To Truly Pressure Russia’s Oligarchs, the West Should Target Their Wealth Managers

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Kyiv's Western allies have sanctioned numerous ultra-wealthy associates of Vladimir Putin, regarding them as enablers of Moscow's aggression. How to make these measures most effective has been a topic of debate, but one thing is clear: The global offshore system makes assets easy to hide and sanctions against them difficult to enforce. (A case in point was a superyacht linked to Uzbek-Russian billionaire Alisher Usmanov. Moored in Hamburg, it took German authorities more than a month to seize, shielded as it was by layers of company registrations in the Cayman Islands and Malta.)

But research conducted over the past year suggests that a more effective way to disrupt flows of money linked to Russian oligarchs subject to punitive measures by the U.S. and its allies may be to sanction the professional wealth managers who work for them, rather than targeting the oligarchs themselves. My Dartmouth College-based colleagues — Brooke Harrington, Feng Fu and Dan Rockmore — and I conducted network analyses to study the ties between oligarchs and their wealth managers in different countries, using leaks from offshore financial centers, including the Panama, Paradise and Pandora papers. We found that the Russian superrich would be especially vulnerable to the targeting of their professional intermediaries, as many of the former tend to trust the same small number of boutique wealth management firms. Moreover, these firms tend to be based in Europe, making them easier for Western governments to target. The U.S. Justice Department, together with European allies, has already begun using this approach.

Here are the three main findings that led to our conclusion.

Finding 1: Russia’s Superrich Rely on a Small Number of Wealth Managers

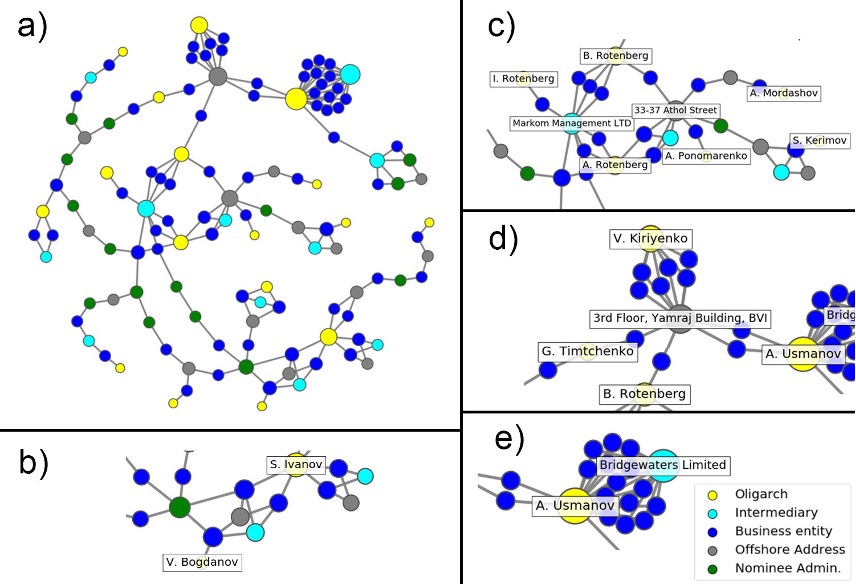

We focused our attention on the 44 oligarchs affected by the first wave of sanctions imposed in March 2022 in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; of those, 26 appeared in the above-mentioned data leaks, which have been provided by the International Consortium of Independent Journalists (ICIJ). In terms of networks, these 26 oligarchs can be connected through just 124 nodes out of 1.9 million. The figure below illustrates how oligarchs (yellow) trust the same wealth managers (cyan) to offshore their assets using offshore corporations (blue) and offshore addresses (gray). By zooming into local networks, we can recognize “motifs,” or patterns.

