In the Thick of It

A blog on the U.S.-Russia relationship

Russia’s Dwindling Middle Classes No Catalyst for Shift in Kremlin Foreign Policy

After years of rapid expansion during President Vladimir Putin’s first stint as president, Russia's middle class has dwindled in the years since his return to office in 2012. Confrontation with the west after the annexation of Crimea, the resulting sanctions and the Kremlin’s focus on macroeconomic stability at the expense of prosperity have entrenched a stagnation which has hit middle-earners hard. By one count, Russia’s middle class shrunk 20 percent during the economic crisis that followed.

But even as their economic decline coincided with Russia’s more aggressive foreign policy, there is little evidence that Russia’s current and former middle-classers connect their plight to the Kremlin’s conduct beyond its borders. There may be economic discontent at home, but Russia’s confrontational stance against the west remains popular, and calls to reverse years of economic inertia focus squarely on what the government can do on the domestic front—meaning Putin feels little pressure from Russia’s long-suffering middle classes to change course on the world stage.

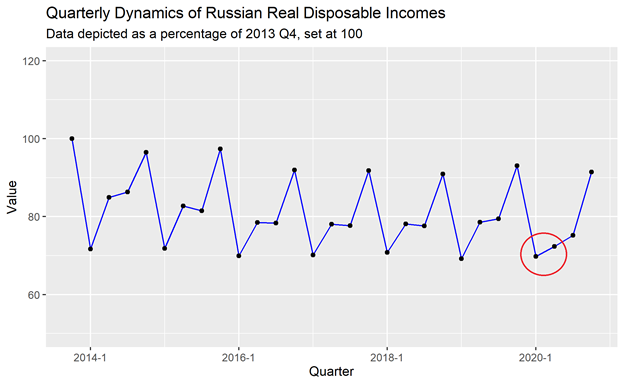

Such trends were only accentuated throughout the pandemic, as the government stuck to its stability-today, prosperity-tomorrow ethos. It rolled out only limited stimulus packages, refusing to open up its $180 billion sovereign wealth fund and ignoring the economic pain inflicted upon most businesses and households. So while Russia’s GDP had one of the world’s best performances last year, shrinking just 3 percent, Russians’ disposable incomes—a closely-tracked indicator of living standards—dropped 3.5 percent in real terms, a deeper hit than many other economies.

Russia’s middle classes were also largely forgotten. In the most detailed study of how the pandemic hit the middle class, Moscow’s Higher School of Economics (HSE) found almost 9 percent of those who fall into the category—with an income at least 25 percent above the regional median, a decent education and some level of responsibility at work—had lost their job. In total, the coronavirus recession caused another 6 percent to slip a class, HSE researchers estimated.

Putin promised little to reverse the hit in his annual state of the nation address Apr 21. “The main thing is to ensure the growth of real incomes of citizens,” Putin said. “We must restore real incomes and ensure further growth, to achieve tangible results in the fight against poverty,” he added, before unveiling a spending package of small cash handouts to families with children worth a miserly 0.2 percent of yearly GDP over the next two years.

But despite the hollowing out of Russia’s middle classes, there are a myriad of reasons why their malaise is likely to have no impact on Russia’s foreign policy.

First, Russia’s middle classes are already long-suffering. The costs of the pandemic itself were relatively shallow compared to what went before. Disposable incomes have fallen in five of the last seven years. Regression, not growth, has become the norm. Despite job losses and pay cuts, the decline of the middle class as a share of the population was not even particularly stark during the pandemic—a fall of 6 percent compared to 20 percent after the annexation of Crimea. Cushioned by white-collar jobs with work-from-home opportunities, the income hit was smaller than that experienced by society as a whole and, as Alexandra Burdyak, a senior researcher at RANEPA’s Institute of Social Analysis and Forecasting noted, they are probably the best positioned to quickly recover as the economy starts to pick back up.

None of this suggests the kind of irreversible or lifestyle-threatening economic hit that would be required to trigger enough discontent or outrage that might prompt a drastic change in policy from the Kremlin.

But even if some kind of economic breaking point had been reached, there are deeper reasons why we should not expect Russia’s middle classes to have any significant impact on Russia’s foreign policy.

