of many of the lessons outlined below, including that a nation’s security cannot rely solely on promises of peace and that continuity of government operations is vital."

-

"1. National security cannot rely solely on promises of peace, even in writing. ... 2. Continuity of government operations both demonstrates and bolsters a people’s determination and will to resist a military onslaught."

-

"3. A military strategy based on sea denial. ... 4. Take threat signals seriously and strengthen defenses rapidly. ... 5. Redesign investment strategies to account for military asymmetry."

-

"6. Design an effective communications strategy. ... 7. Strengthen defensive resilience. ... 8. Conduct joint training with allied partners but prepare for the worst-case scenario."

Punitive measures related to Russia’s war against Ukraine and their impact globally:

- “The assertion that the Russian economy has shown remarkable resilience to sanctions hinges on misleading macroeconomic indicators.”

- “Official unemployment currently stands at 3.7 percent, with only 2.7 million Russians unemployed. That’s a record low. The reality, however, is that at the end of the third quarter of 2022, almost five million Russian workers were subject to various forms of hidden unemployment. … 70 percent of them were on unpaid leave. … 10 percent of the Russian workforce is without work. This is comparable with the worst levels in the 1990s.”

- “Another misleading statistic is the ruble exchange rate. ... The so-called strong ruble is propped up by draconian currency controls and a plunge in imports.”

- “Policymakers criticizing sanctions point to the Russian Finance Ministry’s projection that the country’s GDP will contract by 2.7 percent, which would seem to undermine the contention that the economy is tanking. Note, however, that this GDP figure includes surging military-related production.”

- “Arguably the most revealing indicator of Russian economic activity is revenue from sources other than oil and gas exports, and that figure was down by 20 percent in October 2022 from a year earlier.”

- “Even the Russian central bank currently reports that observed inflation—that is, how the public views the increase in prices, as reported in surveys—to be 16 percent, or over four percentage points higher than the official statistic, which is a little less than 12 percent.”

- “The Public Opinion Foundation … reported in December 2022 that only 23 percent of Russians considered their personal financial situation to be ‘good.’”

- “All of this is not to say that Putin’s government is on the verge of collapse. ... But public opinion is trending against Putin. As the dissolution of the Soviet Union demonstrates, once long-suppressed public discontent breaks out into the open, change can happen fast. This is why policymakers must give sanctions time to work.”

- “Thanks to an unseasonably warm winter in Europe, Putin’s moment of maximum leverage has passed uneventfully, and, as we correctly forecast last October, the biggest victim of Putin’s gas gambit was Russia itself. Putin’s natural gas leverage is now nonexistent, as the world—and, most importantly, Europe—no longer needs Russian gas.”

- “Europe is now assured sufficient energy supply well into 2024 at a minimum, providing enough time for cheaper alternative energy supplies—both renewables and bridge fuels—to be fully onboarded and operating within Europe.”

- “Putin’s oil leverage is likewise diminishing. Gone are the days when fear of Putin taking Russian oil supplies off the market caused oil prices to skyrocket by 40 percent over two weeks. In fact, when—in response to last month’s rollout of the G-7 oil price cap, which we helped develop—Putin announced a ban, from Feb. 1, on oil exports to countries that accepted the price cap, oil prices actually went down.”

- “Even Putin’s other commodities cards are all used up. His gambit to weaponize food abjectly collapsed when even his nominal allies turned on him. And in certain metals markets where Russia historically dominated, such as nickel, palladium, and titanium, blackmail-fearing buyers combined with higher prices have expedited reshoring and reinvigorated dormant public and private investment in critical mineral supply chain and mining projects.”

- “The war on the battlefield is still being fought, but on the economic front at least, victory is in sight.”

Ukraine-related negotiations:

- No significant developments.

Great Power rivalry/new Cold War/NATO-Russia relations:

- “Does the war in Ukraine enable the United States to strategically defeat Russia on the cheap? This has become a central argument for countering pressures to end the war or cut its funding [e.g. Anthony Cordesman and Timothy Ash made such an argument].”

- “The cost of the war thus far is not, contrary to Ash, “peanuts.” The U.S. support for Ukraine in 2022 amounted to $68 billion, and the White House requested another $34 billion. In comparison, the war in Afghanistan cost $23 billion per year in its first two years.