The first type of motif is predictable: the same wealth managers for members of the same family. For instance, according to multiple documents found in the Panama, Paradise and Pandora papers posted online by the ICIJ, Markom Management allegedly administered offshore corporations for brothers Boris and Arkady Rotenberg, who are behind several major infrastructure construction companies, in addition to owning other assets. A childhood friend and, reportedly, one-time judo sparring partner of Putin’s, Arkady Rotenberg was once dubbed “the king of state orders” for his lucrative government contracts, and spearheaded the building of the Crimean bridge that became a critical supply line to Russian troops during the current war (though it was damaged in October). In 2014 Arkady Rotenberg, who has denied some of the ICIJ claims, disputed owning shares in the company that built the bridge and sued the EU to lift sanctions against him. However, he lost that suit in 2016. More recently, Boris Rotenberg sued four European banks for refusing to service his accounts per the EU’s sanctions against him, starting in 2017. He lost that suit too.

A second motif is intermediaries shared by associates. According to the ICIJ and the Pandora Papers, for example, Boris Rotenberg is linked to an offshore address (where a shell company or trust is registered) that has also been connected with Usmanov and two other individuals, Vladimir Kiriyenko and Gennady Timchenko.[1] Kiriyenko is CEO of Russia’s largest social media platform, VK, and son of Sergei Kiriyenko, Putin’s first deputy chief of staff. Timchenko, ranked by Forbes this year as the seventh-wealthiest person in Russia,[2] has often been described as a close friend of Putin's since the early 1990s, when the latter granted him a license to export oil, according to The Guardian. Timchenko and his wife challenged European sanctions against them in the EU’s General Court in May, arguing that Timchenko's long acquaintance with Putin does not make him an ally in the war against Ukraine, Bloomberg reported. Usmanov — who has most recently claimed that it is his fame and fortune rather than links to Putin that made him a target for EU sanctions — and other Russian billionaires have filed similar lawsuits, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Finally, a third motif is that wealth management companies may repeatedly use the same strategies. The dark blue nodes in panel "e" above, based on the ICIJ database, show 14 offshore corporations set up by a single boutique management firm, Bridgewaters Limited. This firm is connected to a single oligarch, Usmanov, according to BBC. Both Bridgewaters and Usmanov have strongly denied the latter owns the former, according to BBC. In addition, Bridgewaters, according to a site called WealthBriefing, “has described claims it is at the core of a ‘Russian money network’ as ‘intentionally misleading.’”

Finding 2: Wealth Managers Are a Key Vulnerability in Financial Networks

These patterns are the threads that connect a complex system of secrecy, not just for individuals but at the group level: Oligarchs trust the same managers, and managers coordinate with each other, sometimes using the same addresses to register legal entities. This makes wealth managers a critical weakness in the network, particularly in autocratic regimes.

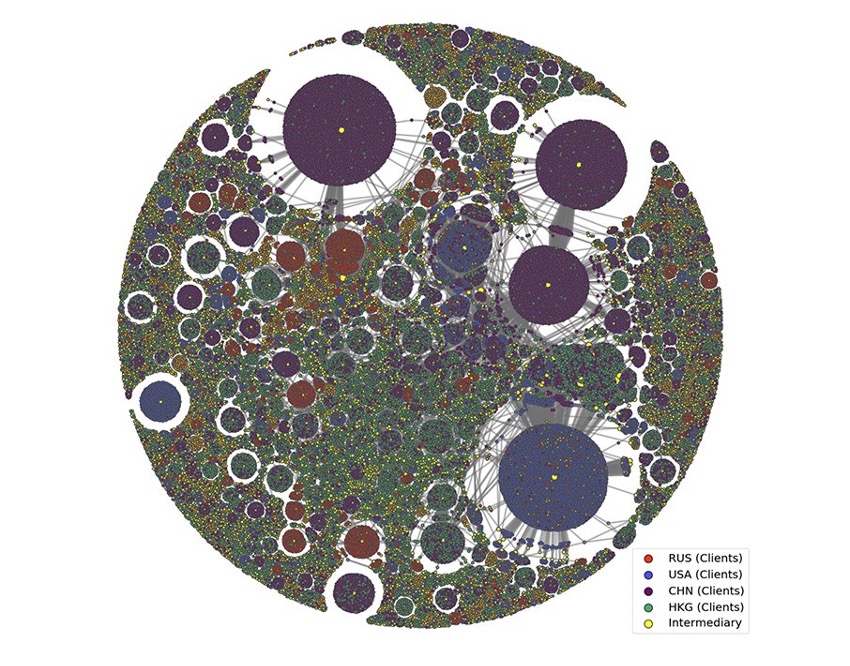

Typical of networks are inequalities in relations: Some managers are more “popular” (have more clients), and some may be brokers — not the most popular, but in control of the most critical pathways, such as holding the only relationship that connects two halves of a network. This is illustrated in the figure below, where yellow nodes are wealth managers, who are then connected to clients in Russia (red), the U.S. (blue), China (purple) and Hong Kong (green). The yellow nodes appear at the center of these clusters of clients, indicating that they are central to a local network.