For one, it is important to consider who we are actually talking about. Russia’s middle classes are starkly different from the entrepreneurs, executives and small business owners whom development models posit as drivers of change. With Russia’s economy overwhelmingly dominated by the state and private small enterprises making up just a fifth of GDP, analysts ranging from Carnegie’s Andrei Kolesnikov to Alfa Bank’s Natalia Orlova point out that Russia’s middle classes are an army of civil service bureaucrats and middle managers at state-controlled companies. They owe their family’s economic wellbeing to the sprawling state—under pressure as it may be, but still relatively stable and facing a slow-burning decline rather than a cliff-edge drop. They are not going to be agitating for the kind of wholesale changes that might necessitate some kind of foreign policy shift, such as easing confrontation with the west.

Generally, there is no clear causal relationship between Russian public opinion and foreign policy. Analysts tend to agree that the links are weaker than in a democracy (there is no fear of the possible electoral consequences of botched invasions or high military casualties, for instance). In a recent review on the “domestic determinants of Russia’s foreign policy,” former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul explicitly rejected the idea that public opinion is one of those “determinants.”

If analysts question the role broad public opinion has on Russia’s foreign policy, then after narrowing that population down to a group that makes up no more than a third of Russian society and which is disproportionately in the pay of the government, it becomes even harder to make the case that they, or their opinions, could be behind any shifts in Russia’s international conduct. This is a fact Russians themselves seem to be aware of given the low proportion who believe they can influence government policy.

Another important factor diminishing any potential role public opinion among the middle classes could exert is that the institutional gap between Russia’s domestic and foreign policy has grown wider since the annexation of Crimea.

In recent years the Kremlin has tried to create a clear divide between those who oversee foreign policy (Putin, the military, defense and security figures) and those who control domestic policy (Putin, the prime minister, government and business elites). That division has crystallized since the appointment of Mikhail Mishustin last year.

Even if Russian domestic decision makers know that Russia’s economic funk needs to be addressed—which they do—they also know that they cannot interfere with the remit of the foreign policy makers. There is little prospect, for instance, that Mishustin could win an argument for rolling back the counter-sanctions that make food more expensive for ordinary Russians, or that more friendly relations with the west could spur a surge of much-needed foreign investment and technology transfers, or to ditch the import substitution drive which requires billions of dollars in investment being diverted away from potentially more productive parts of the economy.

On an institutional level, Nikolai Petrov of Chatham House and Moscow’s HSE has pointed to the creation of de facto “parallel” governments within the state apparatus, such as new political commissions on international development and a beefed-up Security Council—separate frameworks to deal with foreign policy which have all but killed-off any influence the prime minister has over it.

Putin’s state of the nation address was another clue as to the separation of domestic and foreign policy in the eyes of those at the top. Amid huge tension with the west, a massive troop buildup in areas adjacent to Ukraine and persistent rumors of closer integration with Belarus, the president dedicated only a few generic words to foreign policy in his 80-minute speech, warning the west not to cross Russia’s “red lines.” It was enough rhetorical meat for the public and to keep the assembled parliamentarians and governors content without giving the impression that foreign policy was an area open to public debate.

This cognitive gap between foreign and domestic policy also exists within society, such that Russians in general do not consciously draw a connection between the country’s foreign policy choices and the economic costs they have brought.

Without that connection, there is no pressure for a change of course, particularly as foreign policy remains an important foundation of Putin’s legitimacy and support. The annexation of Crimea—the event which brought such heavy economic costs both in terms of external sanctions and the subsequent overhaul in Russia’s domestic economic policy the Kremlin believes was required to pay for it—remains wildly popular seven years on. One recent poll found only 7 percent of Russians have any negative feelings toward the annexation. Three in four believe the west would have imposed sanctions on Russia regardless of the Kremlin’s actions, with Crimea just a handy excuse.

There are few signs Russia’s middle classes want a change in foreign policy, and even fewer that they would be an influential agent in triggering it anytime soon. If Russia does decide to change course, it will likely have little to do with economic conditions on the homefront, or the fate of Russia’s long-suffering, slowly-dwindling middle classes.

Jake Cordell covers business and economics for The Moscow Times.

Photo by Don-vip shared under a Creative Commons license. The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author.