For Putin, Winning is Not Everything in Russia’s Presidential Election

Vladimir Putin is now a wartime president. The raging conflict in Ukraine—of uncertain outcome, no matter what the Kremlin boasts of coming victory—will provide the backdrop to the March 2024 presidential election. Fittingly, Putin announced his decision to seek reelection at a military awards ceremony at the urging of the speaker of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic parliament in what the Kremlin said was a “spontaneous” remark. It most certainly was not; Putin takes great care to avoid the appearance of grasping for power, but how could he resist the pleas of the people to carry on?

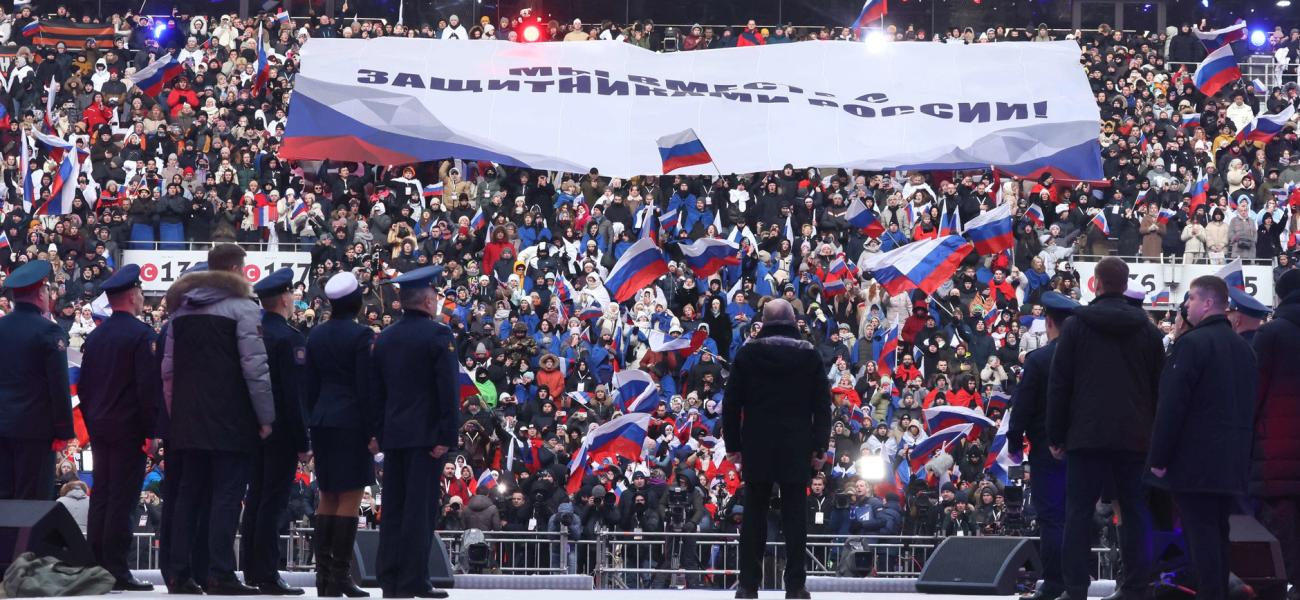

This essentially uncontested election is not an empty ritual, by any means. It cannot be foregone to save money for other purposes, as some Russian officials have suggested. Rather, it is meant to showcase Putin’s mastery of the political system, and therefore his legitimacy; by extension, it will serve as a referendum on the war itself. As in the past, the Kremlin will set targets for voter turnout and Putin’s share of the vote. It will then be challenged to energize regional officials, who conduct the election, and other public figures to meet those targets with minimal fraud. That would demonstrate the elite’s loyalty and mobilization skills, as well as the people’s acquiescence, if not active support. The smoother the operation, the less the fraud, the better for Putin’s authority.

To that end, the campaign that will now unfold until the election in mid-March will be designed to generate enthusiasm for Putin’s candidacy by highlighting the successes of the recent past. If it follows the pattern of past elections, it will also alert the elites and the people alike to tasks ahead. Two interrelated themes are certain to figure large: the military conflict in Ukraine and the larger hybrid war against the U.S.-led “collective West,” in which it is embedded.