- “Arguing that continuing the war is an affordable way of achieving a major strategic objective is misleading—not least because, prior to February 2022, few in Washington considered Russia a major power whose military needed to be degraded to protect the U.S. … The value of degrading Russia’s military—which clearly was overrated in the first place—may not be that significant, even if it is done on the cheap.”

- “There are other strategic costs. As the war drags on, it contributes to the formation of a Russian-Chinese-Iranian alliance. ... Washington’s objective should be to disrupt any such alliance-building rather than to hasten it. … The war has added to … tensions between the U.S. and rising global south powers, who refuse to choose between the U.S., Russia and China … Rather than boosting efforts to decarbonize the global economy, the war has caused nations to backslide on key environmental goals.”

- “Perhaps most importantly, prolonged war will make it increasingly hard for Europe to find a path back to long-term peace and stability. … Europe may find itself in a state of constant, low-intensity war that cements enmity beyond generations. This, in turn, risks creating a new normal where peace no longer can be imagined, let alone achieved. … These costs don’t show up on the current balance sheets. But it is these costs—rather than the dollar amounts of the military aid—that we will be wrestling with in the years to come.”

- “The differences [among NATO allies with regard to the war in Ukraine] are over strategy for the coming year and the more immediate question of what Ukraine needs in the next few months, as both sides in the war prepare for major offensives in the spring. And while most of those debates take place behind closed doors, Britain’s impatience with the current pace of aid and Germany’s refusal to provide Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine broke out into public.”

- “When the new British foreign secretary, James Cleverly, visited Washington this week, he gathered reporters for lunch and made the case that it is possible for Ukraine to score a ‘victory’ in the war this year if the allies move fast to exploit Russia’s weaknesses. Officials in Poland, the Baltic States and Finland have largely agreed with the British assessment. American officials pushed back, saying it is critical to pace the aid, and not flood Ukraine with equipment its troops cannot yet operate. And they argue that in a world of limited resources, it would be wise to keep something in reserve for what the Pentagon believes will likely be a drawn-out conflict, in which Russia will try to wear Ukraine down with relentless barrages and tactics reminiscent of World War I and II.”

“Is Germany Letting Ukraine Down? It’s Not That Simple,” columnist Hal Brands, Bloomberg, 01.22.23.

- “Scholz has averred that Germany will send tanks only as part of a larger coalition involving the U.S. ... The annoyance is palpable in Kyiv, Warsaw and other Eastern European capitals that worry less about provoking Putin than about defeating him. Add in the fact that Scholz beat a path to Beijing as soon as Chinese President Xi Jinping began accepting post-Covid visitors in November, and questions abound about whether Germany—the world’s fourth-largest economy—is serious about meeting the threats to a global order that has served it so well.”

- “Still, it’s a mistake to make Germany the villain in a geopolitical morality play. For all its shortcomings, Germany’s Ukraine policy has been remarkable: Who, a year ago, would have predicted that Germany would respond to the invasion by decisively slashing its dependence on Russian energy? That it would send, however ambivalently, howitzers, air defenses and armored vehicles to Kyiv?”

- “Taking the longer view, one can criticize Germany for being naive about Putin’s Russia and becoming economically handcuffed to a nasty autocracy. Then again, the U.S.—and many of Europe’s largest democracies—are guilty of similar mistakes.”

- “Above all, it’s worth remembering that the characteristics that critics of German foreign policy find so frustrating are the same characteristics that helped transform a once-bellicose country into the peaceful, liberal state we know today.”

- “The good news is that Berlin’s foreign policy is headed, albeit fitfully and belatedly, in the right direction. The bad news is that Ukraine may not have the luxury of waiting for a zeitenwende to play out at a leisurely pace.”

China-Russia: Allied or aligned?

- “The United States should seek to explore Sino-Russian fault lines rather than mitigate and bridge their differences for them.”

- “As one of the few parties that still possess critical influence over Russia’s decision-making, China’s early offer to mediate in the Ukraine crisis should be probed. China might claim that it is not a party to the conflict, though it has been an enabler. Washington should make it clear that, as a great power, Beijing cannot evade the responsibility of bringing the war to a speedy end.”

- “A possible entry point to U.S.-China dialogue on Ukraine is mutual concern about Putin’s public threats of nuclear use and the consequences of breaking the 77-year-old nuclear taboo.”

- “In addition, Washington must look beyond the war to think through both ways and means of its termination as well as the future of Ukraine’s economic reconstruction. ... If China, the world’s leading lender, is not offered an opportunity to be included in that discussion or to coordinate efforts, a separate Chinese reconstruction effort may complicate or obstruct Western efforts. Dialogue on China doing its fair share in a coordinated and global campaign should be explored.”