Two findings highlight the vulnerability of the professional intermediaries guarding the secrets of the ultra-wealthy. First, in the offshore system, a small number of managers hold the majority of clients. This means that targeting the right nodes in these networks, which are generally resistant to attacks, can significantly disrupt the network. Second, we found that clients from autocratic countries like Russia are especially vulnerable to such disruptions. By running knock-out experiments — simulating what happens when key wealth managers are removed — we saw steep declines in the robustness of networks in Russia and China, meaning that there were very few connections with alternative wealth managers. This reaffirms that, while clients from autocratic states may be inclined to hide their assets in a diverse set of locations, they tend to trust the same managers at the group level.

Finding 3: Russians' Wealth Managers Tend to Be in Europe, Making Them Easier to Target

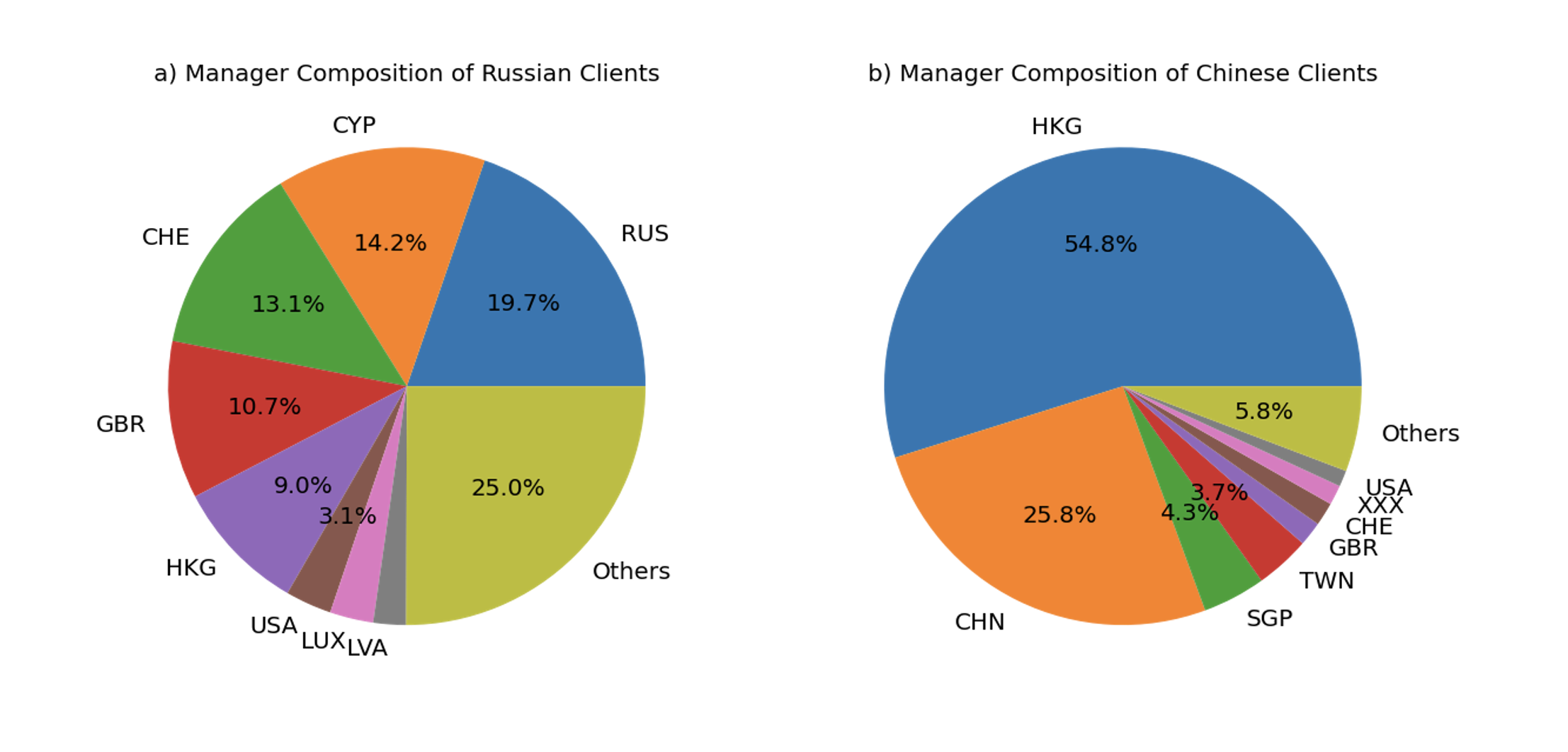

Although the super-wealthy from both Russia and China exhibit similar vulnerabilities, they diverge in the places where they source their managers. Russian clients draw from across Europe — with managers from Russia, Cyprus, Switzerland and Great Britain — plus from Hong Kong. In contrast, Chinese clients hire managers in Asia — more than 75% from Hong Kong and China, with another 8% from Singapore and Taiwan.

The locations of Russian clients' managers may improve the ability of Western countries to sanction intermediaries and, thus, to cut off oligarchs' access to their assets. Unlike the superrich in China, who can travel relatively unrestricted to Hong Kong within roughly the same administrative system, Russian oligarchs may find it comparatively difficult to coordinate with their Europe-based wealth managers. European governments can act more directly by sanctioning their own citizens, which is much simpler than exerting influence across borders. This practice is not unheard of: For instance, the EU banned a set of tax advisors and corporate-formation specialists in recent sanctions, though not wealth managers directly.

Such an approach can be effective as, under the offshore system, clients don’t actually own assets. Instead, managers come up with complex legal structures to hold these assets (such as Usmanov’s yacht) and to control them on their clients' behalf. By restricting coordination and targeting managers, governments can effectively limit the oligarchs' access to their wealth.