Current conditions give the Kremlin much material to work with in promoting what has long been its story of Russian resilience, Ukrainian deficiencies and Western irresolution. Contrary to widespread expectations in the months after Russia’s full-scale invasion, Western sanctions have not crippled the Russian economy. It suffered only a small decline in 2022 and, the Kremlin projects, will grow 3-4% this year as Russia ramps up military production. With ingenuity and assistance from shadowy operators, Russia has managed to circumvent the West’s $60 cap on its oil exports. More oil revenue is now flowing into state coffers to finance military operations than before the conflict began. The decision to put the economy on a war footing has ensured the continuing flow of weaponry and shells to the front, while pushing the economy toward full employment.

Meanwhile, on the battlefield, Russia has beaten back Ukraine’s much ballyhooed counteroffensive. Although Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky denies it, Ukraine’s military chief, Valery Zaluzhny, admits that the conflict is now stalemated. In the wake of this failure, infighting in the Ukrainian leadership has broken out in public, shattering the facade of national unity that had coalesced in the face of Russian aggression. The lack of spectacular battlefield successes, such as the defense of Kyiv and the liberation of Kharkiv oblast and the city of Kherson in the first year of the war, has sparked a mounting debate in the West, especially in the United States, about the wisdom of continuing military and financial support for Ukraine. The Biden administration’s request for some $60 billion in further assistance has been held up in Congress with no early resolution in sight. Debate has also sharpened over whether it is now time for Ukraine’s Western backers to press for a ceasefire and a negotiated settlement, which in effect is a call for a peace deal that Kyiv has so far categorically rejected.

We can be sure that the Kremlin will use this state of affairs to project confidence that Russia is making steady progress toward achieving its goals in Ukraine, as Putin did during his annual year-end press conference. We can be equally sure that it will avoid all mention of the staggering cost—the U.S. intelligence community estimates that Russia has suffered some 315,000 dead and wounded during the conflict, close to 90% of the initial invasion force. In the run-up to the election, the Kremlin will want to dispel any rumors of a general mobilization, fearing the popular discontent such a step could spark—even a partial mobilization last fall led hundreds of thousands of young Russian men to flee the country to avoid conscription. It will want to maintain the illusion that the “special military operation” is not a war that will demand genuine sacrifices from the vast majority of the Russian population. Not surprisingly, during his press conference, Putin flatly stated that there would be no need for a mobilization as hundreds of thousands were already volunteering to go to the front.

Even if it believes victory in Ukraine is approaching, the Kremlin will still want to make sure Russians understand that the West’s hybrid war against them will continue unabated. Unity and vigilance will remain the order of the day. Patriotic rhetoric and displays will abound, especially with reference to Russia’s triumph over Nazi Germany. At the same time, we can expect the Kremlin to continue to rail, and take practical steps, against the propagation of what it considers alien and immoral Western values, especially LGBTQ rights, designed to sap the country’s vitality. The recent banning of the “international LGBT public movement” as an extremist organization will only incentivize local authorities to crack down on what they consider to be deviant behavior. On other matters, the criminalization of dissent will continue apace, including, in particular, any deviation from the official Kremlin line on the war in Ukraine.

In the end, the Kremlin will most likely achieve its electoral goals, reaffirming Putin’s vast political authority. Many officials well understand that the Kremlin’s portrayal of the state of affairs is far too rosy, but few will be willing to push back—the personal costs are simply too great in the repressive political system Putin has built. Moreover, there are great rewards to be reaped for vigorously backing Putin as he shuffles cadres in the presidential administration and government in preparation for his next term. This is the way the system is supposed to work. Whether Putin can lead his country to the victory he seeks in his war in Ukraine and against the West is another matter.

Thomas Graham

Thomas Graham is a distinguished fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. He is a cofounder of Yale University’s Russian, East European and Eurasian studies program and sits on its faculty steering committee. He is also a research fellow at Yale’s MacMillan Center. His latest book is "Getting Russia Right."

Opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author, unless otherwise stated. Photo by Kremlin.ru shared under a CC BY 4.0 license.