- “The United States would be wise to tone down its moral rhetoric and initially use a quiet backchannel approach to Beijing to gauge interest. It should emphasize the limited and realistic scope of issues and try to shape a Ukraine agenda during Blinken’s forthcoming trip to China.”

- “An interest-based transactional approach could go far in avoiding the self-fulfilling prophecy of a Beijing-Moscow alliance.”

Missile defense:

- No significant developments.

Nuclear arms

“Russia Needs to Learn to Lose Like America,” Matthew Gault, Vice, 01.20.23.

- “Former Russian president and current deputy chairman of the Kremlin’s Security Council, Dmitry Medvedev, told the world that Russia losing its war in Ukraine might lead to a nuclear war in a Telegram post on Thursday. This is what nuclear experts call nuclear blackmail. America has tried it several times in the past and it never quite works out the way the politicians making the threat think it will.”

- “In 1950, President Harry Truman said the use of atomic weapons was on the table for the Korean War.”

- “After Truman left office, former general Dwight D. Eisenhower took over the presidency. He, too, threatened to use nuclear weapons on China. First, in 1953 as a means of bringing the country to the negotiating table over Korea. Then again in 1955 when China seized a group of islands in the Taiwan Strait.”

- “Some members of America’s military leadership wanted to use nukes to turn the tide in Vietnam during the 1960s and ‘70s. Plans were drawn up and generals pushed the president to issue public threats, but both Kennedy and Johnson demurred. Nixon did want Hanoi and Moscow to think he would drop a nuke, but all three presidents avoided using nuclear weapons to get out of a humiliating defeat in southeast Asia. Any one of these presidents could have dropped a bomb to win some kind of victory. None did.”

- “Russia needs to learn from America and know how to lose without using nuclear weapons. Better yet, it can learn that invasion and occupation should be avoided in the first place.”

- “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was a tragedy and a crime, but it does not threaten American security.”

- “There are still good reasons to punish Russia for overt aggression and assist Kyiv in preserving its independence, but these interests are limited. Americans who want to fight should feel free to do so—after booking a flight to Europe and joining the Ukrainian army. They should not be pushing the other 330-plus million Americans toward the conflict.”

- “U.S. policymakers should strictly limit assistance to Kiev. Washington should emphasize bolstering Ukraine’s defense, frustrating further Russian attacks and encouraging both sides to seek diplomatic solutions. The U.S. should not underwrite a grandiose Ukrainian campaign for victory, especially to recapture the rest of the Donbass and Crimea. Doing the latter could become the trigger for nuclear threats and even strikes by Moscow. The cause is not worth the risk for America.”

- “Three hundred nuclear missiles are screaming toward the U.S. This is likely a pre-emptive strike by Russia to destroy all land-based intercontinental ballistic missile silos in the country. Anti-missile defenses cannot knock out many of the incoming rockets, meaning 2 million Americans will die. ... This immersive experience has been devised by Sharon Weiner and Moritz Kütt, two national security experts from Princeton University, who have tested it on dozens of people to see how they respond. … It is based on the current U.S. nuclear launch protocols that have changed little since the height of the Cold War. In a controlled experiment with 79 participants, 90% chose to launch a nuclear counter-strike.”

- “Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has prompted many to question Putin’s rationality. At the beginning of last year, he swore that he did not intend to attack Ukraine. In October, he said he saw no point in a nuclear strike. But fears of nuclear war have skyrocketed since the outbreak of conflict, says Beatrice Fign, the Nobel-winner who inspired Moran Cerf, a 45-year-old Israeli neuroscientist who is campaigning to nuclear launch rules. … The Russian-language page of her International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons website, explaining the humanitarian consequences of a nuclear exchange, has been one of the most visited on the site. Only by working for the complete elimination of nuclear weapons, she says, can the world ever be safe from the threat of Armageddon.”

- “Still Fihn, like many of the experts I interviewed for this article, rejects fatalism. Most were hopeful that change is possible. … Cerf also describes himself as an optimist. When researching his film, he was surprised by how willing his interviewees were to talk. ‘In all the countries, this knowledge is burning inside them,’ he says. ‘I do imagine the U.S. making drastic changes.’”