Conclusion

The efficacy of sanctions is debated, as Russia’s elites do not control Putin. However, there is evidence that sanctioning oligarchs has weakened public support for strongmen in autocratic regimes in the past — as seen, for example, with sanctions against Chilean elites during the Pinochet era. Indeed, early on we saw two Russian oligarchs call for an end to the war while one person – who was a multi-billionaire at the time — condemned it. These calls stirred hopes of a wedge between Putin and the country's elites, but these hopes are yet to materialize.

To some extent, Russia's oligarchs — though hardly a monolithic bunch — appear to be to Putin as the managers are to them: the supporting cast members who enable wealth and power. And, fortuitously, Europe-based intermediaries may be an accessible weak link for governments seeking to cut off some of the funds flowing to Moscow. Proactively finding the managers of those members of Russia's superrich who are most worth targeting may be a direct way of undercutting businesses' support for Putin, in our view.

Footnotes:

[1] The address, 3rd Floor, Yamraj Building, Market Square, P.O. Box 3175 Road Town, Tortola British Virgin Islands, has been linked to Pegasus Participation Limited, of which, according to the ICIJ, Boris Rotenberg is the ultimate beneficial owner; LTS Holding Limited, of which Timchenko is the former director, according to the ICIJ; and Morgoth Finance Ltd., a since-dissolved entity of which Kiriyenko was the ultimate beneficial owner, according to the ICIJ.

[2] For three of the billionaires deemed wealthier than Timchenko in the 2023 Forbes rating, family-owned assets were also counted.

Author

Ho-Chun Herbert Chang

Ho-Chun Herbert Chang is an incoming assistant professor of quantitative social science at Dartmouth College; he studies politics and social networks.

Ho-Chun Herbert Chang

Ho-Chun Herbert Chang is an incoming assistant professor of quantitative social science at Dartmouth College; he studies politics and social networks.

Opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, unless otherwise stated.

Photo by svklimkin, shared via Pixabay's free-for-use content license.