- “Russian propaganda ... absolves Russia, blames the United States for the war and has four main tenets: first, that a long-standing American effort to bring Ukraine into NATO poses a grave threat to Russian security. Second, that American shipments of weapons to Ukraine have prolonged the fighting and caused needless suffering among civilians. Third, that American support for Ukraine is just a pretext for seeking the destruction of Russia. And, finally, that American policies could soon prove responsible for causing an all-out nuclear war.”

- “Those arguments are based on lies. They are being spread to justify Russia’s unprecedented use of nuclear blackmail to seize territory from a neighboring state. Concerns about a possible nuclear exchange have thus far deterred the United States and NATO from providing Ukraine with the tanks, aircraft, and long-range missiles that might change the course of the war. If nuclear threats or the actual use of nuclear weapons leads to the defeat of Ukraine, Russia may use them to coerce other states. Tactics once considered immoral and unthinkable might become commonplace. Nuclear weapons would no longer be regarded solely as a deterrent of last resort; the nine countries that possess them would gain even greater influence; countries that lack them would seek to obtain them; and the global risk of devastating wars would increase exponentially.”

- “A proper conclusion of the war in Ukraine will require many complex issues to be resolved … The Ukrainian government, not the United States or NATO, will have to decide how to proceed. But the basis of a just settlement is simple. When a reporter asked Sanna Marin, the prime minister of Finland, whether Russia should be given an ‘off-ramp’ to avoid its humiliation and prevent nuclear war, she didn’t fully understand the question at first. … A way out of the conflict, the reporter explained. ‘A way out of the conflict?’ Marin asked. ‘The way out of the conflict is for Russia to leave Ukraine. That’s the way out of the conflict. Thank you.’”

Counterterrorism:

- No significant developments.

Conflict in Syria:

- No significant developments.

Cyber security:

- No significant developments.

Energy exports from CIS:

“Vladimir Putin is losing the energy war,” energy editor David Sheppard, FT, 01.20.22.

- “Vladimir Putin’s energy war is suddenly going about as well as his ‘special military operation.’ That is, to say, not very.”

- “In the past month, natural gas prices have plummeted. After trading near €150 per megawatt hour ($48 per million British thermal units) at the beginning of December they have fallen below €60/MWh ($19 per mmbtu) this week. ... Prices are about twice the level we once would have considered on the high side in a normal winter, but are no longer 10 times that, as they were last summer when Russia’s fully cut off of its main gas pipeline to Europe.”

- “It would be foolish to rule out further price volatility. But Russia’s weaponized energy strategy is really on borrowed time. ... By 2024/25, more LNG will start arriving on to the global market, easing the supply situation and making extreme price spikes much less likely.”

- “Governments such as Germany’s have shown they can move quickly in a crisis, establishing floating LNG terminals in a matter of months to open up alternatives to Russian gas. The same urgency now needs to be applied to longer-term solutions, be that offshore wind, hydrogen or nuclear, while speeding up the long-term process of reducing the use of gas in heating. That will be the only way to decisively declare victory in the energy war.”

Climate change:

- No significant developments.

U.S.-Russian economic ties:

- No significant developments.

U.S.-Russian relations in general:

- “The regime of Russian President Vladimir Putin is living on borrowed time. The tide of history is turning, and everything from Ukraine’s advances on the battlefield to the West’s enduring unity and resolve in the face of Putin’s aggression points to 2023 being a decisive year. If the West holds firm, Putin’s regime will likely collapse in the near future.”

- “Yet some of Ukraine’s key partners continue to resist supplying Kyiv with the weapons it needs to deliver the knockout punch. The administration of U.S. President Joe Biden in particular seems afraid of the chaos that could accompany a decisive Kremlin defeat. It has declined to send the tanks, long-range missile systems, and drones that would allow Ukrainian forces to take the fight to their attackers, reclaim their territory and end the war.”

- “The end of Putin’s tyrannical rule will indeed radically change Russia (and the rest of the world)—but not in the way the White House thinks. Rather than destabilizing Russia and its neighbors, a Ukrainian victory would eliminate a powerful revanchist force and boost the cause of democracy worldwide.”

- “This is a make-or-break moment for Ukraine. Biden can turn the tide in Kyiv’s favor by backing up his declarations of support with the delivery of tanks and long-range weaponry. He can also hasten the demise of Putin’s regime, opening up the possibility of a democratic future for Russia and demonstrating to the world the folly of military aggression. The United States cannot let its fears stand in the way of Ukraine’s hopes.”

II. Russia’s domestic policies

Domestic politics, economy and energy:

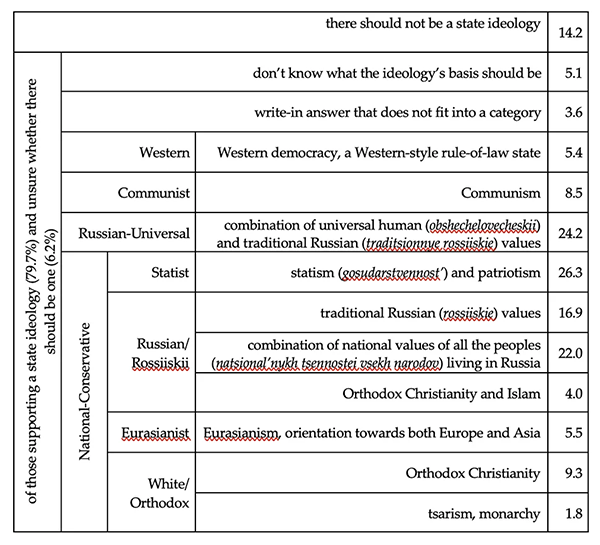

- “The Russian Constitution explicitly bans the establishment of a state ideology ... but what do Russians think about a new state ideology? For the first time, we have at our disposal a survey exploring the bottom-up demand for state ideology. In spring 2021, the LEGITRUSS telephone survey conducted by VTsIOM asked a nationally representative sample of 1,500 Russians: ‘Does Russia need a state ideology?’ … In the affirmative answered 79%, while 14% said no and 7% were not sure.”

- “The 79% of respondents who said that Russia needs a state ideology were able to select (or write in) up to two things that should form the basis … of the state ideology.”

- “Asserting the Russian public’s lack of ideology, as is commonly done by observers, should be done with caution. ... [T]here indeed seems to be a majority public opinion that is at least partly synchronized with the national-conservatism promoted by the Kremlin. One can debate whether it is ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up,’ deep-seated in citizens due to shared collective and individual experience or constructed by media narratives. But the popular support for it is there, and it should be taken into consideration if we want to understand much of Russian society’s defensive consolidation in wartime. Another important takeaway is that the Kremlin knows what it is doing in shaping its propaganda message: the Presidential Administration is fairly expert at tapping into existing perceptions and reinforcing them.”

- “The Kremlin is busy developing a new strategy to deal with the unprecedented recent wave of emigration that has seen hundreds of thousands of people decide to leave Russia. In particular, the Kremlin has been enraged by statements from famous Russian actors and comedians using the freedom of exile to speak out against the war. ... Measures subsequently proposed by parliamentarians include the confiscation of all property in Russia and the cancellation of Russian passports.”

- “The measure is not a mere expression of dictatorial frustration. It is highly effective and carefully designed. While the world has changed dramatically since the end of the Iron Curtain, exiles still need documents, and these days the red Russian passport is the only piece of paper most Russian refugees, including activists, journalists and IT entrepreneurs have at their disposal. Applying for political asylum is a difficult, time-consuming and cumbersome process.”

- “Confiscation of property and citizenship termination are not the only measures under consideration. Former Russian President Dmitry Medvedev ... advocated acting ‘according to the rules of wartime,’ citing Russia's experience in World War II … Medvedev has posted increasingly extreme diatribes attacking the West since the invasion of Ukraine started, but this is the first time a high-level Russian official has openly called for the use of assassins to deal with Kremlin critics.”

- “Yet at the same time, there is a part of the recent emigration wave that the Kremlin is very keen to entice back. Maksut Shadayev, the head of the Digital Development Ministry, a young and apolitical official in Vladimir Putin’s government ... wants to get Russian IT specialists who fled abroad to protest the invasion and avoid mobilization to return to Russia.”

- “Those with technical skills deemed of use for the war effort and the survival of the Russian state at large, are to be lured back with perks and protection. Those in exile who stood against the Kremlin and the war, fall into a special category—the Kremlin wants them to feel the crosshairs on their backs.”

- “Today, as Putin seeks to restore Russian greatness, ideas that had survived from the Soviet era are being abandoned. These include the notion of the friendship between the Russian and Ukrainian peoples, each of whom used to inhabit their own titular Soviet republic (this is one of the reasons Putin now criticizes the Soviet project).”

- “For the Kremlin, and arguably for many ordinary Russians, everything that was built by the Soviet state, and subsequently privatized, modernized and made fit for the market economy after the collapse of the USSR, is in fact ‘ours.’ In other words, it belongs to the state in whose name Putin and his acolytes claim to speak.”

- “Many Russians approve of the bombardment of Ukraine’s infrastructure because they consider the latter to be a gift to ungrateful Ukrainians, which is not being used for Russia’s benefit.”

- “The Kremlin and ordinary citizens of Russia tend to look at Ukraine and other former Soviet republics and forget that economic development would have happened there anyway—with or without them.”

- “What we are witnessing is the final transition from the Soviet ‘we’ to a new ‘us and them.’ Putin’s war on Ukraine is not only strengthening the emerging national identity of Ukrainians; it is also decisively changing the post-Soviet identity of many Russians.”

- “Even as Prigozhin appears to be receiving money and unusually heavy administrative support, formal power of any kind is not on offer. ... Prigozhin’s position is that of a kind of adventurous fellow-traveler, a useful contractor who only survives by generating results.”

- “That would explain Wagner’s dogged efforts to take Soledar and Bakhmut, two towns that are important but not critical to the Ukrainian defense of the Donetsk region: If both fall, the Ukrainian military will only roll back to the next formidable line of defense, again forcing Russians into head-on attacks of the kind that have distinguished Wagner so far.”

- “He’s a private businessman who is deeply dependent on his relationship with the government. It’s a very vulnerable position, so horizontal relationships with specific figures in power are critically important to him.”

- “In a Russia built around the state and designed to serve the state, his position as a non-state actor and as someone a little too unsavory for elite status even by late Putin-era standards is shakier than that of other invasion stalwarts. Like a hamster in a blood-smeared wheel, he has to keep running just to stay in place.”

Defense and aerospace:

- See section Military aspects of the Ukraine conflict and their impacts above.

Security, law-enforcement and justice:

- No significant developments.

III. Russia’s relations with other countries

Russia’s general foreign policy and relations with “far abroad” countries:

- “European leaders become more strategic about their goals for an end state after the war, they must address at least three questions.”

- “First, what kind of long-term security commitment to Ukraine should Europe signal now? … Second, without calling for regime change, are there rhetorical ways to rattle the Kremlin? … Third, what should be the EU’s policy toward Belarus and the wider region?”

- “Many European leaders do not seem to be developing strategies on even the most existential issues, such as Europe’s goals toward Russia. With Russia’s defeat and possible postwar turbulence coming increasingly into view, that urgently needs to change. Having launched a senseless, brutal, and unsuccessful war of aggression, Putin is unlikely to survive it in power. European leaders should prepare for this eventuality and start looking for a successor they can do business with. And primarily, they need to step up their efforts to help Ukraine win.”

“Untarnished by War: Why Russia's Soft Power Is So Resilient in Serbia,” Maxim Samorukov and Vuk Vuksanovic of the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 01.18.23.

- “Despised by some and admired by others, Russian soft power in Serbia appears to be ubiquitous and overshadows Moscow’s other ties to the Balkan country, including energy cooperation and shared opposition to Kosovo’s independence. Capitalizing on the historical grudge that many Serbs hold against the West, Russia enjoys enormous respect and popularity in Serbian society. But how sustainable is that popularity in the face of the Kremlin’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine? And what real limits does it impose on Serbian foreign policy?”

- “A public opinion poll conducted by the Open Society Foundation and Datapraxis in twenty-two countries in mid-2022 (to which the Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, or BCSP, had exclusive access) reveals that up until that point, the Kremlin’s invasion of Ukraine had changed surprisingly little in the attitudes of Serbs toward Russia. Serbia still remains a global pro-Russian outlier, even compared to Western-skeptic countries in the developing world. As many as 63 percent of polled Serbs held the West responsible for the outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war: significantly more than in all other polled countries, including Indonesia (50 percent), Turkey (43 percent), and India (34 percent). Later in the year, the BCSP conducted another poll to explore why Russia’s popularity among Serbs is so resilient.”

- “Still, Russia’s popularity in Serbia has its limits, and does not enable the Kremlin to simply manipulate the country’s policy decisions as it sees fit. To sustain its appeal, Moscow depends on the local pro-government propaganda machine, which is run by local elites and shapes the narrative according to their interests. The BCSP survey shows that 46 percent of polled Serbs believe that Serbia should stay neutral in the Russia-Ukraine war, confirming that a balancing act appears to be the least costly strategy for the Serbian government. Strong sympathy toward Russia notwithstanding, the Serbian public still believes that their country should steer clear of major international conflicts. But since it is vulnerable to pressure from Moscow, Serbia will remain reluctant to take any anti-Russian steps.”

- “The Russian invasion of Ukraine, inevitably and inexorably, will bear immense consequences for what once was a rule-based global order. Let me highlight the main four. First, the Ukraine war has sparked what the United Nations has called a complex emergency, where multiple crises, including food, energy and security, are unfolding concurrently and at a very rapid pace worldwide. Second, the invasion of Ukraine has further amplified the centrality of nuclear weapons in the 21st-century strategic landscape. Third, it has brought China, India and the Russian Federation’s ‘friendship’ into greater focus. Fourth, it has encouraged countries like Iran and North Korea to continue expanding their illicit military technology exports.”

- “All these factors will play a vital role in Asia. How the Asian countries will choose to manage them will very much determine the prospects for peace and security in the region and beyond.”

Ukraine:

- “Viktor Medvedchuk, for a long time a leading pro-Russia figure in Ukrainian politics, had until now been lying low since he turned up in Russia last year. A personal friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Ukrainian politician was detained trying to flee Ukraine last year, and was subsequently brought to Russia as part of a prisoner exchange. Now the publication of an article by Medvedchuk in the Russian newspaper Izvestia appears to herald his return to the public arena.”

- “On a practical level, the article calls for the establishment of some sort of center of emigration, a ‘government in exile,’ perhaps, that would speak on behalf of the Ukrainian ‘party of peace’ supposedly driven out of the country by President Zelensky. ‘A political movement of those who did not give in, who did not renounce their convictions even while fearing death or prison, who do not want to see their country become the setting for a geopolitical shoot-out,’ as Medvedchuk pompously puts it.”

- “If no ‘party of peace’ is emerging organically, Moscow appears prepared to create one artificially in order to hold peace talks with Medvedchuk instead of Zelensky: effectively, with itself. ... It suggests that the Kremlin is frantically looking for a way out of the dead end it has backed itself into in Ukraine.”

- “Still, Putin is remaining true to his strategy of launching several competing and incompatible political projects at the same time, and watching from outside the fray to see which will prove most successful. But there is also a more worrying subtext to Medvedchuk’s resurrection: that of possible preparations for a massive new offensive Russia is reported to be planning. It may be that the Kremlin hopes to send in its newly minted peacemaker on the baggage train of that offensive.”

“Ukrainian Victory Would Be Great for America,” Kyiv Mayor Vitali Klitschko, WSJ, 01.19.23. Clues from Ukrainian Views

- “With everything going on in the U.S., it's easy for Americans to wonder why they should do more. There are two reasons.”

- “The primary reason is that helping your friend during a brutal attack is the right thing to do. But American support isn't only a question of morals. America's investment in the liberation of Ukraine will protect other European nations against Russian aggression.”

- “The second reason is that helping Ukraine is good for America's economy, global leadership and businesses.”

- “What would continued American support entail?”

- “The U.S. has already created a 21st-century version of the old lend-lease program, which armed nations vital to U.S. interests during World War II. Expanding this program with congressional support would enable us to resolve this conflict sooner.”

- “We need even more advanced weaponry to take back lost territory.”

- “We also need to continue sustaining our people.”

- “When Russia fought dirty and put Ukraine on the ropes, America stood up for us, like an honest referee would. Every day, Ukrainians picking up the pieces in their liberated cities and fighting on the front lines are profoundly grateful for that. When the rebuilding begins, we won't forget who helped make it possible.”

Russia's other post-Soviet neighbors:

- “Despite Russia's decreasing power and China’s steady rise in Central Asia, Moscow remains a key economic and security actor in the region. Furthermore, it is still possible that it could further increase its presence in Central Asia as a result of to the Russia–Ukraine war. China has been expanding its economic relations and promoting infrastructural development at the expense of Russia. However, the evidence shows that Beijing currently has neither the tools to replace Russia nor the intention to be the dominant power in Central Asia. Moreover, Central Asian countries themselves prefer to follow a multi-vector policy. In this context, the increasing attention of the U.S. and recent engagement by the EU and European countries with Central Asia may also create challenges for China in expanding its influence in the region.”